by Patrick McShea

Hispanic Heritage Month creates an opportunity to consider how we share some forms of winged wildlife with Spanish-speaking regions far to our south. At this time of year, many bird species that are widely considered to be Pennsylvania residents are in the process of a long seasonal migration to warmer climates.

This migratory behavior pattern, established long ago in each species’ evolutionary history, occurs every fall, and reverses with northward movement in the spring. Just as we might consider the wild creatures who spend summers with us to be ours, the people at the Caribbean, Central American, and South American locations where these creatures pass the months of our Pennsylvania winter might consider the winged seasonal visitors to be theirs.

An informal walk to locate three migratory birds and one migratory butterfly among the exhibition halls of Carnegie Museum of Natural History is a good way build background knowledge about wildlife sharing. Recognition of such sharing is a step toward understanding more about other cultures.

Stop #1: Scarlet Tanager (known in Spanish as Piranga Escarlata)

Within the interactive space known as Discovery Basecamp, the Scarlet Tanager’s bright plumage should be easy to locate among other encased bird taxidermy mounts. As the species account in All About Birds states: Male Scarlet Tanagers are among the most blindingly gorgeous birds in an eastern forest in summer, with blood-red bodies set off by jet-black wings and tail.

Recent population studies, which included lots of community science generated data, indicate that Pennsylvania supports more breeding pairs of Scarlet Tanagers than any other state.

Because this species feeds and nests high in the tree canopy, learning to recognize their distinctive song is a good way to spot one. If this technique enables you to spot a bright red male or yellowish-green female, remember that for some months of the year the bird you’re watching might reside in forests as far away as Bolivia.

Stop #2: Monarch Butterfly (known in Spanish as Mariposa Monarca)

The familiar orange and black monarch butterfly flitting across your neighborhood in the fall might be embarking on an incredible journey from field edges in Pennsylvania to the cool and relatively moist habitat of oyamel fir forests in Mexico’s Sierra Madre Mountains. The seasonal movement of monarchs across the North American continent is one of the longest migrations of any insect. In full cycle, however, it differs from bird migration in reliance upon multiple generations.

The long southbound fall journey is completed by some of the individual butterflies who embark upon it. These butterflies initiate northward migration in the spring, but no individuals complete the roundtrip journey. Northbound female monarchs lay eggs for a subsequent generation to continue the migration to our region.

Female monarchs lay eggs on the leaves of milkweed plants, the food source for the caterpillars that hatch within days. The display in the Hall of Botany depicts two of the eleven species of milkweed native to Pennsylvania.

Stop #3: Chimney Swift (known in Spanish as Vencejo de Chimenea)

In urban, suburban, and even rural areas of southwestern Pennsylvania, the high-pitched twittering cries of circling Chimney Swifts create a soundtrack for summer days. The birds’ aerial maneuvers are a mix of rapid wing beats and dynamic glides, and much of the action relates to feeding. Chimney Swifts eat on the wing, using their unusually large mouths to capture up to 5,000 flying insects per day.

When the birds disappear from our skies in the fall, they undertake a journey of thousands of miles to the upper reaches of South America’s Amazon Basin, in Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil, where they spend much of the winter.

In our region, the species roosted and nested in hollow trees before the proliferation of chimneys that accompanied the European colonization of North America. The species is so physically adapted to life on the wing that it is unable to perch upright for long. Note the protruding tail feather shafts on the taxidermy mount. These stiff braces help the bird to hold resting positions against the interior vertical surfaces of chimneys or hollow trees.

