by Jia Tucker

A week before accepting a summer internship with Carnegie Museum of Natural History, I found myself standing on Forbes Avenue in front of Diplodocus carnegii, the statue that is an emblem of the vast institution.

I had never even stepped foot inside of the museum before June 2022. The career path I had formed in my head over the past few years had been wiped clean by a change of heart. To be honest, I only applied to this museum studies internship because of a moderate interest in the field — and it was paying.

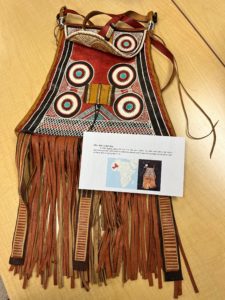

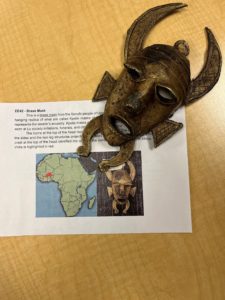

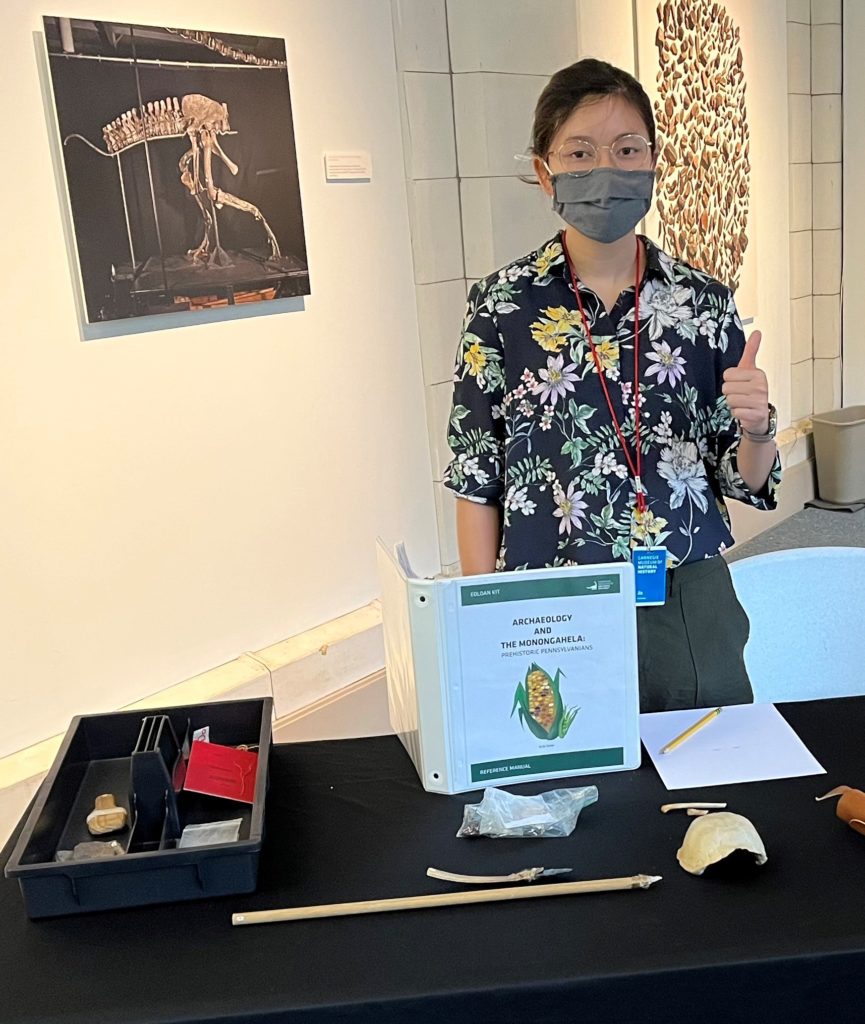

I was placed in the Education and Exhibitions departments. While beginning work in the Education Department, Program Officer Pat McShea tasked me with streamlining and modernizing one of the museum’s “Ed Loan” kits. These kits are borrowed by educators and used to create lesson plans that encompass a variety of subjects from paleontology to anthropology to zoology and beyond. He’d given me a popular, but complicated-to-use kit that focused on what we call the Monongahela, a precontact People whose settlements were concentrated in Western Pennsylvania, eastern Ohio, and northern West Virginia. The kit had a lengthy, approximately seventy-page manual and over thirty objects meant to be used for a lesson plan spanning two to three weeks. I had to pare it down to a dozen objects and two to three days of lessons.

Coming from an undergraduate perspective with limited experience in workspaces like the Carnegie, I was new to this kind of responsibility. It wasn’t just an essay that would only go through the eyes of a professor, but a tool for the public. The whole time I worked on the kit and my other project in the Exhibitions department, I questioned my ability to complete my tasks adequately. Although I have an intermediate background in anthropology and am no stranger to doing research, curating an educational resource with such free rein seemed beyond my expertise. It was overwhelming, but in a good way. That’s not to say that my Internship Supervisor, Renee, or Pat left me hanging high and dry. Early in the internship, Renee set me up with a list of the people I should reach out to in the museum, and that was, well, everyone. She had firmly yet kindly suggested that I not let this chance slip away.

So, I didn’t.

With some help, I started contacting program managers from various departments and setting up tours with curators of different collections. I got the chance to hear from people who are passionate about their field of study and eager to learn about what I had to say. It was a reciprocal learning environment that I hadn’t experienced until now. It wasn’t about a LinkedIn connection or a line in a resume. The person who printed all the posters had a name as did the person who developed all the content. What was to me one singular entity fractured into a chorus of different voices all striving to keep the museum alive, and all I wanted to do was contribute a verse. It’s always the people that make the effort worth it. Each person I spoke with would playfully try to convince me to join their field and indulge in their same joys. Although perhaps they were not-so-subtly disguising sincerity. Regardless, for the first time, I felt that flicker of potential. The smorgasbord of an undergraduate degree that I had been haphazardly holding together, hoping that eventually it would be “useful,” could finally stand on its own. The technicalities of it aren’t the important part anyways. Everyone I met came to the museum by both conventional and unconventional means. I’m no exception to the chaos of finding a purpose.

It’s a shame that as my bones started to settle and my shoulders relaxed into an office chair that was only ever meant to be temporary, I now have to take my leave. Even so, this has been the kind of chance that reminds me that there’s always more to explore up ahead. If you’re seeking a push or some great nugget of enlightenment, here it is. Meet as many perspectives as you can, ask as many questions as you can think of, and be brave. Don’t let it slip away.

Jia Tucker’s summer internship at Carnegie Museum of Natural History was part of the PA Museums Qualifying Diversity Program.

Related Content

Pitt Outreach Efforts Enriched with Museum Materials

A Summer Internship at Powdermill

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Tucker, JiaPublication date: September 6, 2022