by Bonnie McGill

Male Red-winged Blackbirds! For me, their calls and bright red shoulders are one of the signs that spring is really here. Mind you, this is no subtle sign of spring that takes an expert naturalist to notice. No, this is a sign of spring that slaps you across the face, as if spring is calling, “I’m here! CONK-A-REE! Look at me!” Next time you drive past a wetland area with cattails, there is a good chance you’ll see one or more showing off their red shoulders (the brown females are beautiful too). Red-winged Blackbirds have been back in western PA and announcing their territorial claims since March. Whether you live in the country or the city, bird watching is a great way to observe the change in seasons and connect with the nature around you (and in you).

As a member of the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership (CRSP) team I’ve been gathering evidence-based stories of how climate change is impacting natural processes in western PA. Since this week is the City Nature Challenge, folks might be paying closer attention to birds, creating an opportunity for museum scientists to explain what migratory songbirds in our region can teach us about climate change.

Since 1961 scientists at the museum’s Powdermill Avian Research Center (PARC) in Pennsylvania’s Laurel Highlands have been monitoring birds. In that time they have captured, studied, marked, and released almost 800,000 birds! This week, for example, PARC’s mist nets are temporarily capturing birds like the Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, House Wren, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, American Redstart, and Wood Thrush.

All of these species are migratory–spending the winter in the southern US, the Caribbean, Central America, and/or South America. Many fly across the Gulf of Mexico (!) on their way north in the spring. All of these birds share another trait–they are nesting earlier in the year than they once did. We will follow the Wood Thrush as an example of how many birds are responding to the warming climate.

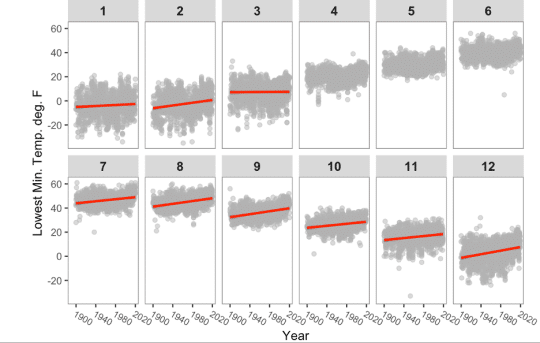

PARC’s unique 50 year dataset allows scientists to study how birds respond to long term changes, including the warming climate. Average April temperatures in the Laurel Highlands have already increased by two degrees Fahrenheit since the 1960s, and are projected to warm by another four to five degrees Fahrenheit by 2050. Warmer springs trigger earlier plant budburst. Insects, especially caterpillars, feast on buds and young leaves, which have less toxins than mature leaves. Caterpillars are the breakfast of champions (among birds). So, migratory songbirds, including the Wood Thrush, need to synchronize their northward movement with the budburst. This means an earlier arrival, according to the calendar, at points all along their migration route.

Wood Thrushes arrive from Central America five days earlier than they did in the 1960s. Research suggests that migratory birds respond to temperature cues along their migration route and speed up (warmer temperatures) or slow down (cooler temperatures). Birds may be responding to temperature directly or indirectly via other temperature-dependent cues such as wind speed and direction and spring leaf out.

Early arrival is not the only adjustment Wood Thrushes are making, however. The birds are also making their nests and hatching young earlier. Wood Thrushes are nesting 24 days earlier than they did in the 1960s. All four of the bird species in the photo above are breeding earlier. Within the web of organisms that supplies food for birds, May 19 of the present feels like June 11 of the 1960s. The earlier nesting in response to a warming climate means birds that normally hatch and rear multiple broods per breeding season, such as House Wrens and Northern Cardinals, may have greater reproductive capacity. PARC research shows that Gray Catbirds and Northern Cardinals are having more young in warmer springs, but other multi-brood species such as House Wrens and Common Yellowthroats are not.

While birds seem to be keeping pace with climate change now, they may not be able to in the future. Their capacity to adjust migratory and reproductive behavioral traits in response to climate change is finite. Also, we’ve already lost an estimated 3 billion North American birds since 1970 due to factors including habitat loss, insect declines, pesticide use, and predation by domestic cats. Now climate change is making bird survival even more difficult. The capacity of bird populations to evolve in response to climate change is also limited – climate change in the Anthropocene is happening much more rapidly than climate change in past epochs, many times faster than evolution can keep up. The good news is we can help birds, ecosystems, and ourselves by taking action to reduce the severity of climate change.

Here are three ways individuals and communities can help birds by mitigating climate change:

1) Conserve habitat: Habitats like forests, wetlands, and prairies provide food and shelter for birds while the plants and soils remove and store carbon away from the atmosphere. These habitats are needed throughout birds’ migratory ranges. Create habitat by reducing lawns and planting native plants. For example, many birds enjoy eating the fruits of spicebush, elderberry, and black cherry, which are native to western Pennsylvania. You can find more bird-friendly plants native to your area at https://www.audubon.org/plantsforbirds.

2) Renewable energy: A just transition to renewable energy sources like properly-sited wind* and solar will reduce greenhouse gas emissions, provide local jobs, improve air quality, and help protect birds and people from climate change. *The National Audubon Society supports properly-sited wind energy.

3) Eat your vegetables: A more plant-based diet is an impactful way to reduce greenhouse gas footprints. Also, choosing food that is grown with less pesticides, and using less pesticides in the stewardship of your garden, helps support the survival of insects that are food for birds. Reductions in demand for pesticides also reduces their manufacture, which further reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Learn more from Project Drawdown.

So get out there, find the signs of spring that are gentle (Trout Lilies) and not-so-gentle (Red-winged Blackbirds), log them in iNaturalist for the City Nature Challenge, and talk with your family and your community about how you can implement one or two (or three!) of the actions suggested above!

You can also read this as an infographic here.

Thank you to the many folks who helped with the development of this blog post and infographic: Luke DeGroote, Mary Shidell, and Annie Lindsay at PARC; the Laurel Highlands network of the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership; Nicole Heller; Taiji Nelson; and Sarah Crawford.

Bonnie McGill, Ph.D. is a science communication fellow for the Climate and Rural Systems Partnership and based in the Anthropocene Studies Section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Teaching About Local Wildlife with the City Nature Challenge

Water Bears: Why My Yard is Like the Moon

Botanists Use Data Collected By Thoreau to Uncover Unexpected Effects of Climate Change

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McGill, BonniePublication date: April 30, 2021