by Patrick McShea

Today is National Go Birding Day, a designation that prompts questions about how best to become involved in such a do-anywhere activity. As a museum educator, my general advice for anyone seeking to develop bird observational skills is to regularly visit the expansive All About Birds website maintained by The Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

However, when I stop to consider that many potential birders might lack regular internet access, or how my own life-long interest in birds began before I learned to read, alternate approaches gain importance. In light of these circumstances, recent advice from Nick G. Liadis, Avian Conservation Biologist, and founder of the organization, Bird Lab, has universal relevance.

“I almost always start any educational program by asking the question: Did you see a bird today? The answer is almost always ‘yes’ by most of the participants, even children as young as four-years-old. It’s a great springboard into birding/bird-related conversations. It all unfolds from there.”

Nick, whose bird research experience includes past appointments at Point Reyes Bird Observatory in California, and the Museum’s Powdermill Avian Research Center, was explaining the approach he successfully used last summer when he accepted the challenge of presenting the broad topics of birds and bird migration to the 4 – 13-year-old participants in Art in the Garden, a six-week summer camp at the Borland Garden, a community garden and green space in Pittsburgh’s East Liberty neighborhood.

“We’d often talk about a bird’s behavior: If it was singing, where was it perched? Had you seen it before etc. Then I’d talk about how different species have different preferences. Some like living next to people. Some like to be on the tops of trees, and some like to be on the ground etc. This helped to reinforce the beautiful fact that birds are everywhere. That observation really resonates with people.”

Nick borrowed encased taxidermy mounts from the Museum’s Educator Loan Collection for use in some camp sessions, but magazine pictures of birds, field guide images, and especially, the taxidermy mounts of the Museum’s Bird Hall, can also stimulate discussion. Nick simply asked campers to report what they noticed about the preserved birds. “Often their observations were about the feathers. But then we’d talk about the beak and the feet. Those observations helped them to connect the bird to a habitat type or a food preference, and follow-up conversations were about how places as specific as backyards, treetops, or even tree trunks met the needs of some birds.”

A story involving a Zoom call provides anecdotal evidence of how well the birding skills of some campers developed under Nick’s guidance last summer. “One of the kids in the camp was on a Zoom call with his grandparents, who happened to be outside. A red bird flew into view and the kid recognized it as a male Scarlet Tanager! He saw the bird as different from the all-red cardinals. He even noted the black wings.”

Paying attention to the number and variety of birds you notice today is a fine way to participate in National Birding Day. The electronic resources of The Cornell Lab of Ornithology will become more useful after any observations you’re able to make. More birding resources are listed below.

