Did you know jack-o’-lanterns were once carved from turnips? Ancient Celtic cultures were known to carve turnips and place embers inside to ward off evil spirits. That’s because Ireland didn’t have pumpkins. When immigrants brought over their carving tradition, Americans began carving jack-o’-lanterns from pumpkins. This gave us a bigger canvas to work with!

The Great Pumpkin Flood

Can you imagine Halloween season without pumpkins? More than 200 years ago, eastern Pennsylvania experienced heavy rain causing the Susquehanna River to flood. The flood waters were so strong they washed away entire pumpkin crops. People were said to have seen pumpkins floating down the river, which was 5-10 feet higher due to the flooding. When the water began to subside, pumpkins were everywhere. This was known as The Great Pumpkin Flood of 1786.

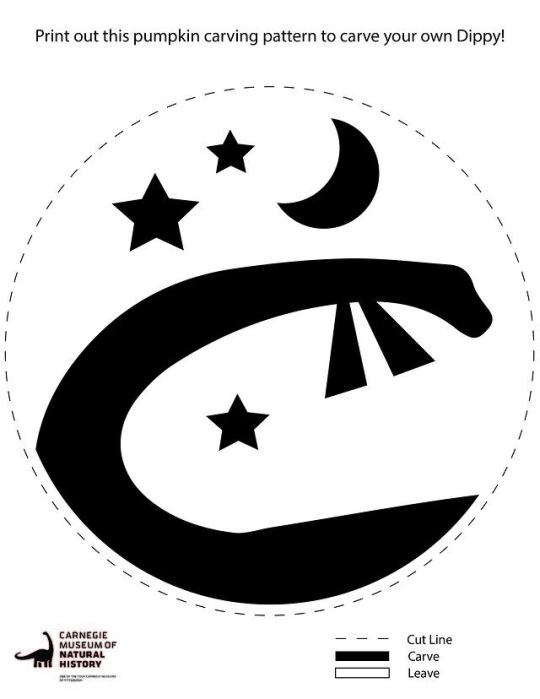

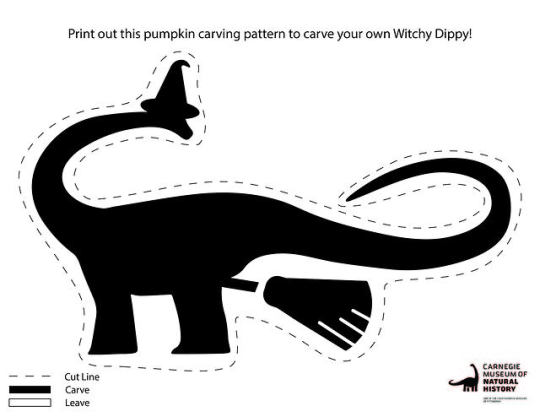

Dippy the Dinosaur Jack-o’-Lanterns

Our friend Dippy had so much fun with our last challenge, that they asked us to give you another! Do you think you can carve a Dippy jack-o’-lantern?

We have three pumpkin carving stencils for you to use that will bring Dippy to life, pumpkin style! You can choose to carve Dippy wearing a witch hat, Dippy in the night sky, or Dippy on a broom stick.

We’d love to see your jack-o’-lantern creations! Email them to nature360@carnegiemnh.org or tag Dippy on Twitter @dippy_the_dino.

Squash Dolls

Although pumpkins didn’t serve a large purpose in home decor until we began carving them, squash was popular to the Hidatsa Indians. Little girls were known to use squash as dolls. They would bring them in from the field, picking the ones that were multicolored, so the dolls looked to be wearing clothing.

Try more fun activities in Nature Lab!