by Serina Brady and Mariana Marques

For centuries, naturalists have collected the living world with the primary goal of understanding the diversity and complexity of our planet. In vast shelves and cabinets located in natural history museums, we find a diversity of specimens used daily by researchers, students, naturalists, and conservationists from around the world. These collections are not just archives of the past, but they also play a crucial role in addressing present-day challenges. By documenting the diversity of life, natural history collections provide a wealth of information that can be used to tackle issues such as climate change, pandemics, pathogen dispersals, deforestation, habitat fragmentation, and biodiversity loss. They can be considered the world’s most comprehensive and complex library, serving as a valuable resource for understanding and addressing the health of our planet.

Each specimen can be seen as a unique document or book recording an aspect of life on Earth at a particular time and place. They testify to the existence of a given species in a given locality and at a particular time, and they have a fundamental role as a guarantee of the scientific method: they allow objective observation that can be replicable. Natural history collections are an unparalleled source of information. For instance, a single bird or reptile specimen can provide data on its species, its habitat, its diet, and even its health. This wealth of information continues to allow researchers to understand better the past, the present, and the future of biodiversity, as well as the health of our planet – from local communities to the entire Earth.

These collections are usually housed in natural history museums. These museums are research, conservation, education, and public outreach hubs. Their collections are not limited to public exhibitions; in fact, the majority are housed in storage locations, generally out of sight and knowledge of the public. The process of collecting and storing these specimens is methodical. Each specimen is carefully collected, identified, and cataloged, then stored in a controlled environment to ensure long-term preservation. This process ensures that these specimens, often fragile and irreplaceable, are protected and can continue to be used for research and education for future generations.

Natural History Collections: a Tool to Face Global Changes

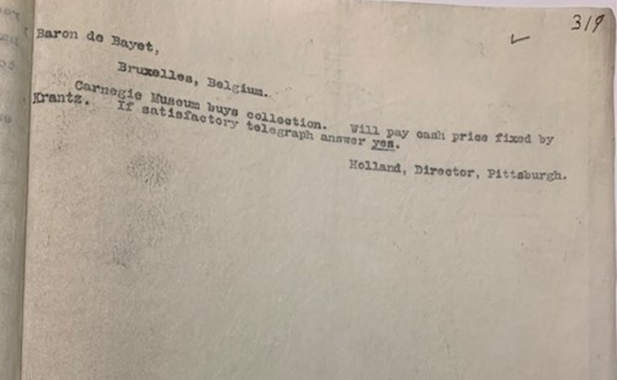

How can a specimen collected more than 100 years ago still be relevant today? Historical collections, like the one housed at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, provide baseline data points. These initial measurements or observations serve as a starting point for future comparisons. By providing a snapshot of life on Earth at a particular time and place, these specimens allow us to study change over time. The first and most crucial step is to gather those baseline data points!

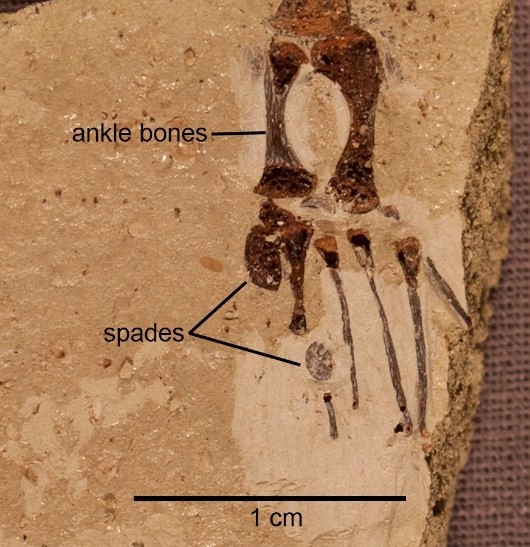

From their early days, natural history collections’ primary goal was to inventory all life on Earth. However, with new cutting-edge technology, researchers can recover different data from historical specimens, data that the original collector didn’t even imagine. For example, when birds were collected from the U.S. Rust Belt, collectors didn’t realize that the specimens would be used to infer information about the history of pollution. Similarly, in the early twentieth century, the collectors of salamanders in the Appalachian woods didn’t even realize that some of those specimens were already infected with a pathogen that is devastating some of the world amphibian populations today.

