March 9, 2024-March 9, 2025

Ancient Egyptian Objects Return to View, Museum Invites Visitors to Step Behind the Scenes and Follow the Conservation of More than 80 Ancient Objects

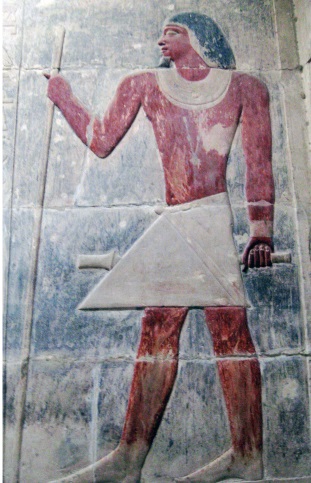

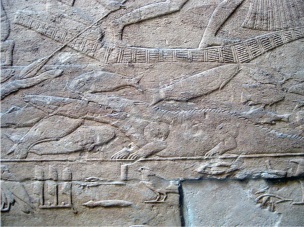

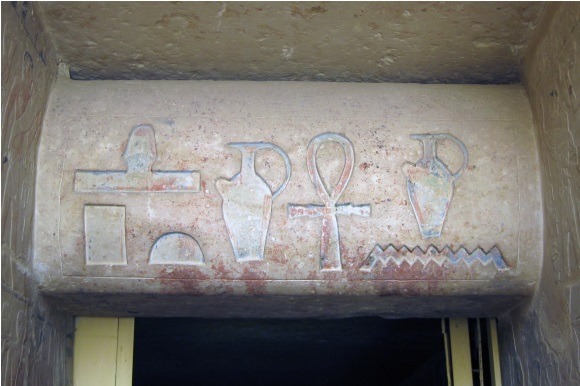

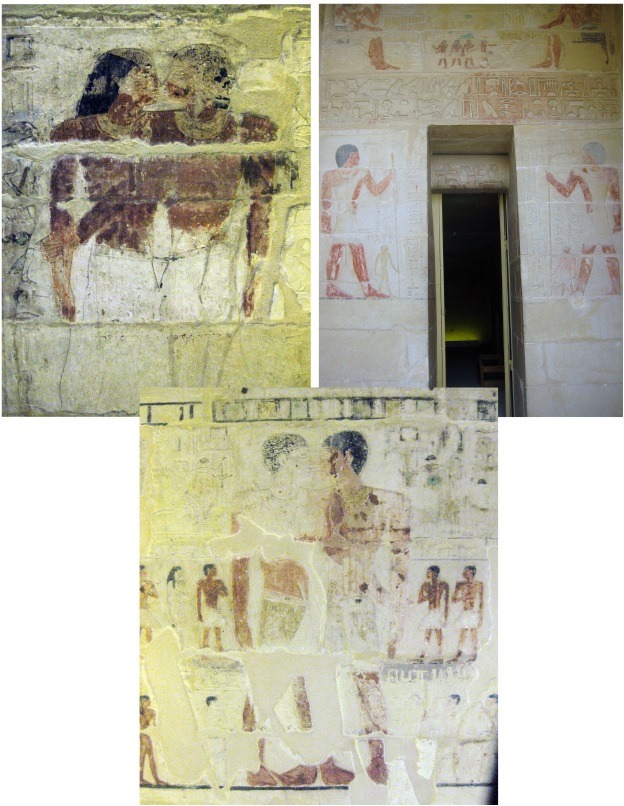

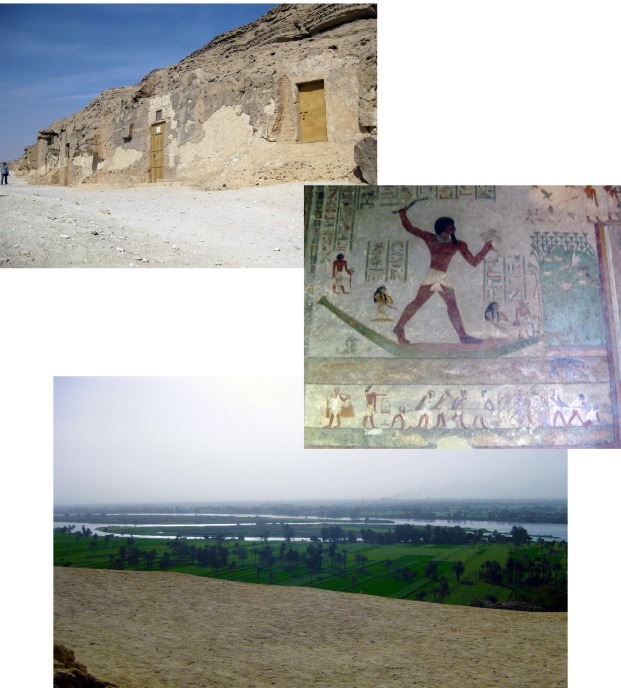

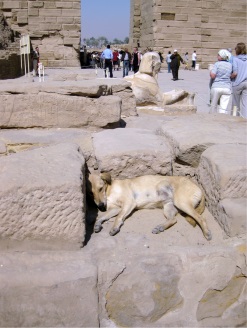

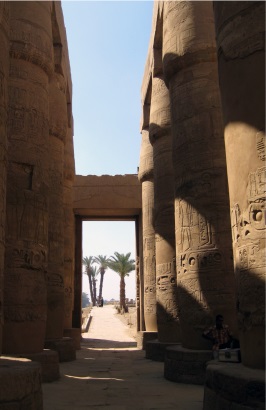

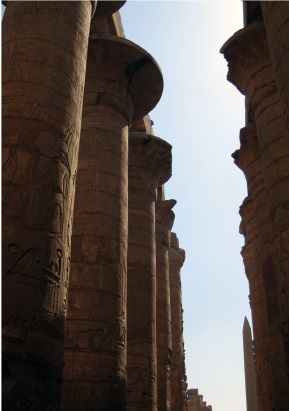

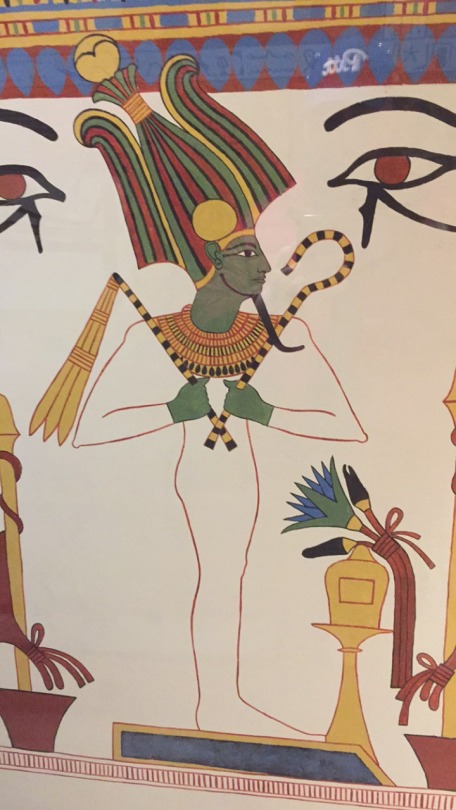

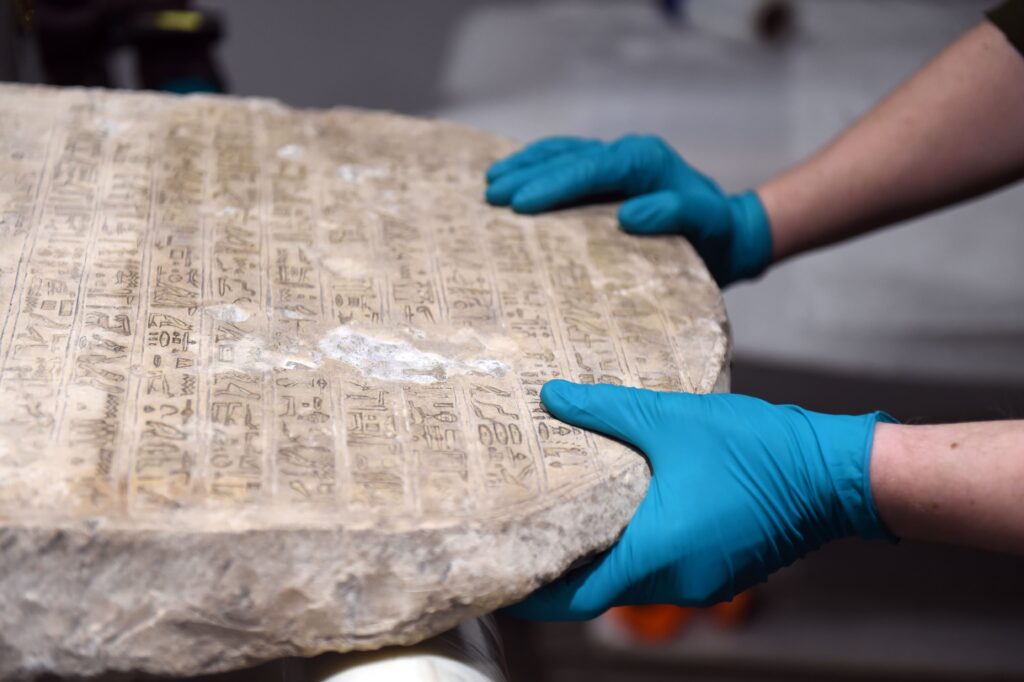

Carnegie Museum of Natural History presents The Stories We Keep: Conserving Objects from Ancient Egypt. The new exhibition, produced in house, opens the curtain on behind-the-scenes work and puts the art and science of artifact conservation centerstage. It also marks the return to public view of ancient Egyptian objects after the museum closed Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt in 2023 for necessary conservation. Opening March 9th and on view for one year, The Stories We Keep invites visitors to see these objects—cared for by the museum for more than a century—in a new light and to witness the work that will preserve them for future generations.

