Allegheny County Park Rangers consider themselves to be ambassadors for a public asset whose value has increased during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic: nine regional parks encompassing more than 12,000 acres of largely green space, laced with some 100 miles of multi-use trails.

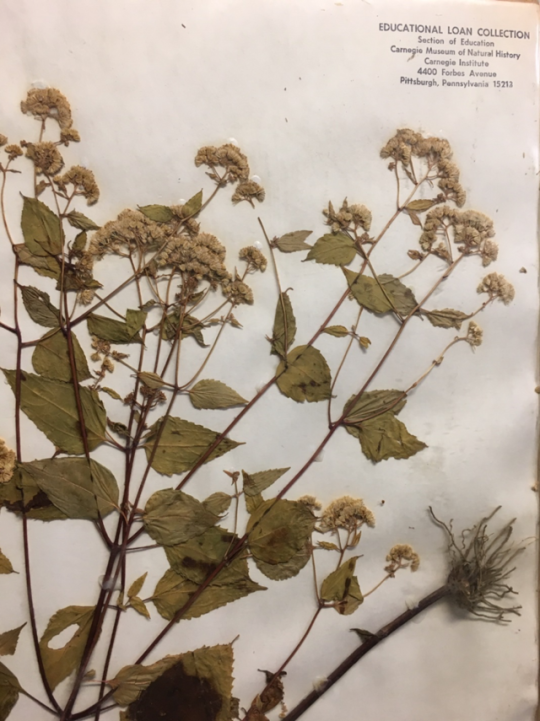

For Elise Cupps being an ambassador for this unique resource involves teaching a variety of audiences, including school groups, scout units, garden clubs, and library patrons. The Robert Morris University (BS) and University of Pittsburgh (MA) alumna is a five-year veteran of a program just six years old, and as the Park Ranger’s Coordinator for Education and Outreach she makes regular use of the CMNH Educator Loan Program.

In many County parks, Ranger programs about owls and bats utilize taxidermy mounts borrowed from the museum. “We could just hold our hands apart to show the difference in size between a screech owl and a great horned owl,” Elise explains, “but it’s far more effective to have the preserved birds on display for the participants to inspect themselves.”

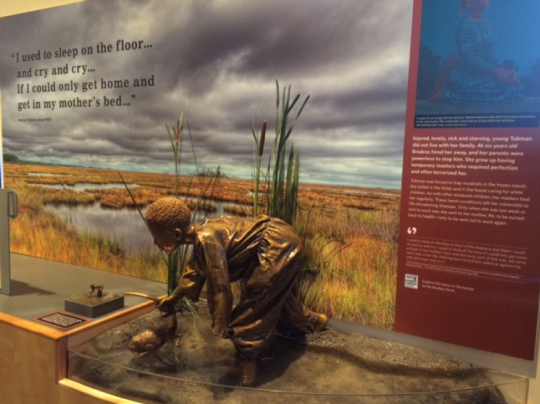

Other loans of museum materials enhance presentations that have ties to a specific park. Bison materials, including limb bones, hooves, and horn sheaths, for example, have been used for programs at South Park, where a small captive herd of the iconic prairie mammals have been a public attraction since the 1920s. Ranger programs about archaeology, which utilize authentic stone arrow points, adz heads, and fishing weights, make reference to a museum-led excavation in Boyce Park decades ago that documented how our region. was once the homeland of people known to science as the Monongahela.

During the past ten months, with the pandemic disrupting much of their planned program schedule, the Park Rangers paid close attention to their audience. “We’ve been fluid,” says Elise by way of summary. “We’ve made continual adjustments to meet the needs of groups – making live virtual presentations, sending pre-recorded videos, posting images and information on Facebook, sharing PowerPoint presentations – whatever it takes.”

Next week Elise will be borrowing a set of taxidermy mounts for upcoming programs about birds in winter. The means of program delivery has not been determined at this point, but it is a certainty that learning will occur.

Learn more about the Allegheny County Park Rangers.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.