As frontline defenders for water protection in Pittsburgh and Southwestern Pennsylvania, staff of Three Rivers Waterkeeper patrol and monitor for pollution in our waterways by using high quality monitoring and sampling technologies to collect water samples. Our work contributes to the enormous efforts by watershed organizations to monitor water quality data in our region.

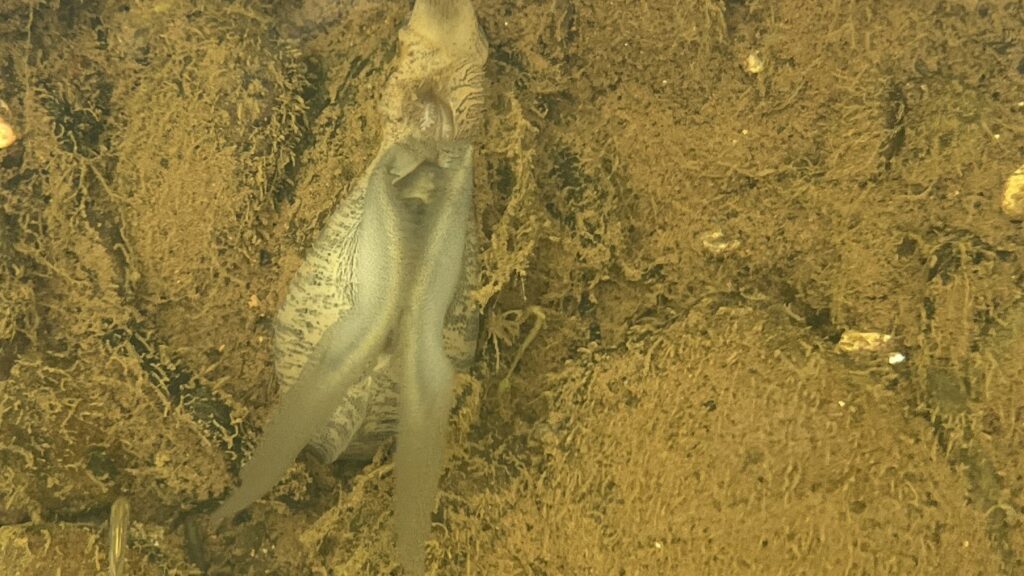

Wildlife observations occur so regularly in our work that the thought experiment about where best to place and monitor a biocube creates a dilemma. Over the modern history of our region, mass industrialization polluted our waterways, and our rivers became devoid of aquatic life. Fortunately, with the implementation of the 1972 Clean Water Act and subsequent clean water laws at the local, state, and federal levels, community organizations have been able to hold polluters accountable. As a result, we have seen wildlife come back to our rivers – including our national bird, the Bald Eagle. On or along the Allegheny River alone, the US Forest Service has documented rich species diversity, including over 50 mammals, 200 birds, 25 amphibians, 20 reptiles, 80 fishes, and 25 freshwater mussels.

We settled on a type of location rather than a specific one, the deltas formed by local tributary streams as the enter one of the three rivers referenced in our organization’s name. During the cycle of a full year on one of these patches of water-shaped land, a biocube might be fully submerged during some weeks, and shaded by riparian vegetation during other times. A list of likely plants and animals found temporarily within the cube’s bounds might very well include:

Related Content

Naturally Pittsburgh: Big Rivers and Steep Wooded Slopes

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Three Rivers Waterkeeper; Carnegie Museum of Natural HistoryPublication date: December 13, 2023