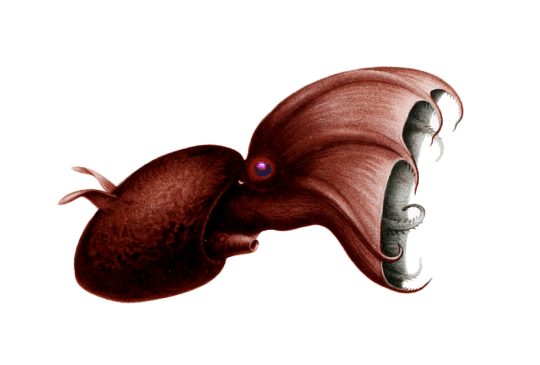

The Vampire Squid is your go-to mollusk for Halloween. It’s covered with glow-in-the-dark spots, and it can hoist its cape-like webbed arms over its head to transform into a pumpkin shape complete with outward-pointing fleshy spines. But wait, there’s more. With the largest eyes relative to body size of any animal, this has got to be the cutest Dracula you ever saw. And the scientific name, inspired by the cloak-like webbing and the dark body color, literally translates to “vampire squid from hell.”

The Vampire Squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis) is an extreme deep-water cephalopod more closely related to octopuses than to squids. It is so bizarre that scientists classify it in its own taxonomic order, Vampyromorphida, to show that it differs markedly from other living cephalopods. Like octopuses, it has 8 arms with webbing between them, but unlike octopuses that have suckers on the entire length of the arms, the Vampire Squid bears suckers only on their outermost half. The prominent feature on the arms of the Vampire Squid are fleshy spines or cirri. In addition to the eight arms, it has two velar filaments, in pouches in the webbing, that are analogous (and maybe homologous) to the two long tentacles of squids.

Regarding superlatives, the Vampire Squid has the largest eyes relative to its body size of any other animal, a detail noted in the Guinness World Records. A fully-grown individual can be 28 cm (11 inches) long with eyes 2.5 cm (1 inch) in diameter. Adding to the cuteness factor, they have adorable ear-like fins, which adults use for swimming; juveniles also have fins, but primarily use jet propulsion to move around.

They live in the lightless ocean depths 600-900 m (2000-3000 feet) deep in temperate and tropical oceans world-wide. The ocean at these depths is an oxygen minimum zone with so little dissolved oxygen that most complex organisms cannot survive. But the vampire squid survives perfectly well with a low metabolism and blue blood that is more efficient at carrying oxygen than that of other cephalopods. They use ammonium in their tissues to regulate their buoyancy (ammonium is a wee bit lighter than water), reducing the need for active swimming. Living in the oxygen minimum zone probably helps it to avoid predators.

If disturbed, the Vampire Squid kind of turns itself inside-out into the “pumpkin” or “pineapple” posture by curling its arms and webbing up to cover the body with the spiny cirri pointing outward. Their body is covered by photophores, or light-emitting organs, which they can use to flash a wide range of patterns. In the pumpkin pose, they conceal most of the photophores, but they can light up the tips of the arms and wave them around to distract predators. If it gets really annoyed, the Vampire Squid can release a sticky cloud of luminous mucus that glows for nearly 10 minutes, presumably long enough for the Vampire Squid to make a get-away into the inky darkness.

Much of what we know about their behavior comes from videos made by Remotely Operated Vehicles. It is hard to keep Vampire Squids alive in aquariums at the much lower pressure of our human world, but the Monterey Bay Aquarium succeeded for a while and has some great videos. Aquarium scientists were able to solve the mystery about what the Vampire Squid eats. No, it doesn’t eat blood! It eats detritus (organic debris), also known as marine snow. As the Vampire Squid drifts in the current, any debris that touches an extended filament is moved by the creature’s arms to its mouth. Unusual for being the only known cephalopod to eat non-living food, the Vampire Squid is adapted to eat material that falls through the oxygen minimum zone. Marine snow includes dead bodies, feces, and a lot of mucus from above, and because of the mucus, it is sometimes jokingly referred to as marine snot.

I imagine if Dracula learned about the Vampire Squid, he might exclaim, “I thought it was eating blood, but it’s snot!”

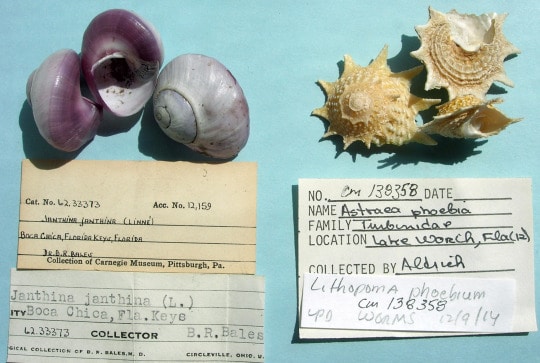

Timothy A. Pearce, PhD, is the head of the mollusks section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Extremely Rapid Evolution of Cone Snail Toxins