by Patrick McShea

The Twelve Days of Christmas

When a traditional song about Christmas gifts reaches young ears, the centuries-old lyrics naturally prompt questions. If you’ve been on the receiving end of inquiries such as “What’s a partridge?”, a museum visit can provide identity information for the abundance of birds mentioned in the “Twelve Days of Christmas.”

Although the birds cited below aren’t precise matches for European species of the song, locating these feathered references can renew your own appreciation for what might be an overly familiar tune.

Inspiration and informational reference for the re-interpretation of several exhibits comes from a 2018 American Ornithological Society blog post by Bob Montgomerie, an evolutionary biologist at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario. Dr. Montgomerie’s post is titled “Three French Hens.”

A Partridge in a Pear Tree

In Pennsylvania, the Ruffed Grouse has reigned as state bird since 1931. The species’ collective value to Pennsylvania residents includes the gamebird’s historic importance as a food source and its current role as the focus of much upland sport hunting. The bird referenced in the song might well have been the Red-legged Partridge, a European species known to science as Alectoris rufa, however, the Ruffed Grouse is a decent substitute because the bird, which is known to perch in trees occasionally, is routinely called “partridge” in Maine and other portions of the northeast.

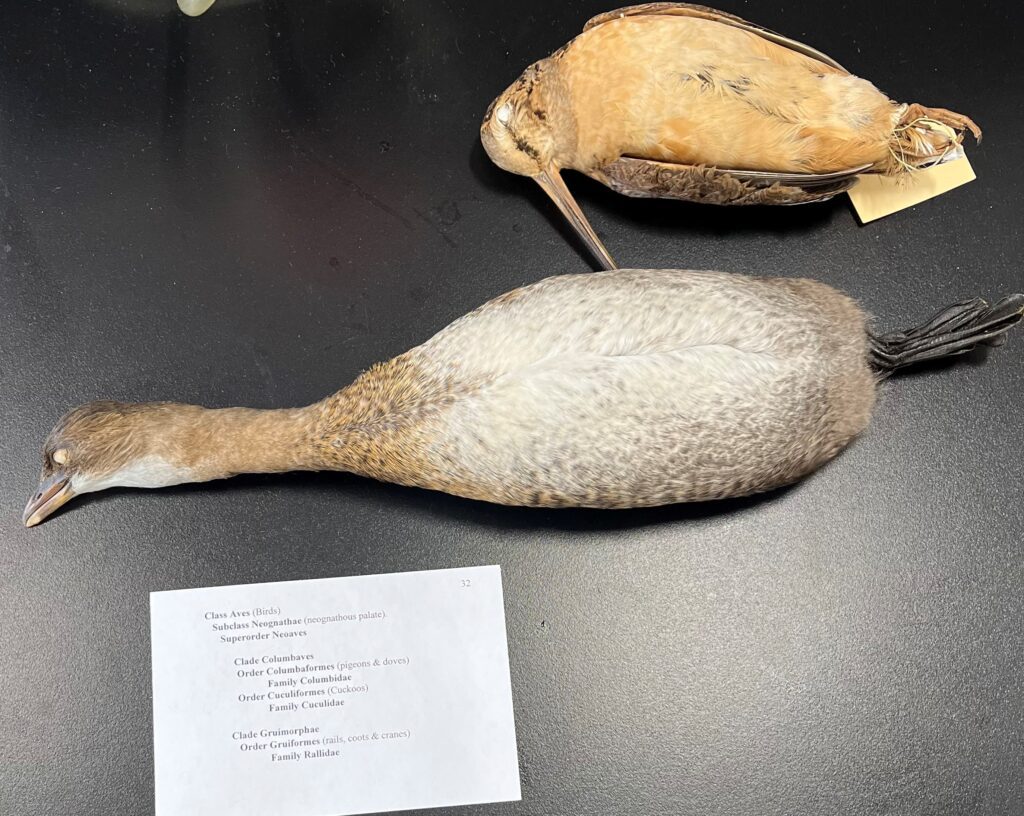

Two Turtle Doves

The European Turtle Dove, Streptopelia turtur, is a member of the bird family of doves and pigeons known as Columbidae. Generally, the smaller species in the family are called doves, and the larger species ae called pigeons. The Passenger Pigeon is the most notable family member on display at the museum.

Passenger Pigeons were once so abundant in eastern North America that flocks darkened the skies for hours when the birds migrated to access seasonal feeding areas and nesting sites.

Sustainable use of the birds by humans did not continue into the 19th Century. By mid-century, Passenger Pigeons became an unregulated commodity in the rapidly expanding American economy, with the country’s growing railroad network and parallel telegraph system providing unprecedented means for sharing word of flock locations, transporting hunters to those sites, and shipping harvested birds to distant markets.

Three French Hens

The song reference is to a specific breed of domestic chicken. There are no domestic chickens on display in the museum, but the species is usually well-represented in the food selections offered within the building’s dining areas. Some scientists have speculated that our current reliance on domestic chickens as a global source of protein for human consumption might someday leave deposits of chicken bones as an identifying mark of the Anthropocene, a proposed name for the current geologic age, viewed as the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment.

