From wild to cultivated to invasive

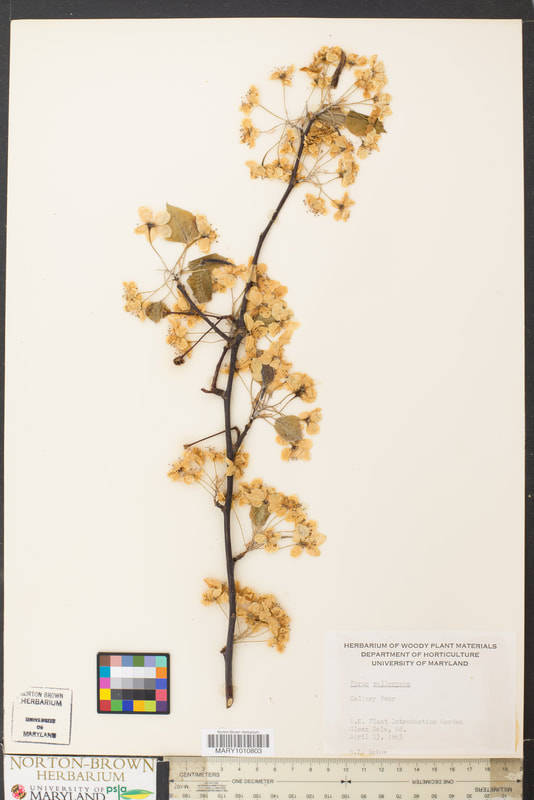

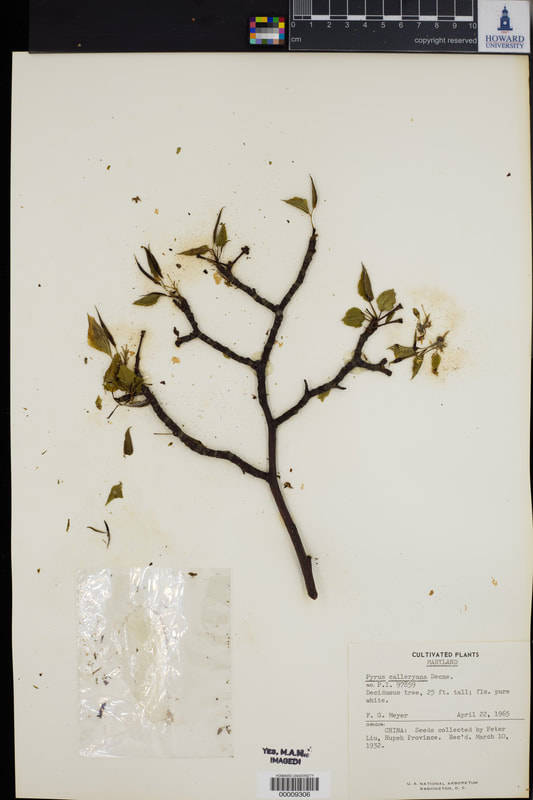

This specimen of Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana) was collected on October 11, 1979 by W.Z. Fang in Jiangsu, China. Callery pear is native to East Asia (China, Vietnam).

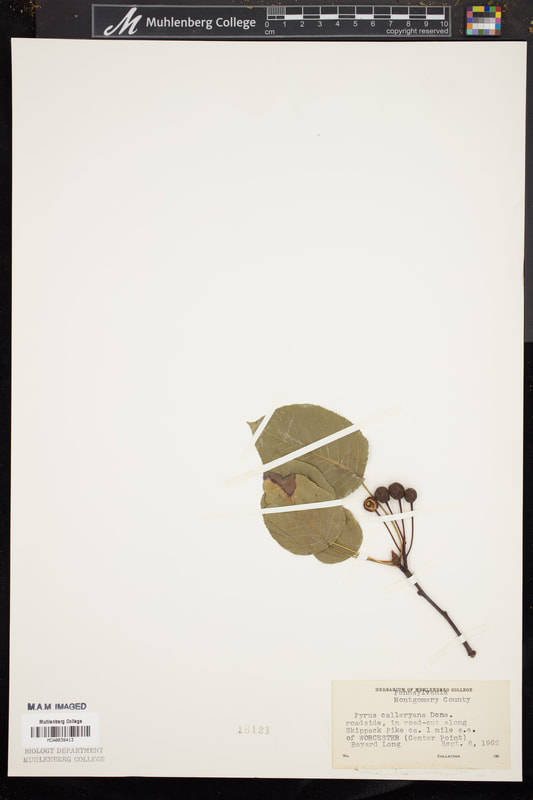

But…Callery pear can be found in the United States. It was (and is) widely planted as an ornamental landscape tree. Along streets, in residential yards, in parking lots – it was a prized plant for well-groomed anthropogenic landscapes. It uniformly grows in low resource conditions, explodes with many beautiful blossoms each spring, provides shade, and has a decent foliage display in the autumn. As many introduced plants go, it went from prized ornamental to an unwanted “invasive species,” spreading across the landscape and affecting the environment. It is now widely recognized invasive species in many states or closely watched as a species likely to become invasive. That said, beyond the legacy of over half a century of mass plantings across the country, it is still commonly planted and old and new cultivars are commercially available. USDA estimated over $23 million in sales in the US in 2009 alone.

