by Shelby Wyzykowski

What better way can you spend a quiet evening at home than by having a good old-fashioned movie night? You dim the lights, cozily snuggle up on your sofa with a bowl of hot, buttery popcorn, and pick out a movie that you’ve always wanted to see: the 1948 classic Unknown Island. Mindlessly munching away on your snacks, your eyes are glued to the screen as the story unfolds. You reach a key scene in the movie: a towering, T. rex-sized Ceratosaurus and an equally enormous Megatherium ground sloth are locked in mortal combat. And you think to yourself, “I’m pretty sure something like this never actually happened.” And you know what? Your prehistorically inclined instincts are correct.

From the time that the first dinosaur fossils were identified in the early 1800s, society has been fascinated by these “terrible lizards.” When, where, and how did they live? And why did they (except for their modern descendants, birds) die out so suddenly? We’ve always been hungry to find out more about the mysteries behind the dinosaurs’ existence. The public’s hunger for answers was first satisfied by newspapers, books, and scientific journals. But then a whole new, sensational medium was invented: motion pictures. And with its creation came a new, exciting way to explore the primeval world of these ancient creatures. But cinema is art, not science. And from the very beginning, scientific inaccuracies abounded. You might be surprised to learn that these filmic faux pas not only exist in movies from the early days of cinema. They pervade essentially every dinosaur movie that has ever been made.

One Million Years B.C.

Another film that can easily be identified as more fiction than fact is 1966’s One Million Years B.C. It tells the story of conflicts between members of two tribes of cave people as well as their dangerous dealings with a host of hostile dinosaurs (such as Allosaurus, Triceratops, and Ceratosaurus). However, neither modern-looking humans nor dinosaurs (again, except birds) existed one million years ago. In the case of dinosaurs, the movie was about 65 million years too late. Non-avian dinosaurs disappeared 66 million years ago during a mass extinction known as the K/Pg (which stands for “Cretaceous/Paleogene”) event. An asteroid measuring around six miles in diameter and traveling at an estimated speed of ten miles per second slammed into the Earth at what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico. The effects of this giant impact were so devastating that over 75% of the world’s species became extinct. But the dinosaurs’ misfortunes were a lucky break for Cretaceous Period mammals. They were able to gain a stronger foothold and flourish in the challenging and inhospitable post-impact environment.

Cut to approximately 65 million, 700 thousand years later, when modern-looking humans finally arrived on the chronological scene. Until recently, the oldest known fossils of our species, Homo sapiens, dated back to just 195,000 years ago (which is, in geological terms, akin to the blink of an eye). And for many years, these fossils have been widely accepted to be the oldest members of our species. But this theory was challenged in June of 2017 when paleoanthropologists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology reported that they had discovered what they thought may be the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens on a desert hillside at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. The 315,000-year-old fossils included skull bones that, when pieced together, indicated that these humans had faces that looked very much like ours, but their brains did differ. Being long and low, their brains did not have the distinctively round shape of those of present-day humans. This noticeable difference in brain shape has led some scientists to wonder: perhaps these people were just close relatives of Homo sapiens. On the other hand, maybe they could be near the root of the Homo sapien lineage, a sort of protomodern Homo sapien as opposed to the modern Homo sapien. One thing is for certain, the discovery at Jebel Irhoud reminds us that the story of human evolution is long and complex with many questions that are yet to be answered.

The Land Before Time

Another movie that misplaces its characters in the prehistoric timeline is 1988’s The Land Before Time. The stars of this animated motion picture are Littlefoot the Apatosaurus, Cera the Triceratops, Ducky the Saurolophus, Petrie the Pteranodon, and Spike the Stegosaurus. As their world is ravaged by constant earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, the hungry and scared young dinosaurs make a perilous journey to the lush and green Great Valley where they’ll reunite with their families and never want for food again. In their on-screen imagined story, these five make a great team. But, assuming that the movie is set at the very end of the Cretaceous (intense volcanic activity was a characteristic of this time), the quintet’s trip would have actually been just a solo trek. Ducky and Petrie’s species had become extinct several million years earlier, and Littlefoot and Spike would have lived way back in the Jurassic Period (201– 145 million years ago). Cera alone would have had to experience several harrowing encounters with the movie’s other latest Cretaceous creature, the ferocious and relentless Sharptooth, a Tyrannosaurus rex.

