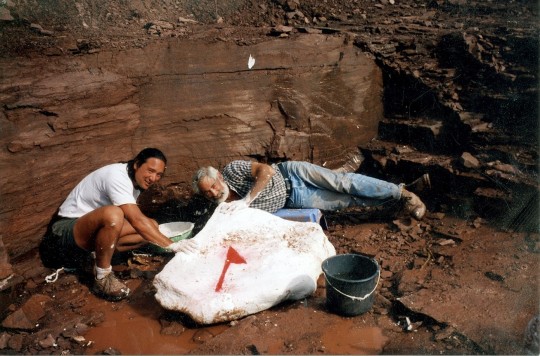

The formal publication of some of the Bromacker discoveries took more time to complete than others, and our most recently pubished fossil, Martensius bromackerensis, holds the record in that regard. Four nearly complete specimens of Martensius were collected from the Bromacker quarry between 1995–2006. The first, discovered by Thomas Martens and his father Max, came from a jumbled pocket of fossils. Unfortunately, muddy groundwater had penetrated cracks in the subsurface of this portion of the quarry and coated and eroded bone present along these cracks. Despite this damage and the lack of a skull, we could identify the specimen as a caseid synapsid (synapsids, also known as mammal-like reptiles, are a group of amniotes whose later-occurring members gave rise to mammals).

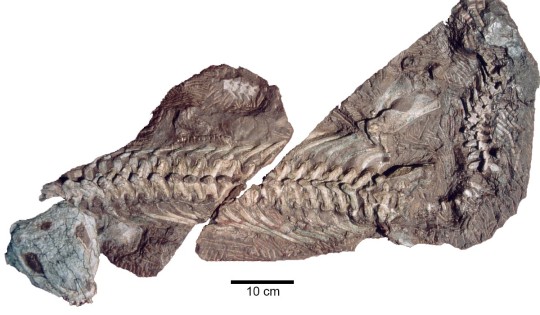

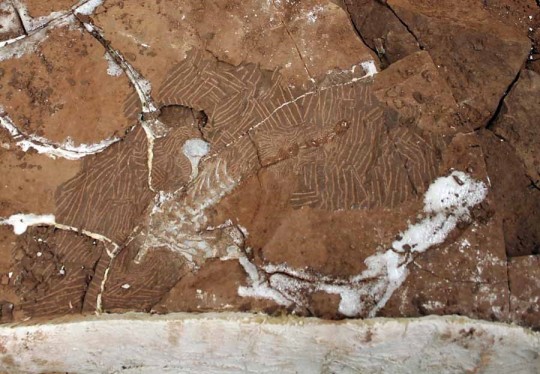

The next specimen was discovered in 1999 by Georg Sommers (Preparator, Museum der Natur, Gotha), who prepared the fossil. It consists of a vertebral column, ribs, some limb bones, and a few scattered skull elements. Unfortunately, a more complete skull was needed to allow for comparison to other caseids, some of which are based only on skull material. It wasn’t until the discovery of two more specimens in 2004 and 2006 by Stuart Sumida and Dave Berman, respectively, that the long sought-after skull was found. Preparation of these specimens took a long time due to their size and the considerable amount of rock covering the bones in some of the blocks. My promotion to Collection Manager in 2005 left me with considerably less time to prepare fossils. Other preparators were asked to help with the preparation at both Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH, Dan Pickering and Tyler Schlotterbeck) and in Dr. Robert Reisz’s lab at the University of Toronto at Mississauga (Diane Scott and Nicola Wong Ken). Robert was originally slated to lead the study, but other commitments prevented him from working on it, so Dave took over.

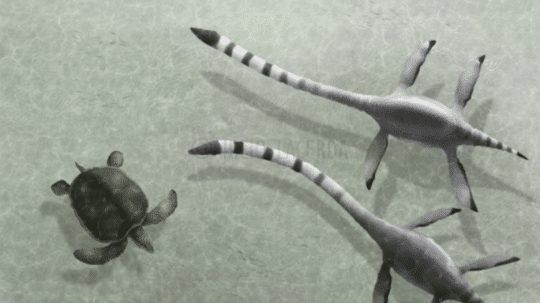

Besides preparation, the scientific study and publication of the specimens required illustrations and photographs, most of which were done by Diane, Nicola, and Kevin. Andrew McAfee (Scientific Illustrator, CMNH) made skeletal and flesh reconstructions of the animal, as well as an illustration of two Martensius in their ancient habitat (see The Bromacker Fossil Project Part III for a link to this illustration). All of this effort was worth it, however, because besides adding to the diversity of the Bromacker vertebrate fauna, Martensius has an unusual life history.

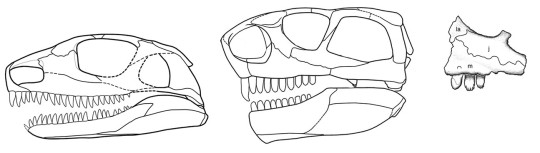

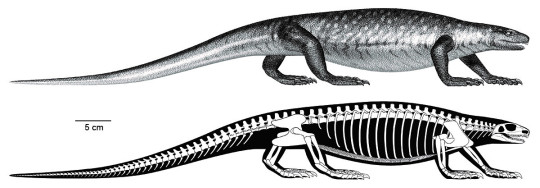

Caseid synapsids are a diverse, long-lived group known from the Late Pennsylvanian–Middle Permian epochs (~300–259 million years ago) of Europe, Russia, and the USA, and, with one exception, all are adapted to eating plants (herbivorous). The most advanced caseids (such as the enormous Cotylorhynchus romeri) have ridiculously small skulls when compared to those of carnivores, spatulate (spoon-shaped) teeth tipped with small tubercles (cuspules) for cropping vegetation, and huge, barrel-shaped ribcages to support a large gut for fermenting cellulose-rich plants. The exception is the earliest known (Late Pennsylvanian epoch, ~300 million years ago) caseid, Eocasea martini, represented by a single, incomplete juvenile specimen from Kansas. The teeth of Eocasea are small and conical, which indicate that it most likely ate insects. Because it’s skull and ribcage are of normal size, in contrast to juveniles of Martenius, Eocasea probably ate insects throughout its life.