How’d Callery pear get to the US? The story behind the introduction of Callery pear is a fascinating one. Like many of our cultivated plants, seeds were collected on special expeditions in search of plants useful to horticulture, agriculture, or just because. Pyrus calleryana was first introduced to the US in the early 1900s, though not for its attractive blossoms as you might expect. Instead, it was first introduced for its disease resistance. It was successfully used in horticulture as a root stock for European pear fruit production. At the time, European pears in the Pacific northwestern US were being hit hard, grafting to a Callery pear rootstock dramatically decreased crop losses to disease. Callery pear does not produce edible fruit.

The tree was widely planted starting in the 1960s, when it became commercially available and promoted by the nursery industry as a hardy ornamental tree. Before that, it was planted by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) for testing at Plant Introduction Stations in Corvallis, Oregon, and Glenn Dale, Maryland. One of these Maryland planted trees was targeted for its special traits and became the source of the hugely popular ‘Bradford’ cultivar (“Bradford pear”). In 1952, one tree was used to graft to rootstock, a plant propagation method making all plants genetically identical. Other cultivars have since been commercialized, but ‘Bradford’ were/are exceptionally popular. Though intended to be sterile (non-reproducing), it turned out the trees were capable of setting viable seed. The cultivars themselves are not invasive, but because multiple cultivars exist, together they can cross-pollinate to become invasive.

