So you want to take part in the Great Backyard Bird Count? You’ve got your nature notebook ready and you’ve found the perfect spot to birdwatch. What do you do next? The Great Backyard Bird Count website has a lot of resources to help you organize your bird counts and submit your information, so you should check those out before the bird count starts. This post will give you a basic picture of how to document the birds you see and submit your observations properly.

Make a List, Check it Twice

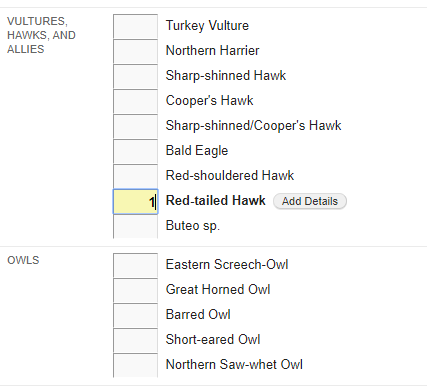

Creating a checklist before you start birdwatching will be really helpful in organizing your research. You can print out this template, enter your location on the count’s website to create a checklist, or create your own guide using a list of birds found in your area. When you enter your observations online, you will submit a “checklist” for each different session of birdwatching. These lists will document where and when you observed, what species you noticed, and how many individual birds you estimated per species. A bird guide like the Merlin Bird ID app can help you identify birds you see.

You will want to make a new checklist for each new day, new location, or new time that you look for birds. For example, you’ll need two checklists if you observe in the same location on two different days, in two different locations on the same day, or in the same location but at two separate times. When you go to submit your observations, you will be asked to enter the location, date, time, and duration of your expedition. You will also be asked whether you were walking, standing, sitting, or even riding in a car while you were counting. Now go forth and count those birds!

Data Ready

Once you have collected your data, all you need to do is go online and enter in the number of birds you saw next to the name of the birds you noticed! You can also add details about each bird species and if you were able to take pictures of any birds, you can include them as well.

Keep in Mind

The submission form will have a question at the end, “Are you submitting a complete checklist of the birds you were able to identify?” which can be confusing to some. You should only click “no” if you are deliberately excluding a species from your list (for example you counted everything except crows).

Explore nature together. Visit Nature 360 for more activities and information.

Blog post by Melissa Cagan.