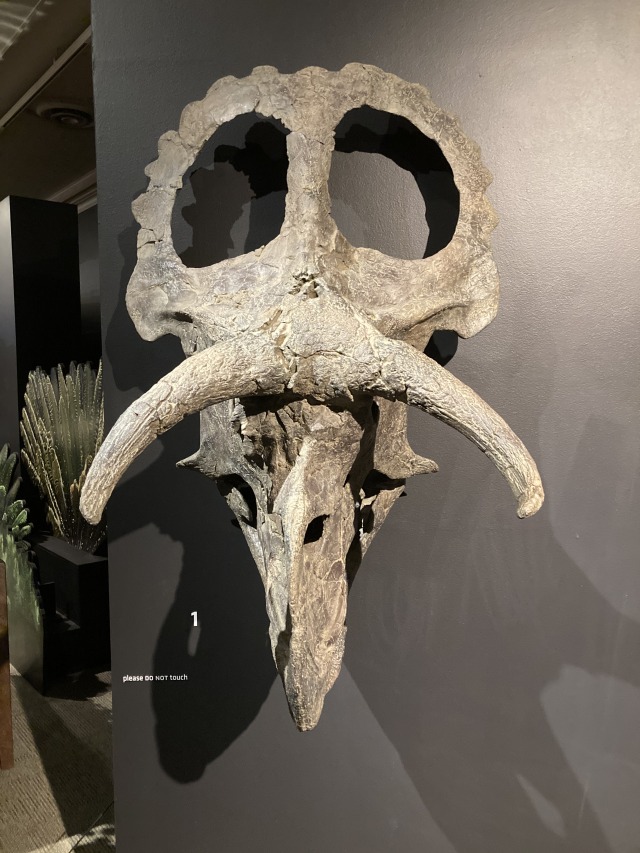

Speaking of Sharptooth, The Land Before Time’s animators made a scientifically accurate choice when they decided to draw him with a two-fingered hand, as opposed to the three fingers traditionally embraced by other movie makers. For 1933’s King Kong, the creators mistakenly modeled their T. rex after a scientifically outdated 1906 museum painting. Many other directors knowingly dismissed the science-backed evidence and used three digits because they thought this type of hand was more aesthetically pleasing. By the 1920s, paleontologists had already hypothesized that these predators were two-fingered because an earlier relative of Tyrannosaurus, Gorgosaurus, was known to have had only two functional digits. Scientists had to make an educated guess because the first T. rex (and many subsequent specimens) to be found had no hands preserved. It wasn’t until 1988 that it was officially confirmed that T. rex was two-fingered when the first specimen with an intact hand was discovered. Then, in 1997, Peck’s Rex, the first T. rex specimen with hands preserving a third metacarpal (hand bone), was unearthed. Paleontologists agree that, in life, the third metacarpal of Peck’s Rex would not have been part of a distinct, externally visible third finger, but instead would have been embedded in the flesh of the rest of the hand. But still, was this third hand segment vestigial, no longer serving any apparent purpose? Or could it have possibly been used as a buttressing structure, helping the two fully formed fingers to withstand forces and stresses on the hand? Peck’s Rex’s bones do display evidence that strongly supports arm use. You can ponder this paleo-puzzle yourself when you visit Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition, where you can see a life-sized cast of Peck’s Rex facing off with the holotype (= name-bearing) T. rex, which was the first specimen of the species to be recognized (by definition, the world’s first fossil of the world’s most famous dinosaur!).

Jurassic Park

One motion picture that did take artistic liberties with T. rex for the sake of suspense was 1993’s Jurassic Park. In one memorable, hair-raising scene, several of the movie’s stars are saved from becoming this dinosaur’s savory snack by standing completely still. According to the film’s paleontological protagonist, Dr. Alan Grant, the theropod can’t see humans if they don’t move. Does this theory have any credence, or was it just a clever plot device that made for a great movie moment? In 2006, the results of ongoing research at the University of Oregon were published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, providing a surprising answer. The study involved using perimetry (an ophthalmic technique used for measuring and assessing visual fields) and a scale model T. rex head to determine the creature’s binocular range (the area that could be viewed at the same time by both eyes). Generally speaking, the wider an animal’s binocular range, the better its depth perception and overall vision. It was determined that the binocular range of T. rex was 55 degrees, which is greater than that of a modern-day hawk! This theropod may have even had visual clarity up to 13 times greater than a person. That’s extremely impressive, considering an eagle only has up to 3.6 times the clarity of a human! Another study that examined the senses of T. rex determined that the dinosaur had unusually large olfactory bulbs (the areas of the brain dedicated to scent) that would have given it the ability to smell as well as a present-day vulture! So, in Jurassic Park, even if the eyes of T. rex had been blurred by the raindrops in this dark and stormy scene, its nose would have still homed-in on Dr. Grant and the others, providing the predator with some tasty midnight treats.

Now, it may seem that this blog post might be a bit critical of dinosaur movies. But, truly, I appreciate them just as much as the next filmophile. They do a magnificent job of providing all of us with some pretty thrilling, edge-of-your-seat entertainment. But, somewhere along the way, their purpose has serendipitously become twofold. They have also inspired some of us to pursue paleontology as a lifelong career. So, in a way, dinosaur movies have been of immense benefit to both the cinematic and scientific worlds. And for that great service, they all deserve a huge round of applause.

Shelby Wyzykowski is a Gallery Experience Presenter in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Super Science Saturday: Jurassic Day (July 31, 2021)

What Did Dinosaurs Sound Like?

Diplodocus carnegii (Dippy) – Dinosaur Spotlight (Video)

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wyzykowski, ShelbyPublication date: July 29, 2021