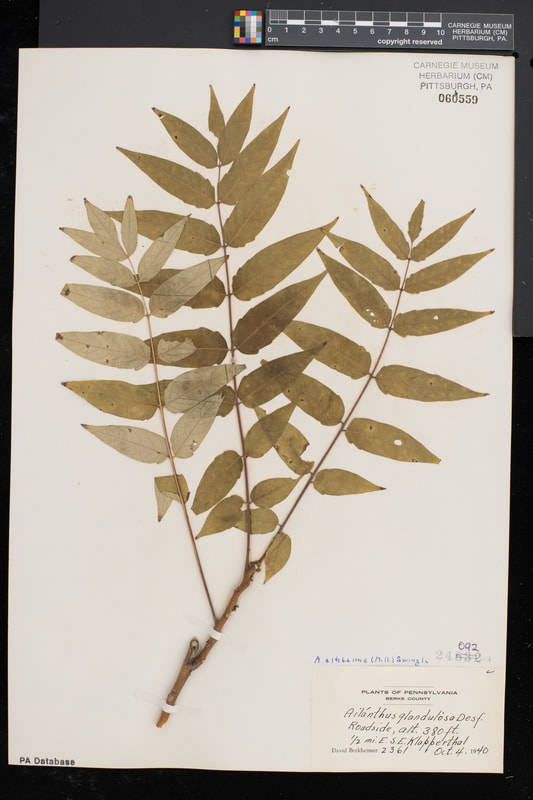

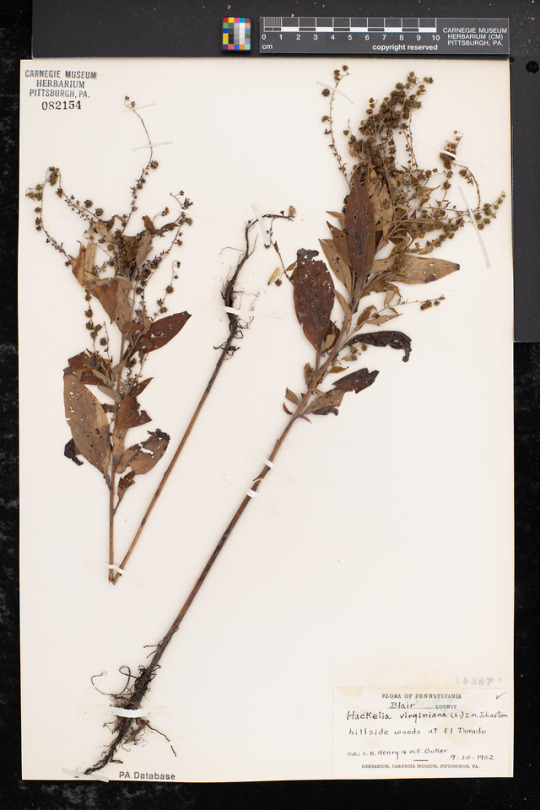

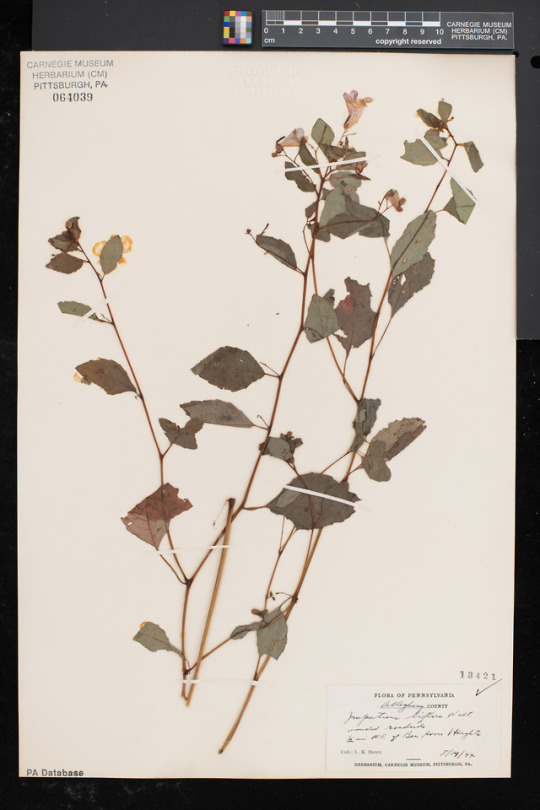

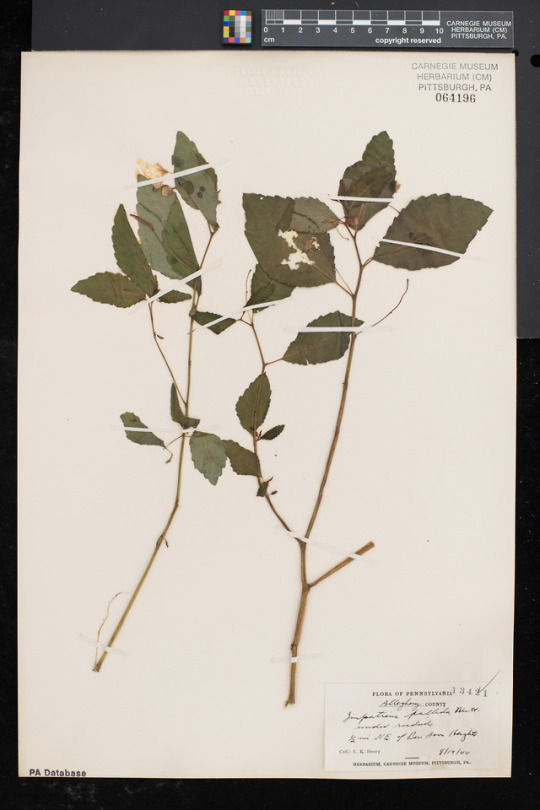

Herbarium specimens have been critical to understanding the spread of this species. In a 2005 study, Dr. Michael Vincent (Miami University in Ohio) found that 50% of all specimens examined over the range of 39 years were collected between 2000-2003. Though some specimens were collected in the 1960s in natural areas, it became widely “escaped” from cultivation in many natural areas in the 1990s.

You may have noticed that most of our specimen images to date are those collected in Pennsylvania and surrounding states. That’s because these specimens are being digitized as part of a multi-institutional project, the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project, with the overarching goal to mobilize herbarium specimens across the region to understand the effects of urbanization on plant life. However, this project is a step towards digitizing the entire Carnegie Museum Herbarium. The herbarium is worldwide in scope, and specimens in the Mid-Atlantic region account for only 35% of the 540,000 specimens.

As more specimens become digitized as part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project, we’ll have a more complete understanding of the introduction and spread of Callery pear in the region.

Herbarium specimens are collected in the native range too! We’ll be able to compare specimens collected in the invaded range to those in its native China. The use of cultivated specimens and those collected in the native range are underutilized but can provide critical information.

Many more specimens like this will be brought to light through the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project.

Read more about this species introduction history in the popular press, published in the Washington Post last year, and in an excellent overview by Dr. Theresa Culley (University of Cinncinati) in Arnoldia and another in BioScience.

See all the Pyrus calleryana specimens being made available online from the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis project here: http://midatlanticherbaria.org/portal/collections/list.php?db=277%2C328%2C334%2C329%2C333%2C320%2C330%2C40%2C410%2C316%2C335%2C331%2C332%3B11&includecult=1&taxa=Pyrus+calleryana&usethes=1&taxontype=2

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They are in the midst of a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.