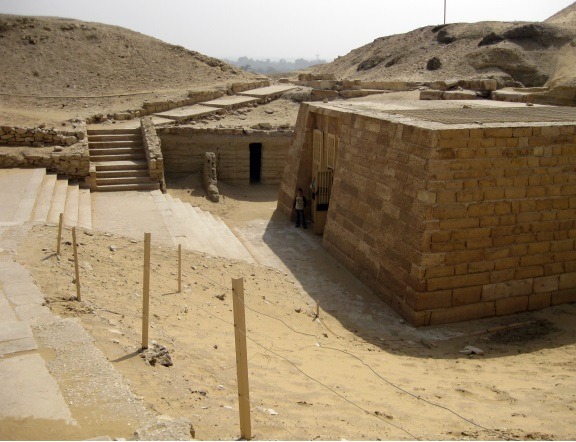

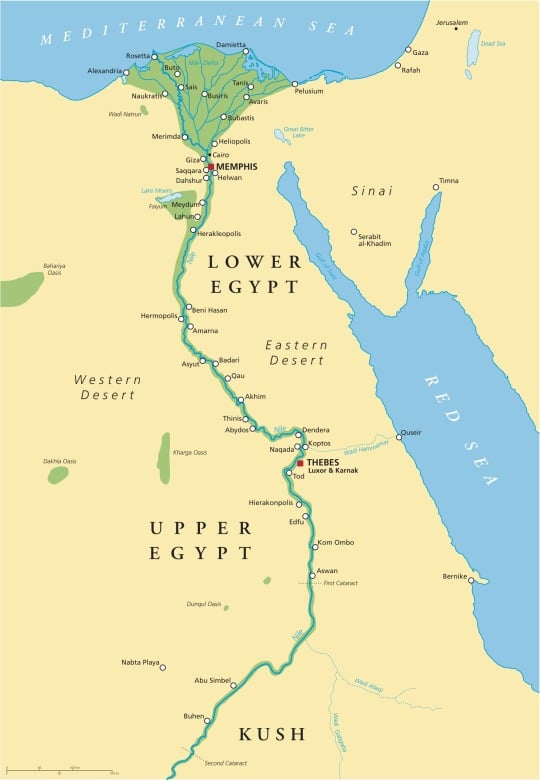

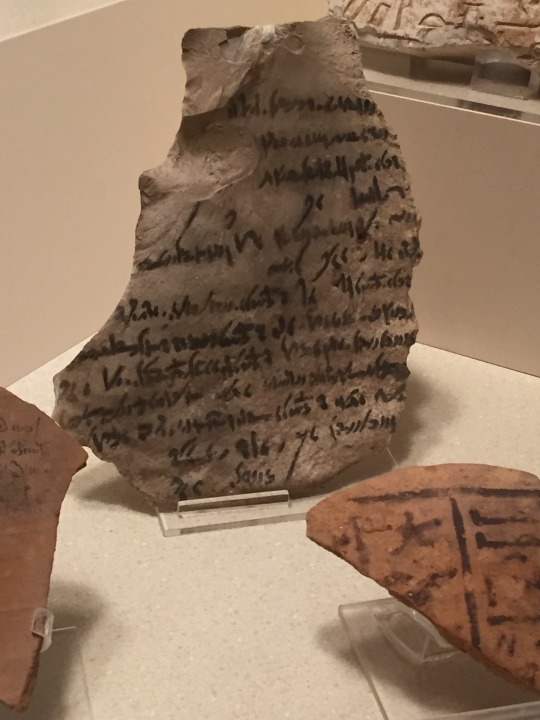

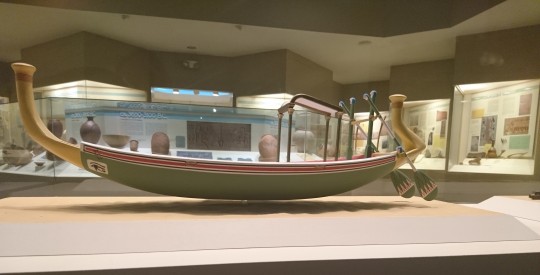

Every object in the museum’s care has stories to tell, about its creation and original use, its journey to Pittsburgh, and about the lives of those in ancient Egypt. The Stories We Keep features more than 80 items from ancient Egypt—including the 4,000-year-old Dahshur boat, one of only four in the world. CMNH invites visitors to engage with these objects like never before, have conversations with museum conservators, observe the care and restoration of objects in real time, and attempt the work themselves by reassembling replicas of ancient objects created with the assistance of 3D scanners.

Museum conservators will hold daily demonstrations and answer visitor questions about the objects and conservation tactics. Visitors can also submit questions by using a QR code, and the conservation team will address select entries in a video series accessible on the museum’s website and social media channels.

“We know how interested visitors are in ancient Egypt,” said Sarah Crawford, Director of Exhibitions and Design. “This exhibition allows visitors to satisfy their curiosity and watch as our Conservation team carries out their vital work caring for these ancient Egyptian items. We hope our fans gain new insights into these beloved objects and an appreciation for the hard work, dedication, and talent of our colleagues who safeguard them.”

The exhibition will prominently feature the Dahshur boat, one of four funerary boats still in existence from Egypt’s 12th Dynasty. In 2023, CMNH recruited Egyptian conservator Dr. Mostafa Sherif, an expert on ancient wood restoration, to treat the boat. He joins senior conservator Gretchen Anderson, who oversees the museum’s conservation operations, and project conservator Annick Vuissoz, who arrived at the museum last month to manage the ongoing conservation of 650 ancient Egyptian objects in CMNH’s care.

“This is an entirely new experience for visitors,” said Dr. Lisa Haney, Assistant Curator and Egyptologist. “It connects us to ancient people in a new way, encouraging us to think differently about our own everyday objects and the stories they tell. We hope to create new connections between the past and the present and highlight the science that helps preserve those connecting threads.”

The Stories We Keep is free with museum admission and runs until March 9, 2025. General museum admission costs $25 for adults, $20 for adults 65 and older, $15 for children aged 3-18 or students with valid student IDs, and $12 after 3 p.m. on weekdays. Admission is free for members and children aged 2 and younger. More information is available at CarnegieMNH.org.