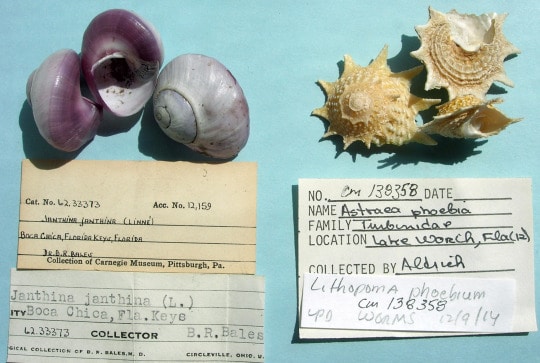

“What a pretty seashell, where did it come from?”

Perhaps the most important information that natural history museums keep about their specimens is where they came from. For many researchers, locality information is more important than the specimen itself. The specimen is useful to verify correct identification, but you can’t look at a specimen to determine where it came from.

As more and more museums share their specimen databases on-line, locality information is being used to document changes in distributions of organisms, including new occurrences of invading species, range shifts due to climate warming, and the disappearance of species becoming locally extinct.

To facilitate uses of locality information, museums are scrambling to georeference their specimens. This term refers to the electronic pairing of the historic recorded location for each collected specimen with an established system of latitude and longitude coordinates. Georeferencing can be tedious and time-consuming, what with interpreting messy handwriting, dealing with misspellings, and tracking down obscure names, some of which have changed over time. Once I spent over an hour and got only two specimens georeferenced.

The US National Science Foundation (NSF) recognizes the importance of georeferenced specimens to facilitate understanding of where species occur and how their distributions change over time. Consequently, NSF has awarded $58,762 to Carnegie Museum of Natural History as one of 14 collaborating museums on a $2.3 million grant for a project titled: Mobilizing Millions of Marine Mollusks of the Eastern Seaboard. The project is spearheaded by Rudiger Bieler at The Field Museum in Chicago.

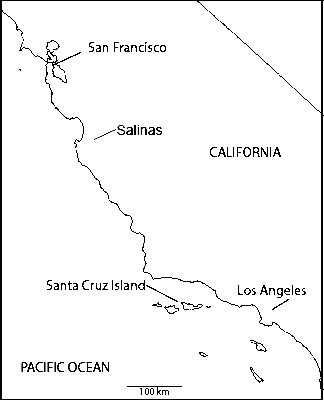

The main goal of the project is to georeference, and make available online, 535,000 lots representing 4.5 million specimens of marine mollusks (snails, clams, etc.) from the eastern USA. Only 15% of Eastern Seaboard mollusks in museums are currently reliably georeferenced. To facilitate georeferencing and promote standardization, each collaborating museum will focus on georeferencing all lots from particular geographical areas. Notably, for the first time, these museum records will distinguish between live- and dead-collected specimens, important information given that shells of dead mollusks sometimes persist for hundreds of thousands of years, and can be moved by currents and other animals such as hermit crabs. Whether or not a shell was collected alive is therefore crucial information for studies of biotic change using mollusks.

For CMNH, this award primarily means support for georeferencing our 11,436 lots of marine mollusks from eastern USA. In addition, we will catalog the eastern US part of our backlog, image relevant type specimens, create an exhibit, and, the aspect I am most excited about is creating an IPT, or integrated publishing toolkit, which will allow automatic updates from our in-house database to our web presence in the InvertEBase Symbiota portal.

The grant-funded new public display will interpret our biologically, commercially, and recreationally important marine mollusks from the Eastern Seaboard, and showcase mollusk diversity. The display will appeal to anyone who has beachcombed shells. Labels will describe how scientists use modern and historical specimens to study change in marine ecosystems over time. My hope is that visitors will learn that mollusks are diverse and beautiful, that museum collections are useful, and that evidence-based studies show ecosystem changes.

The Eastern Seaboard region includes 18 states, nearly 6,000 km of coastline, and about 3,000 molluscan species. Boundaries, from Maine to Texas, stretch from the shore outward to the edge of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone. The 14 collaborating U.S. collections contain 85% of all Eastern Seaboard marine mollusk museum holdings. These museum holdings average 8 specimens per lot – a lot is one species from one place at one time.

One hundred million mollusk specimens have been documented in natural history collections across North America. Each mollusk species in these collections average 1100 individuals, revealing geographic and morphological variation, and making mollusks among the best sampled group of metazoans, or multi-cellular animals. So far, freshwater and terrestrial mollusks have dominated digitization efforts of mollusks. This project is the first to focus on marine mollusks.

Shells are bio-archives. Shell skeletons record information about the animal and its environmental conditions throughout its life cycle. Shell material can be used to infer past ocean temperatures, seasonal fluctuations, and growth rates. Shell testing can reveal presence of trace elements and pesticides, allowing detection and identification of marine contamination and pollution.

In addition to their use in documenting what lived where and when, mollusks are important in other ways. Shells bring us joy when we find them on the beach. And many of us eat them. In 2016, three of the top 10 most valuable fisheries in the US, worth hundreds of millions of dollars, were mollusks: scallops, clams, and oysters.

Timothy A. Pearce, PhD, is the head of the mollusks section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is the biggest snail?