Four Calling Birds

If we use the cited author’s research finding, (The original ‘colly bird’ was the Eurasian Blackbird (Turdus merula) as ‘colly’ meant ‘black’ as in ‘coaly,’ and is why border collies bear that name.) the Northern Ravens in an Art of the Diorama display can fill this slot. Another candidate is the American Crow, a species frequently observed passing over the museum building at dusk during winter evenings, heading to local roosts in scattered flocks that number in the thousands. Ornithologists explain the birds’ collective behavior as taking advantage of a “heat island effect,” a base temperature in a city that is five or more degrees warmer than the surrounding countryside.

Five Golden Rings

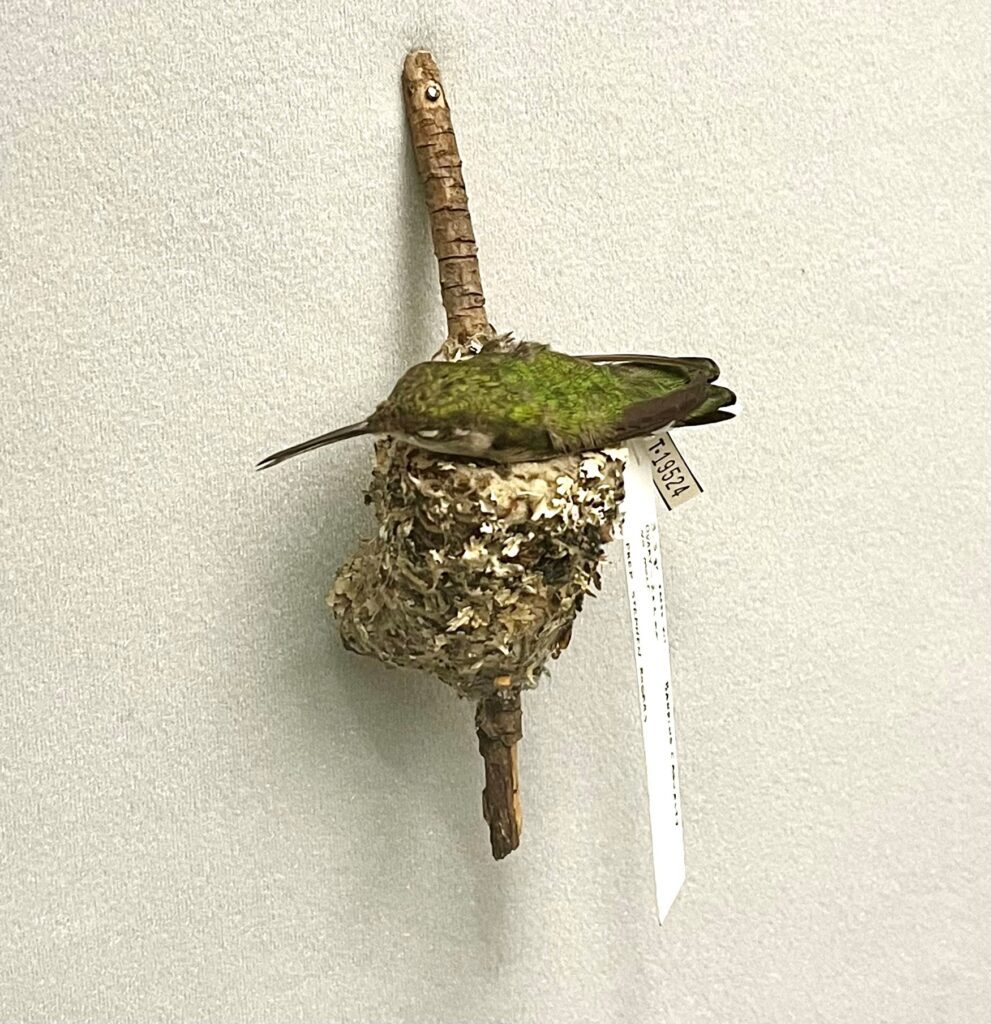

“Five golden rings” might also have a bird connection. Dr. Montgomerie’s post mentions both Gold Finches and Ring-necked Pheasants as possible references, but the museum’s long history of bird banding at Powdermill Nature Reserve, the location of Powdermill Avian Research Center (PARC), allows a different approach. Bird banding is a research practice that involves capturing wild birds, marking them with numbered leg bands, and releasing them unharmed. In some parts of the world this centuries’ old effort to verify bird movements through recovered birds is called “ringing.” It is admittedly a stretch between gold rings and aluminum bands, but for a close look at the latter, check the tabletops in Discovery Basecamp for an encased taxidermy mount of a Gray Catbird bearing one of the lightweight markers on its right leg.

Six Geese A-laying

Although the lyric refers to a domestic variety, a scene focused on an enormous gathering of a wild species in The Art of the Diorama demonstrates the eventual outcome of “geese a-laying” – more geese. Here Blue Geese, a variety of Snow Geese with dark plumage, are shown gathering near James Bay in preparation for a continent-crossing migration. The dark-headed geese in the foreground are young of the year, the most recent product of “Snow Geese a-laying.”

Seven Swans A-swimming

A lone Tundra Swan watches over Discovery Basecamp from a high perch. Thousands of these birds fly, rather than swim, across Pennsylvania spring and fall during seasonal migrations between Arctic nesting grounds and wintering territory along the Chesapeake Bay. Their fall passage over western Pennsylvania, announced by flock calls some people describe as “like the baying of distant hounds,” generally occurs between mid-November and early December.

Patrick McShea is an Educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Collected On Christmas Eve 1883: Mistletoe

2022 Rector Christmas Bird Count Results

A Perfect Mineral for the Christmas Season

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: December 1, 2023