by Bob Androw

I was recently asked what my favorite native species of beetle is. A seemingly simple question, but one with no simple answer. I thought first of my primary group of study, the Cerambycidae – the long-horned beetles. But with nearly 1,300 species in North America – which one? Then I pondered the scarab beetles, which I call my “mistress” group – the one I mess around with when the cerambycids aren’t looking. The week before I was asked this question, I was in southern Georgia looking for specimens of an undescribed (new to science) species of scarab beetle in the genus Serica – but while a current priority, I can’t call that my “favorite”.

Then, I remembered the species of long-horned beetle that I looked for in Georgia but did not see. Along a sandy county road, I noticed a lush stand of common elderberry, Sambucus canadensis L. that was in the early stages of blooming. I stopped to check those blooms for any flower-visiting cerambycids and was dismayed to find no insect activity – probably a result of the unusually cool and windy weather.

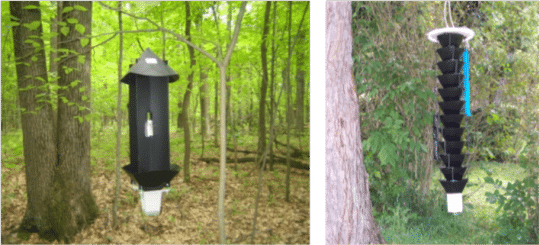

As I was examining the elderberry plants, visions of one of the eastern United States’ more aesthetic species of Cerambycidae flashed into my head – that of Desmocerus palliatus (Forster), or as it’s known by its common name, the elderberry borer. The larvae of the beetle bore in the living pith at the base of the stems. The adults are a beautiful metallic blue with the basal half of their elytra vivid orange. The beetle can be found on elderberry plants, either walking on the stems or clinging to the underside of the leaves. On hot days from May to early July, they can sometimes be found flying around the plants in search of mates.

But, despite a thorough search by squatting low under the plants and looking upward for hiding beetles, none were seen. My timing may have been off for their flight period in that area, the unseasonably cool weather may have delayed their emergence, or there just may not be a population in that particular stand of elderberry.

Image from BugGuide, credit: Chris Rorabaugh, Florida.

Image from BugGuide, credit: James Trager, Missouri

I think that most could agree that Desmocerus palliatus is one of the finest U.S. cerambycids and while not necessarily uncommon, it is just elusive enough to make every encounter a pleasant experience. And I guess that’s reason enough to consider it my favorite – at that moment, in that place…

Bob Androw is Collection Manager of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

The BSF – Leveraging Our Collections and Expertise to Help Fight Invasive Species

Do No Harm: Dealing with Spotted Lanternflies

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Androw, BobPublication date: May 18, 2023