By Gil Oliveira

In my previous blog, I wrote about the last Jurassic World movie, which ends with the rise of a new fictional Jurassic Age, where humans and dinosaurs must learn to coexist. The Jurassic is one of the most famous geological time-periods. But when exactly was the Jurassic? The Jurassic Period ran from 200 to 145 million years ago. A long time ago… To put it into perspective, the origin of our species, Homo sapiens, dates back approximately 300 thousand years ago, which also seems a long time ago, but represents only 0.007% of the entire history of the planet (4.5 billion years)! What happened on Earth the 99.993% of the time when we did not yet even exist?

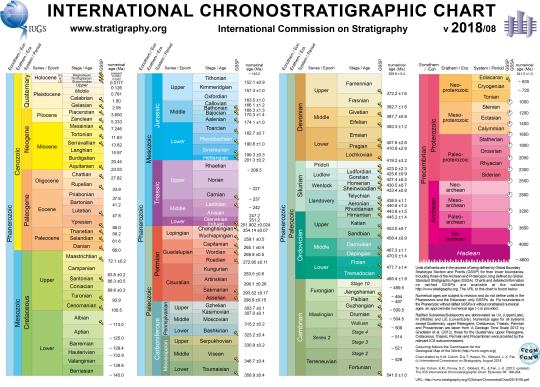

To understand earth history, natural history museums travel back through time. To do this they use a communication tool called the Geological Time Scale. In the same way we measure time with segments (such as years, months, weeks, and days), geologists subdivide deep time into useable, agreed upon units (eons, eras, periods, epochs, and ages).

But the Geological Time Scale is not exactly a calendar, because these time intervals are not equal in length like the hours in a day. Instead, divisions are based on significant events in the history of the Earth, that are detectable in rock, fossil and ice records, such as the extinction of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, which defines the beginning of the Cenozoic era.

