Written descriptions for Carnegie Museum of Natural History summer camp, Wizard Academy, invite 8 – 10-year-old participants to experience a collision between “magic and science.” Based upon my recent experience with campers in the popular Harry Potter-themed program, the advertised subject could also include “history.”

During a discussion of poisonous plants with two dozen want-to-be wizards in the Hall of Botany, I drew the group’s attention to a display labeled “LOCAL SPECIES TO AVOID.”

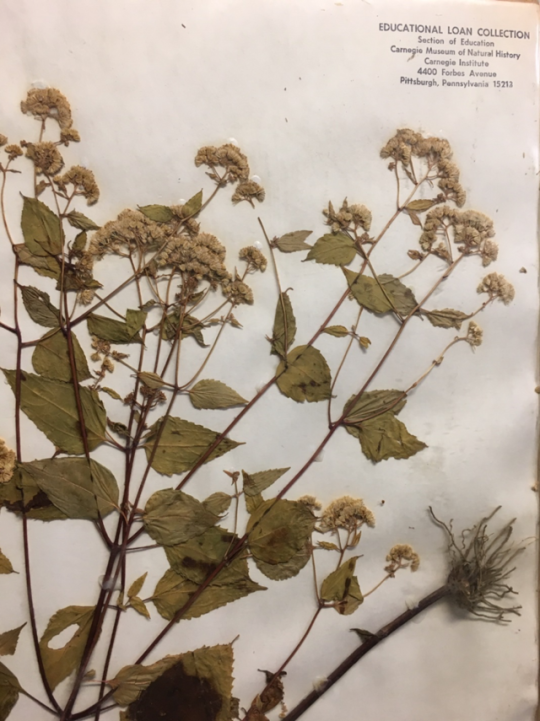

The focus for my remarks was white snakeroot (Ageratina altissima) a straight-stemmed and flower-topped species in the display’s front row. I explained how the plant’s common name is an historic reference to its alleged value in treating snake bites, and that its designation as a plant to avoid was based upon on its connection to an often-fatal illness know as milk sickness.

The disease, which occurred when people drank milk from cows that had fed upon white snakeroot, was a scourge of pioneer life during the early nineteenth century, the decades-long period when settlement across what was then the American frontier dramatically altered vast forests west of the Appalachians.

One of the campers assisted my narration by reading from a handout about how Abraham Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, died from milk sickness. When another camper asked how the plant-to-cow connection was “figured-out,” I confessed ignorance but promised to find out.

Much of the life-saving credit, I learned, belongs to a pair of women whose friendship crossed conflicting cultures of 1820’s Illinois; a frontier doctor, and an elderly fugitive of the federal government’s forced relocation of the Shawnee to territory further west. The doctor, Anna Pierce, lost family members to milk sickness and, based upon observations of disease occurrence, promoted the avoidance of milk drinking between June and the plant-killing frosts of autumn. The relocation resister, known to settlers as Aunt Shawnee, took Dr. Pierce into the woods to show her white snakeroot and explain the plant’s lethal properties. Pierce then conducted experiments to confirm the plant’s toxicity and shared her findings with other doctors.

More than 70 years later carefully controlled scientific studies documented year-to-year and geographic variations in the toxicity levels of white snakeroot, but it wasn’t until 1928 that the plant’s toxic chemical, an alcohol termed tremetol was isolated in a laboratory. Today, largely because of better pasture management, milk sickness is not a concern in commercial dairy operations.

The takeaway lesson, kindled when a ten-year-old camper’s question illuminated a nearly 200-year-old ethnobotany story, is to more fully value the indigenous knowledge of the vibrant Native cultures that continue to exist across our country.

(Information source: Natural History, July 1990, “Land of Milk and Honey” by David Duffy Cameron)

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.