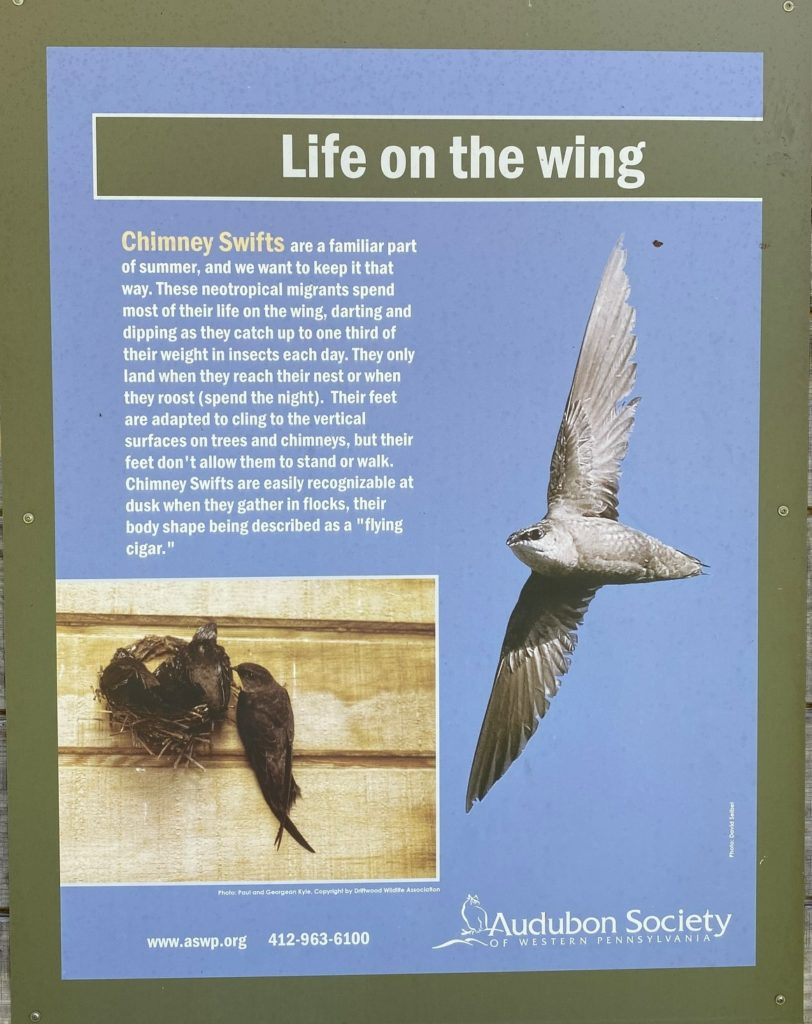

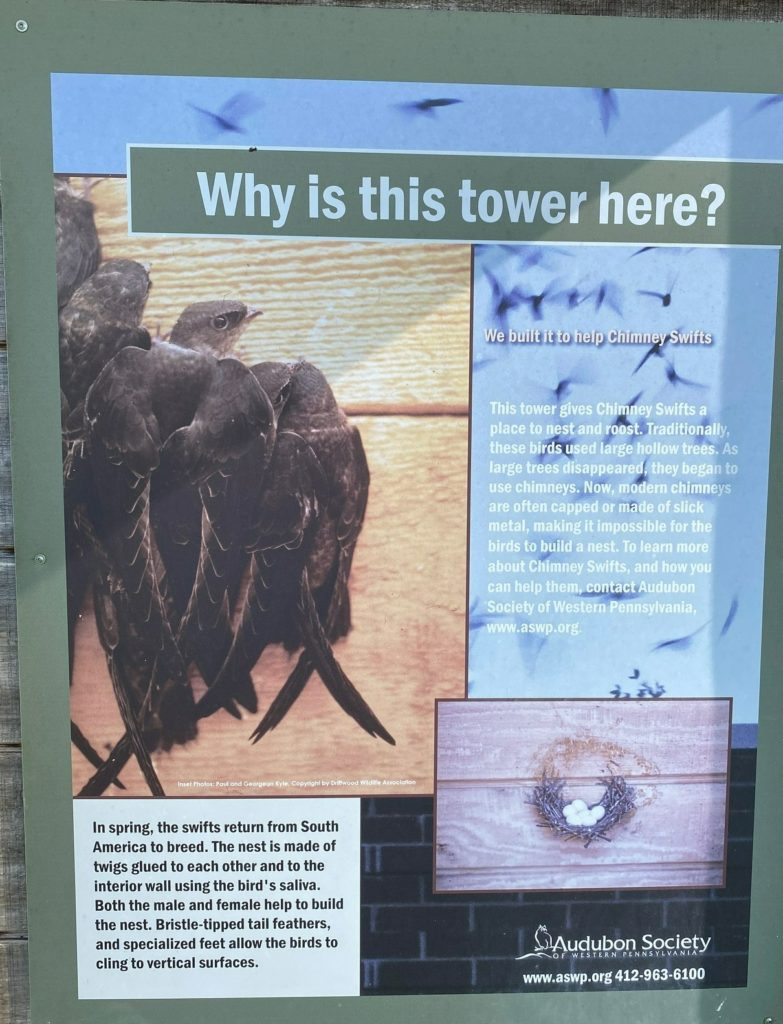

Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania

Patrick McShea is an Educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Using iNaturalist in the City Nature Challenge and Beyond

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: April 29, 2023