However, because specimens were collected, we can now map the expansion of this pathogen through time or trace the amount of black carbon in the air over time through birds’ feathers to help fight and understand climate change. Part of the job of Collection Managers like us is not just to preserve and maintain the existing collections, but also to anticipate and predict the questions future researchers will be asking. This proactive approach ensures we gather today’s data to answer tomorrow’s questions. Specimens collected over a century ago are actively used today to answer questions about current and future environmental changes.

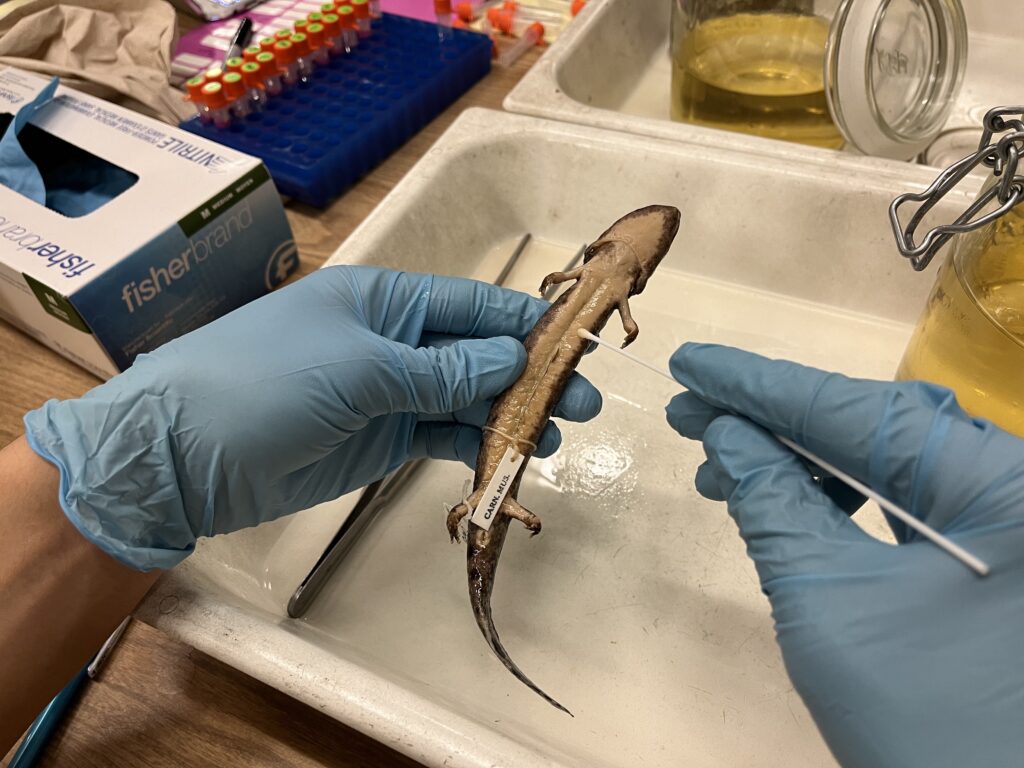

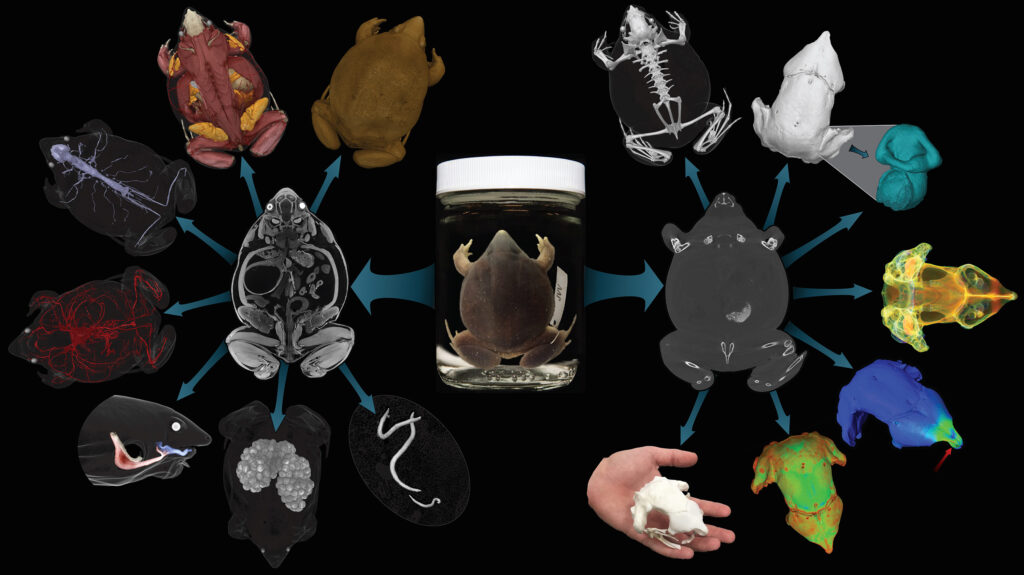

New applications of technologies, such as computed tomography (CT) scans, provide novel insights and usages for specimens. CT scans allow a complete 3D model of a specimen, including access to its internal morphology without damaging it. Using next-generation sequencing, scientists can use fragmented and degraded DNA for advanced analyses such as phylogenetic and phylogeographic analysis. These specialized methods allow us to study species’ evolutionary relationships and geographic distribution. These advanced techniques are just some of the ways natural history collections are being used to push the boundaries of scientific knowledge.

A Biodiversity Backup

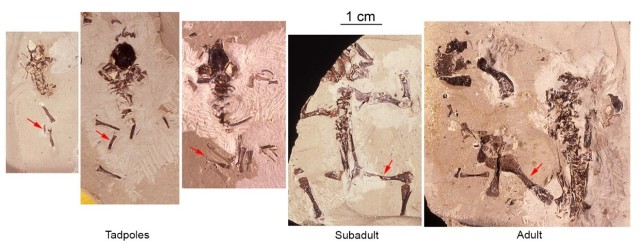

Continuing to grow our collections is not only scientifically essential but undeniably needed. Currently, 1.8 million species have been formally described to science, although worldwide experts predict that around 8.75 million species still await to be discovered, described, and named. Given current extinction rates, we are racing against time to describe the remaining 86% of the world’s species, many of which may become extinct before we know they even existed!

New species of birds, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and insects continue to be discovered worldwide, sometimes based on specimens tucked away in a museum for decades! These collections are not just archives of the past but also living libraries that continue to grow and evolve as new species are discovered. Each new discovery adds to our understanding of the natural world and underscores the importance of these collections in documenting and preserving Earth’s biodiversity. These new specimens contribute to our most significant and longest dataset of the natural world. But just as a library that stops acquiring new books, a natural history collection that doesn’t add new specimens will eventually lose its scientific value and relevancy. If we don’t continue to add physical proof of today’s biodiversity, we create unfillable gaps in one of our most powerful natural history data sets. Today is tomorrow’s past, and natural history collections act as a biodiversity backup of our planet!

Serina Brady is Collection Manager of Birds and Mariana Marques is Collection Manager of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Risk Assessment, or How to Keep Your Collection Intact

Type Specimens: What Are They and Why Are They Important?

Staff Favorites: Dolls in the Museum’s Care

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Brady, Serina; Marques, MarianaPublication date: August 16, 2024