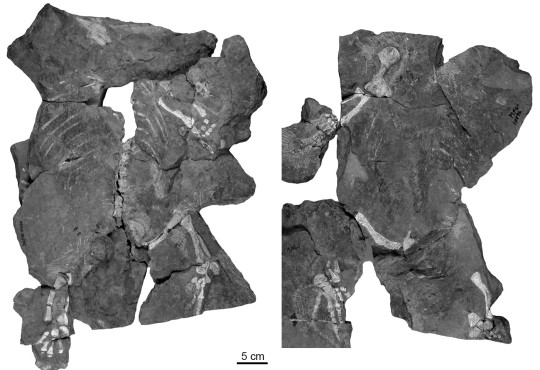

Holotype specimen of Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus, preserved in couterparts. Photographs by Dave Berman, 2010.

Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus was discovered by Thomas Martens and his father Max in 1995 in the same pocket of fossils from which the first-discovered specimen of the herbivorous basal synapsid Martensius bromackerensis was recovered. Because numerous fossil animals were jumbled together, Thomas and Max weren’t able to collect individual specimens from the bone pocket using our standard technique of surrounding a specimen in a plaster and burlap jacket. Instead, they collected all the individual pieces of rock that contained bone or at least appeared to contain bone, as most rock pieces were coated in goopy mud. Thomas cleaned the rock pieces with water to reveal the bone, and then pieced together the various specimens.

He eventually sent us the specimen that became the holotype of Tambacarnifex, along with pieces that he thought might go with it. Dave and I spent hours piecing together the remainder of the skeleton, and we searched the collections at the Museum der Natur, Gotha for missing pieces in subsequent field seasons. The majority of the specimen was recovered, but the skull, a few vertebrae, and distal finger and toe bones are missing. A rock piece with the greater portion of a lower jaw with teeth was also collected from the bone pocket, though it couldn’t be associated with the skeleton and may represent a second individual. A lot of bone was lost from the specimen, but impressions of missing bone were preserved, which proved useful for identifying wrist and ankle bones, among others. Dave used a white pencil to color in the bone impressions so they would stand out for study and in photographs of the specimen. Ultimately, we realized that Martensius and Tambacarnifex were preserved one on top of the other, though separated by several inches of rock.

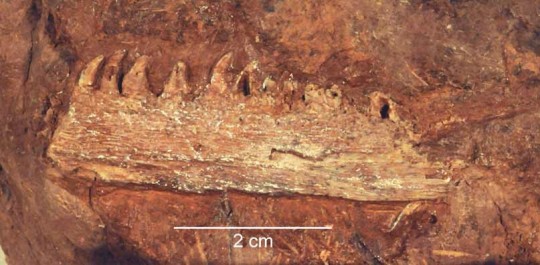

The lower jaw piece of Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus. Photograph by Dave Berman, 2008.

The teeth of Tambacarnifex preserved in the lower jaw are strongly recurved and flattened side-to-side, which, along with other features preserved in the skeleton, indicate it is a member of the basal synapsid group (family) Varanopidae and in the subfamily Varanopinae. The Varanopidae have been likened to the actively predaceous modern monitor lizards in the family Varanidae, hence the similar name. Varanopids were the most diverse and longest-surviving basal synapsids, being known from the Late Carboniferous–Middle Permian (~309–260 million years ago) of North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa. With their sharp, recurved teeth and a gracile skeleton, scientists think varanopids were agile predators, at least compared to other animals of their time. They range from about 12–78 inches in length, with the smallest ones probably being insectivorous and the larger ones carnivorous. Tambacarnifex has an estimated body size of about 35 inches, and as a medium-sized varanopid with gracile limbs it would have been an agile carnivore, preying on on any of the Bromacker vertebrates that it could catch.

An articulated but incompletely preserved series of 11 vertebrae of Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus. Notice that the neural spines are low and subrectangular, so it is unlikely that they supported a sail, as occurs in some other basal synapsids such as Dimetrodon teutonis. The front of the animal is to the left. Photo by Dave Berman, 2008.

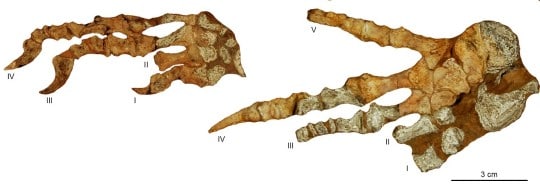

Unlike Dimetrodon teutonis, the other apex predator at the Bromacker, Tambacarnifex has broad, low neural spines that alternate in height. It differs from other varanopines in the shape and anterior inclination of its neural spines and in having greatly elongated and recurved bony claw supports in its hands and feet. The generic name Tambacarnifex was coined in reference to its position in the food chain: “Tamba,” for the Tambach Basin, which the holotype inhabited, and the Latin “carnifex,” meaning executioner, for its role as an apex predator. “Unguifalcatus” was derived from the Latin “unguis,” nail or claw, and “falcatus,” meaning sickle-shaped, in reference to the long, strongly recurved bony claw supports.

Incomplete front (left) and hind (right) feet of Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus. Notice the extremely long bony claw supports preserved on the first, third, and fourth fingers of the front foot and the fourth toe of the hind foot. I–V refer to finger and toe numbers. Photos by Dave Berman, 2008.

Illustration of Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus consuming a Dimetrodon teutonis carcass. Outline drawing by Matt Celeskey, colored (with permission) by Carnegie Museum of Natural History Vertebrate Paleontology Scientific Illustrator Andrew McAfee.

Stay tuned for the final post of this series, which will summarize what we’ve learned about the Bromacker. Click here if you would like to download your own copy of the outline drawing of Tambacarnifex consuming Dimetrodon to color in. The paper describing Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus can be viewed by clicking here.

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is it like to discover a new species?