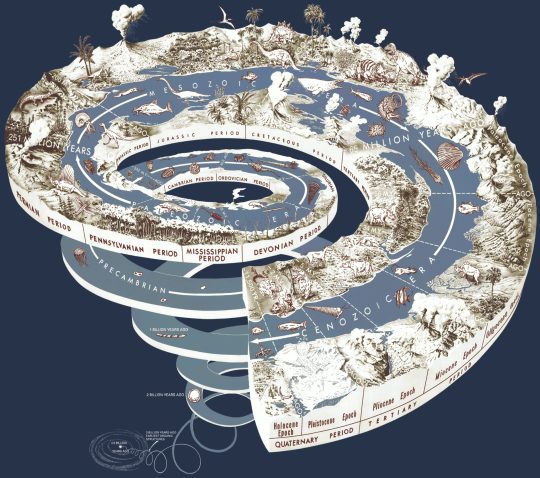

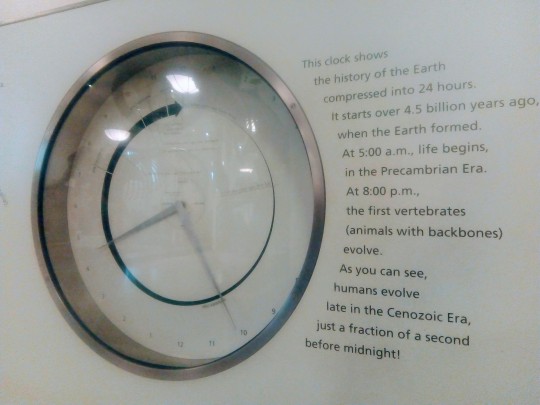

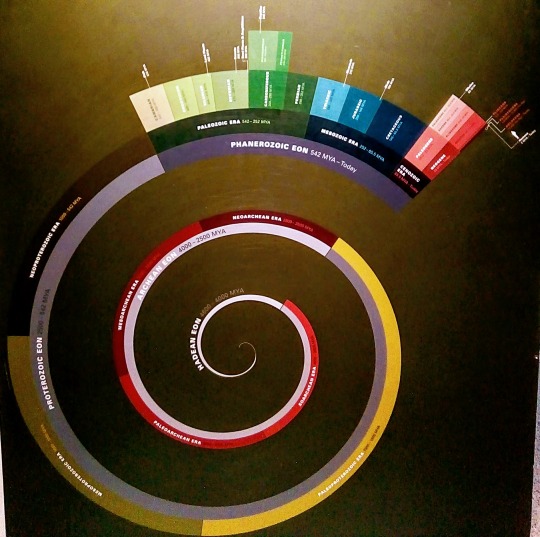

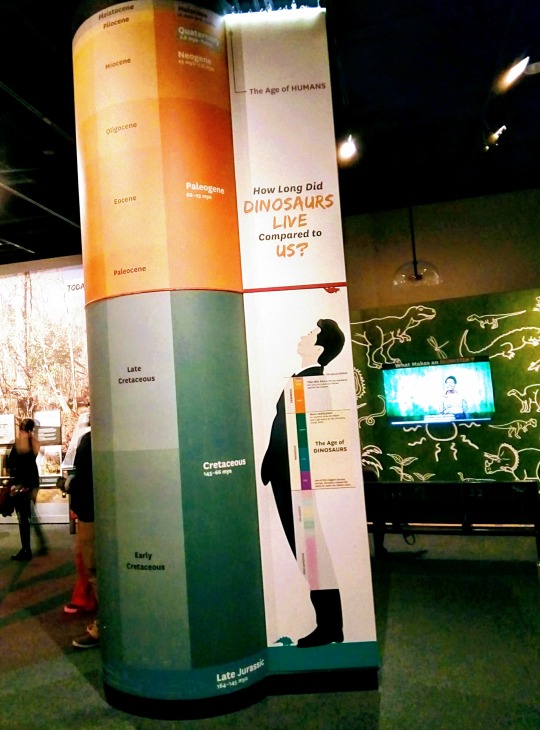

Museums don’t seek to teach the official chart of geologic time. But they seek to teach about deep time and the planet’s history, helping to put current times into a longer historical context. Museums use different techniques to make the geological time scale comprehensible. One approach is linear and usually consists of a strip of paint that represents the geological time scale rolled out on a surface. It was used for instance in the Objective Earth: Living in the Anthropocene exhibition at the Valais Nature Museum (Switzerland), which rolled out a linear poster around 30 feet long on the ground (and the wall). A second approach I have seen is more focused on aesthetics and takes the form of a spiral of time. Another technique is to take the age of the Earth and compress it into one year or one day. The American Museum of Natural History in New York used this approach with a 24-hour clock. The label indicates that life began at 5 am and the first vertebrates evolved at 8 am. As for the humans, they appeared just a fraction of a second before midnight.

Each approach has benefits and disadvantages. The Geologic Time Spiral for instance can be visually striking, but the perspective of the spiral’s depth runs the risk to lose any perception of the proportion of geological time, which is the main information. It may also give a false impression of accelerating events (geological, biological, climatic, human) as we move closer to the present.

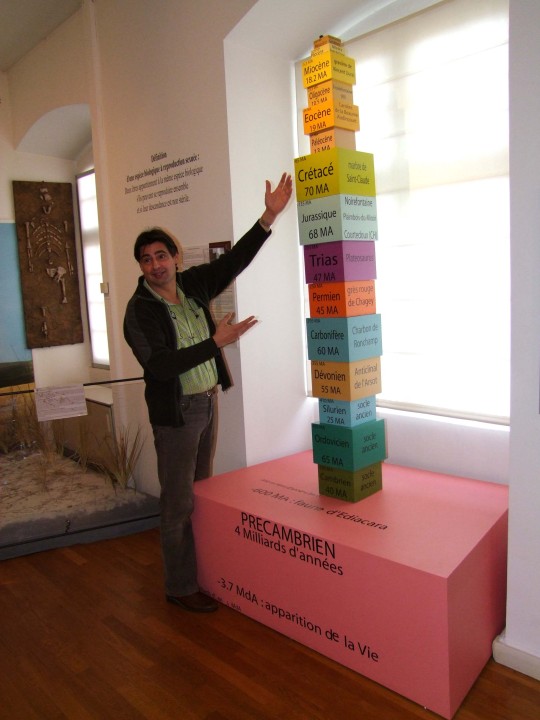

In 2007, the Cuvier Museum in Montbeliard (France) came up with a new way to represent the geological time scale. Thierry Malvesy, now curator of Geology Collections at the museum of natural history of Neuchatel (Switzerland), did it using cubes of different volumes. The advantage is to respect the proportions of time while allowing the public to see everything at a glance. It was used to explain the principle of biological evolution, emphasizing the importance of time in the evolution of life.

What is the best way to make the geological time scale understandable? There’s no easy answer. Each approach is a compromise in a way. The dinosaurs exhibit at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History uses both the spiral and the linear approach. This choice may only be temporary, as the new hall called The David H. Koch Hall of Fossils—Deep Time will open in less than a year. I wonder which approach they will use to help visitors connect to Earth’s distant past?

As the Carnegie Museum of Natural History is embracing the Anthropocene as a major theme for the future, it is important to place this newly proposed epoch in deep time. It is equally important for museums to find the best way to do it.

Gil Oliveira is postgraduate student working as an intern in the Section of the Anthropocene at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.