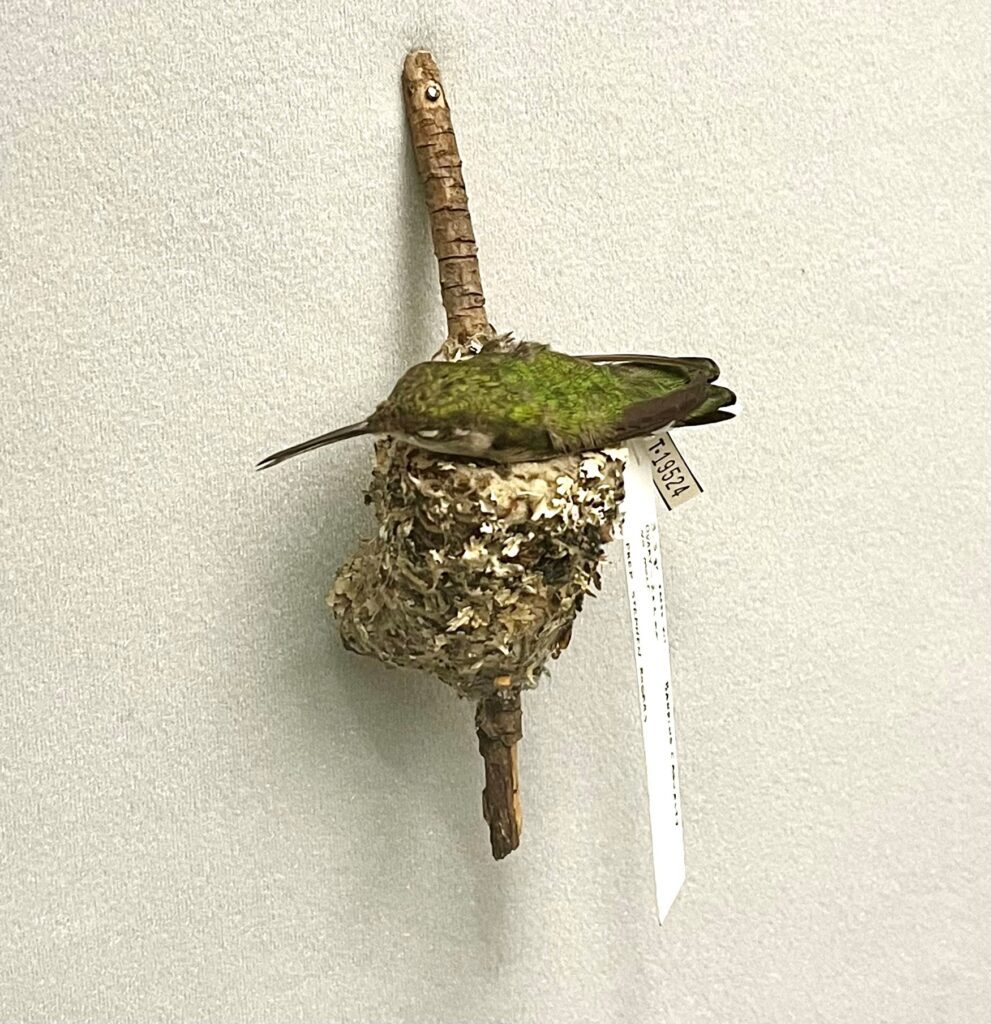

Stop #4: Ruby-throated Hummingbird (known in Spanish as Colibri Gorjirrubi)

Although there is a Ruby-throated Hummingbird taxidermy mount immediately adjacent to the Chimney Swift mount, the specimen pictured above is located elsewhere in Bird Hall. This female bird, displayed on a nest, is in “study skin” form. Study skins lack the glass eyes and life-like poses of taxidermy mounts, and their uniform flatness facilitates both storage and scientific study. Most of the 190,000 birds in the museum’s scientific collection (including many from Spanish-speaking regions of the world) are in study skin form.

From May through December, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds attract our attention when they visit some of the flowers we tend, or feeders placed specifically to attract the birds. The species’ diet also includes mosquitoes, gnats, fruit flies, small bees, and spiders. On their breeding grounds, six to ten days of construction work by the female bird results in an inch-deep, two-inch diameter, branch-top nest lined with plant down, held together with spider silk, and for concealment purposes, shingled with lichen chips.

Their annual southward migration includes passage over or around the Gulf of Mexico to reach wintering grounds that stretch southward from Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula to Costa Rica.

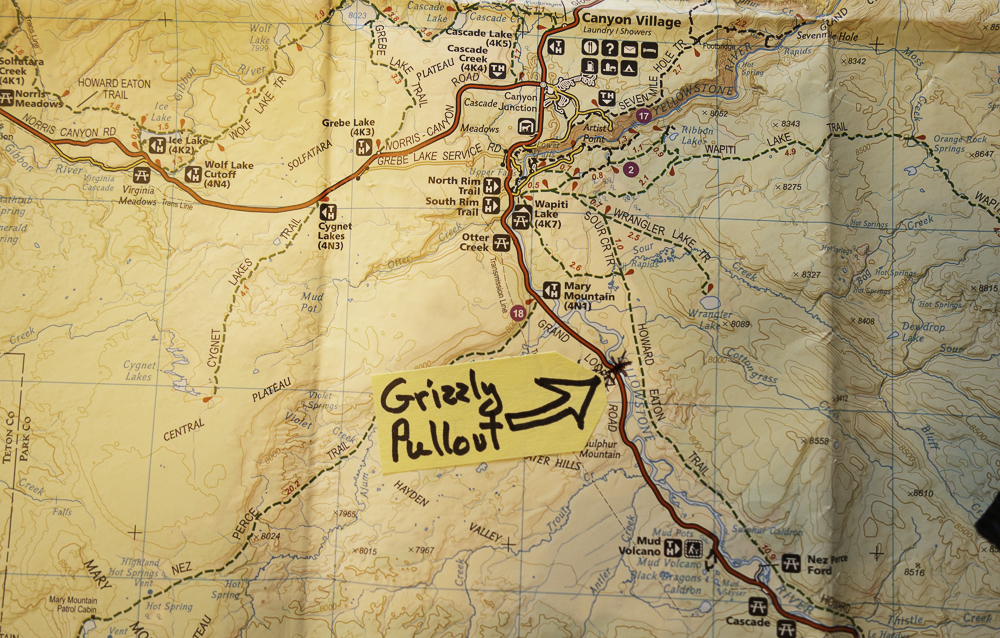

Maps indicating breeding ranges, wintering grounds, and the migration corridors between those locations are critically important tools for understanding the movements of migratory wildlife within and between continents. Much of the information about the birds profiled in this activity comes from species accounts of All About Birds, an encyclopedic online resource maintained by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. In each account, a species’ continental-scale migration movements are depicted on color-coded maps.

Another notable facet of the website maintained by Cornell Lab of Ornithology is the availability of education materials in Spanish.

Patrick McShea is an Educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: October 6, 2023

Share this post!

Location key:

Stop #1: Discovery Basecamp

Stop #2: Hall of Botany

Stop #3: Bird Hall

Stop #4: Bird Hall