by Jay Margolis

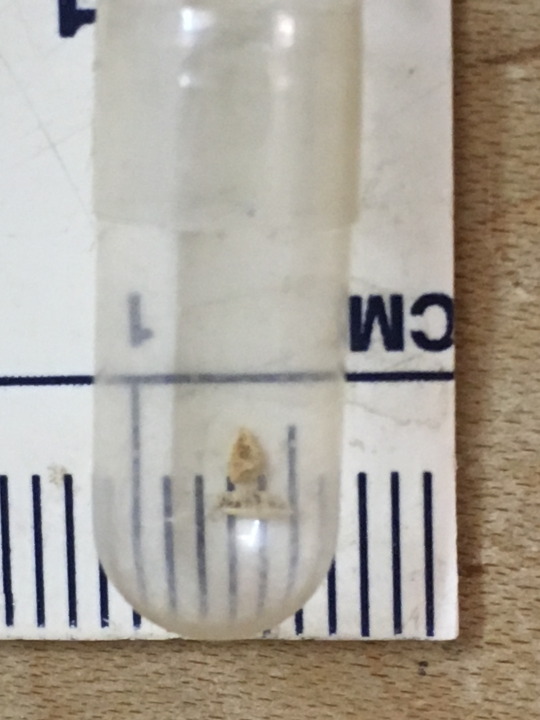

It can be difficult to find fossils when working on a microscopic scale. The partial jawbone and bone fragment above are each less than a centimeter (0.4 inches) in maximum diameter, but their small size makes them no less important to paleontologists and other researchers. Even diminutive fossils such as these can be used to help scientists determine the diet or behavior of extinct animals, as well as to piece together what kind of environment they lived in.

Even with the help of microscopes, it can be hard to tell such fossils apart from the tiny rocks and sediment that they are often mixed in with. After spending a long amount of time practicing and studying, telling fossil apart from rock can become easier. However, for those who have not had as much practice, there are a few easy ways to help distinguish the two.

One of these ways is to look for striations, or organized and consistent lines. These lines are all oriented in the same direction and can be seen on the surface of some fossils as an indicator of past bone growth. Another way is to look for pores, circular holes that would be visible in a cross-section of a fossil bone. These holes indicate where blood vessels once carried nutrients throughout the bone.

Both of these textures can potentially be seen in a disorganized fashion on rocks and minerals. However, seeing these two textures together, and arranged in an orderly way, is among the best indicators that the rock you thought you were looking at is actually a fossil.

Jay Margolis is an intern from Chatham University working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.