July 1 – September 4, 2023

Presented by The World According to Sound and Carnegie Museum of Natural History

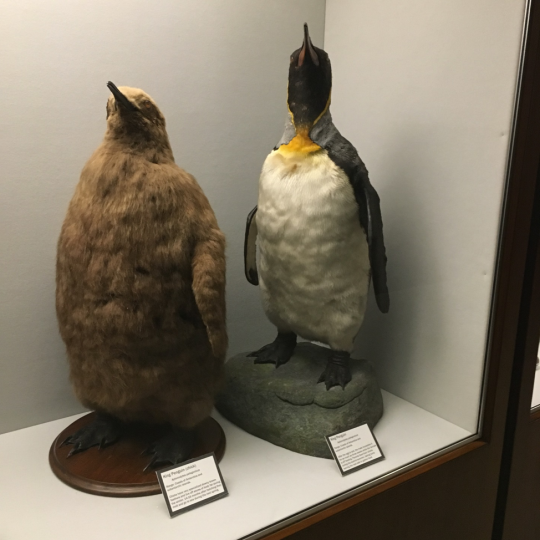

Explore the world with your ears in the new exhibition Chirp, Chitter, Caw: Surrounded by Birdsong. Relax in a listening lounge, mimic unusual bird calls, and stroll down Bird Hall to hear sonic snapshots created by artists Chris Hoff and Sam Harnett—founders of The World According to Sound. Listen to the low rumble of the Southern Cassowary, the Superb Lyrebird mimicking the songs of other birds, and the rhythmic knocks of the Pileated Woodpecker. Tune into the world of birdsong and discover the beauty and complexity of avian communication that surrounds us. Enjoy the museum’s birds like never before.