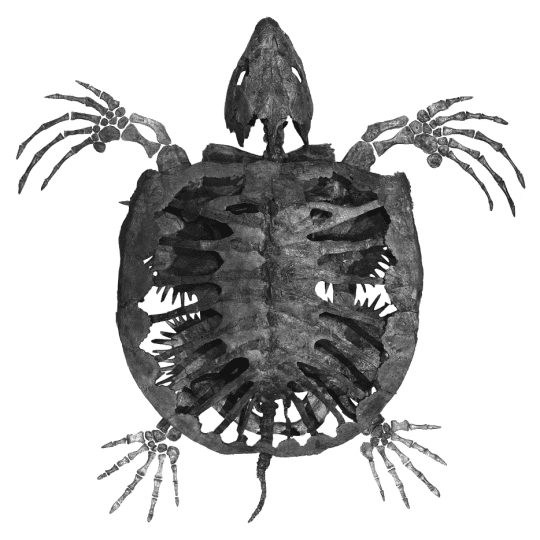

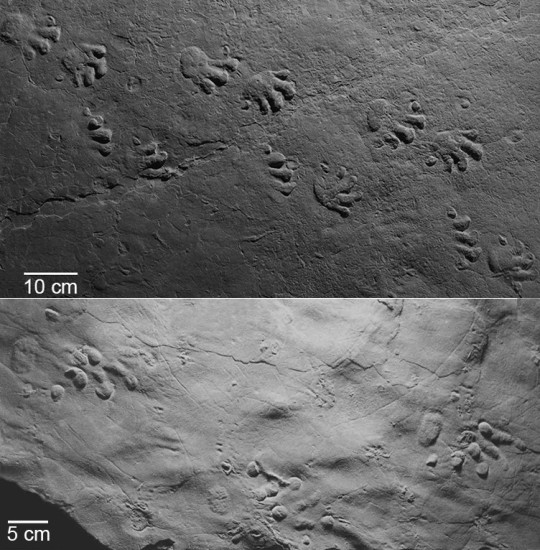

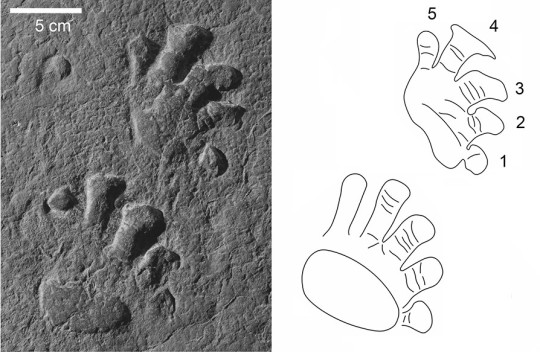

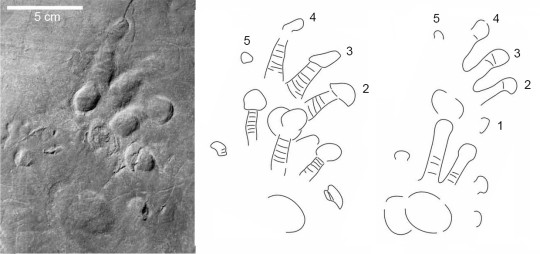

Martensius has a modestly expanded ribcage and a small skull, suggesting that it was herbivorous. Furthermore, the feet of Martensius, like those of other caseids in which the feet are known, are large, with massive, elongated, strongly recurved claws. Martensius also has a well-supported hip region that may have enabled it to rise on its hind legs to reach and tear down overhead branches to feed upon.

The upper and lower teeth of the adult Martensius differ from those of more advanced caseids in being triangular and lacking cuspules. The upper jaw teeth of the juvenile resemble those of the adult, but the lower jaw teeth are more numerous—31 in the juvenile compared to 25 in the adult—and surprisingly, they resemble those of Eocasea. Dave concluded that juveniles of Martensius had teeth adapted for eating insects, which were replaced by an adult dentition that would’ve been good for cropping plants and piercing insects. Remarkably, the juvenile Martensius apparently died while in the process of replacing its juvenile dentition with that of adults.

So why have different juvenile and adult dentitions? Modern animals that eat fibrous plant matter have micro-organisms called fermentative endosymbionts in their large guts, which break down difficult-to-digest plant matter via fermentation. It is assumed that early fossil plant-eaters with broad ribcages also had large guts housing fermentative endosymbionts. Prior to the discovery of Martensius, other scientists hypothesized that early herbivores acquired endosymbionts by eating herbivorous insects that already had these microbes in their guts. In Martensius, the introduction of endosymbionts apparently occurred during the juvenile, insectivorous stage of life, which set the stage for adults to add plants to their diet.

The generic name Martensius honors Thomas Martens for his discovery of vertebrate fossils at the Bromacker quarry and his perseverance in maintaining a highly successful, long-term field operation resulting in the discovery and publication of the exceptionally preserved Bromacker fossils. Bromackerensis refers to the Bromacker quarry, the only locality from which this species is known.

Stay tuned for my next post, which will feature some terrestrial dissorophoid amphibians.

For those of you who would like to learn more about Martensius, here’s a link to the 2020 Annals of Carnegie Museum publication in which it was described.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.