by Patrick McShea

Participation in this year’s City Nature Challenge (CNC), April 28–May 1, 2023, is a great way to familiarize yourself with iNaturalist, an innovative cell phone app that powers the annual biological survey of metropolitan areas across the globe. Mastery of the easy-to-use technology during this self-paced bioblitz-style event can create positive outcomes long after the Pittsburgh CNC concludes and in places far beyond the event’s six county territory.

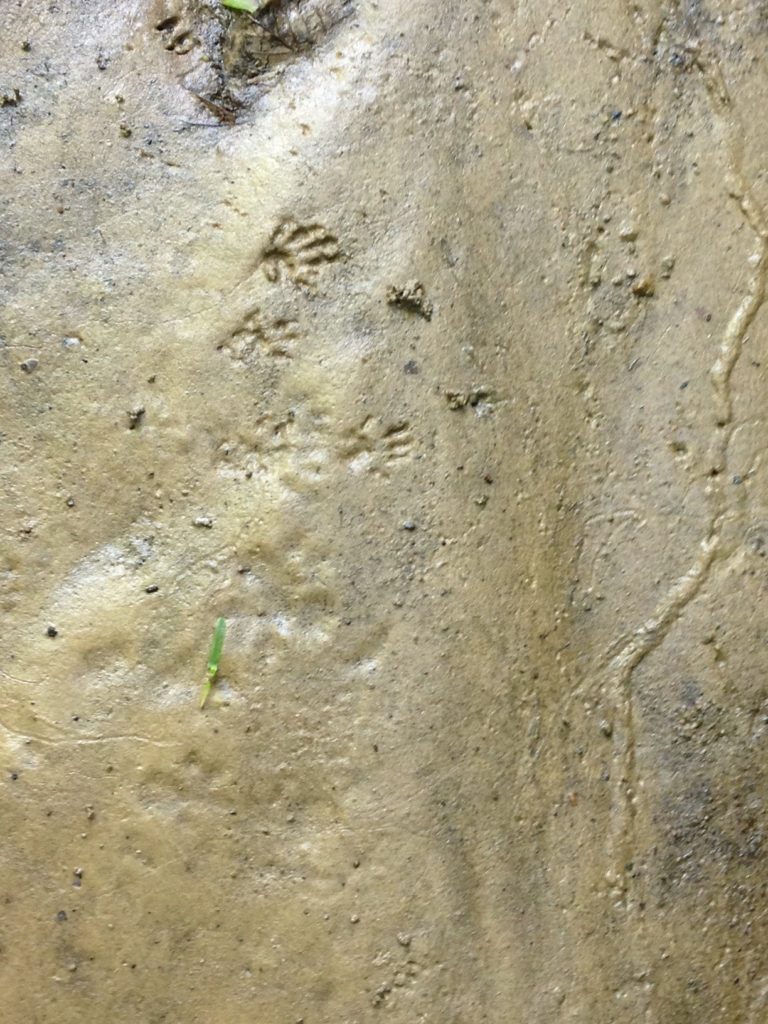

Although 2023 will be the sixth consecutive year for Carnegie Museum of Natural History to serve as a CNC city organizer agency, I didn’t become an active participant in the event until 2021. In 2021, I was among 446 participants who, in using our phone cameras to take and submit pictures, documented 7,045 observations of free-living plants, animals, and fungi in Allegheny, Armstrong, Beaver, Butler, Washington, and Westmoreland Counties. Our collective efforts verified and geo-referenced the presence of 1,219 different species at various locations in the surveyed territory.

My contributions, which came from four half-hour periods over as many days, amounted to only 29 observations, and for each of them I was able to include an accurate name of the observed subject in the submission form’s “What did you see?” line. iNaturalist, which is a joint initiative of the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society, functions amazingly well in identifying submitted images even when this question is ignored. The app provides users with impressive evidence of its image recognition capabilities by quickly supplying identification suggestions. This digital wizardry is only a starting point, however, because iNaturalist defines itself as “an online social network of people sharing biodiversity information to help each other learn about nature.”

Whether an observation is tentatively identified by the observer or through the powerful software, higher levels of identification certainty occur hours, weeks, or even months later when other users, who are focused on identifying observations, verify, refine, or even challenge identifications. Consistent verification by such reviewers can raise observations to “research grade,” indicating possible use in future scientific investigations.

Because I didn’t pay close attention to the network aspects of iNaturalist during the CNC, appreciation for my phone’s transformation into far more than a multi-category field guide came months later and more than 500 miles to the northeast during an early fall vacation in the Adirondack Park.

On a sunny mid-September afternoon, while my wife and I watched for birds and pitcher plants along a bog-crossing boardwalk that is part of the unique 14,000-acre campus of Paul Smith’s College, we were frequently surrounded by white moths with delicate black markings. When one landed close by I took its picture, then immediately submitted it as an iNaturalist observation. “Genus Cingilia,” I saw on the phone screen within 30 seconds.

Days later, when an email notification informed me that an observation reviewer had refined the identification to “Cingilia catenaria,” or the “Chain-dotted Geometer,” curiosity about the bog moths prompted a visit to BugGuide.net, a reliable site for information about insects and spiders in North America. Here a statement in the “Remarks” section of the species account raised an ecological question: “Locally abundant to the point of being a pest in some years, yet becoming increasingly rare over much of its former range in the Northeast.”

As I wondered whether the numerous bog moths had been a pest-level outbreak, I remembered someone who might be able to answer that question. The observation reviewer had identified herself on iNaturalist. Dr. Janet Mihuc is a professor at Paul Smith’s College who has been conducting a moth biodiversity survey on the college’s lands for the past six years. In an email exchange she was happy to discuss the bog moths and their role in the ecosystem.

I certainly consider C. catenaria common in our area. I am not aware of it being a pest but that may just be because our local bogs have no economic significance to humans so I doubt there is data on the amount of defoliation that the caterpillars can cause. Hopefully the caterpillars are an important food for migrant songbirds before they depart or for resident songbirds. Based on my data, adult moth species diversity peaks in July then drops steadily in August and September. I would expect caterpillar availability to show a similar trend.

Her generous sharing of information was completely inline with my experience as a CMNH educator asking museum scientists for clarification of concepts presented in current exhibits. The fact that the information exchange was brokered by a cell phone app did not diminish the learning that occurred.

Patrick McShea is an Educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Evidence Counts For Absent Creatures: City Nature Challenge

Naturally Pittsburgh: Big Rivers and Steep Wooded Slopes

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: April 18, 2022