by Patrick McShea

Planning for field work resembles vacation travel preparation in a fundamental way. Much consideration is given to gathering all necessary gear, and the mere assembly of these items triggers a kind of mental departure that precedes the physical one.

As a former English major, I’ve learned to manage this sometimes disorienting state by reading or re-reading destination-related articles, essays, and books.

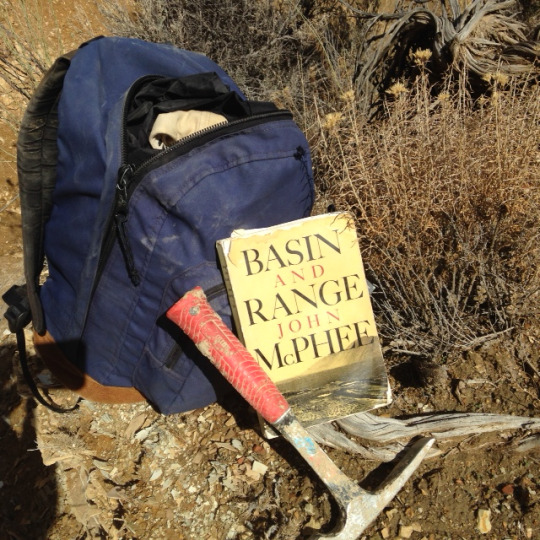

For the Elko, Nevada sites where Amy Henrici and I hope to collect frog fossils this fall, John McPhee’s “Basin and Range” (Farrah Straus Giroux, New York, 1980) has particular relevance.

The book recounts the author’s travels along Nevada’s Interstate 80 corridor in the company of renowned Princeton University geologist. McPhee successfully translates into layperson language the region’s “geology in its four-dimension recapitulations of space and time.”

Fossils, as signs of ancient life, add critical evidence to such recapitulations. Near Elko, far up in the high desert hills south of Interstate 80, we’ll search for frog fossils to further our understanding of Earth’s past.

Patrick McShea is a museum educator who is traveling through Nevada with Vertebrate Paleontology Collections Manager Amy Henrici to search for frog fossils. He frequently blogs about his experiences.