by Nicholas Sauer

I began to think in earnest about industrial melanism while working at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in 2018 when the We Are Nature exhibit was on display as part of the museum’s intensive focus on the Anthropocene. There was an unassuming corner of the exhibit devoted to the fate of the peppered moth (Biston betularia) during the Industrial Revolution. Dark-colored—melanistic—peppered moths were rare in England and Germany until the Industrial Revolution and the inevitable increase of air pollution from the burning of fossil fuels. With the rise of heavy industry, pale peppered moths began to stick out like bright specks on soot-covered vegetation. These pale moths were easy targets for hungry birds. The coal-choked environment favored the moth populations that possessed a gene for darker coloration, providing an example of natural selection at work. In recent years, scientists have located the specific gene that accounts for the darker moths and can trace the changing selection on color variation in peppered moths back to at least 1819 when the burning of coal for industrial purposes began to pick up steam in the British Isles.

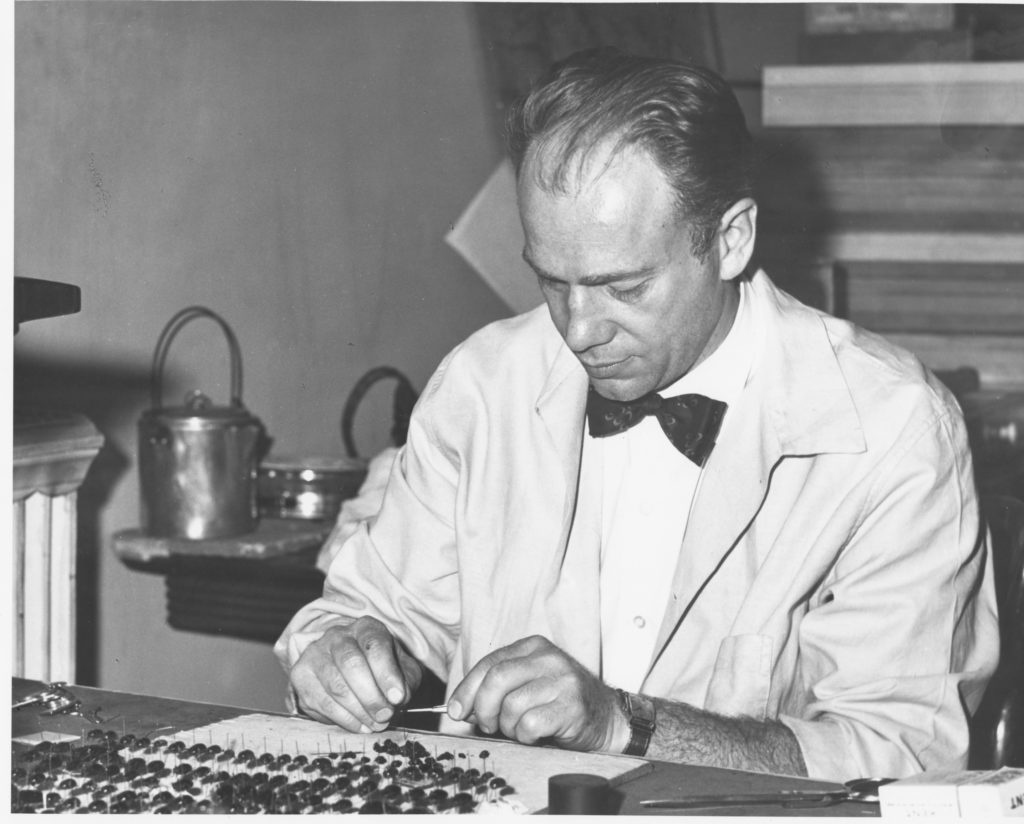

In 1896, English entomologist J.W. Tutt theorized that his nation’s industrial conditions profoundly affected local moth populations. He argued that lichen on trees provided camouflage for the salt-and-pepper-colored moths. According to Tutt, industrial pollution killed off the lichen and, in turn, the pollution—soot and ash—camouflaged the darker moths, particularly the dark form of Biston betularia, f. carbonaria. It was not until the 1950s that Tutt’s theory was tested. Through a series of experiments, lepidopterist Bernard Kettlewell demonstrated that when both light and dark peppered moths (f. typica and carbonaria respectively) were released in industrially-contaminated woodlands in Birmingham and Dorset, England, birds fed on the most “conspicuous” form, f. typica, the pale moths. Kettlewell’s experiment would wind up in science textbooks for decades to come as a demonstration of natural selection.

In the wake of Kettlewell’s findings, similar experiments were conducted in the United States, even in the Pittsburgh area. The scientist leading the melanism study in the Eastern United States in the 1950s, Denis Frank Owen (1931-1996), pored over the moth collections right here at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History as well as those of several other natural history museums in the Northeast and Midwest. A transplant from England at the beginning of his long career as an ecologist, Owen sought to test whether or not Kettlewell’s results would be reflected in his own data on the American side of the Atlantic. Owen’s own findings were very much like Kettlewell’s. This, of course, was unsurprising in the case of Pittsburgh considering the massive amount of pollutants that were emitted by the city’s steel mills. To get a good idea of how polluted the city was at that time, check out the two soot-stained squares that remain on the mural The Crowning of Labor on the second and third floors of CMNH’s Grand Staircase.

Owen discovered that Pittsburgh had some of the earliest records of industrial melanism in the Northeast—melanistic forms of Epimecis hortaria (or, the Tulip Tree Beauty) dating from 1922 and Biston cognataria dating from 1910. Owen posited in his research that the number of melanistic moths were increasing in the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly in environs surrounding industrial cities like Detroit and Pittsburgh, even as far as outlying rural areas. At Westmoreland County’s Powdermill Nature Reserve, all eight of the peppered moths observed in a 1957 study were melanistic, according to Owen.

Unfortunately, records of industrial melanism were never kept as meticulously in the U.S. as they were in the U.K., so our understanding of how widespread the phenomenon was States-side is incomplete. However, since the 1970s, much more data has been collected on peppered moths in the U.S. than before. This data has reflected the implementation of clean air regulations and tracked the overall decline in the ratio of melanistic peppered moths in favor of the pale form, supporting the theory that these moth populations, either Biston betularia (f. typica or carbonaria) or their cousins, are subject to natural selection that is weighted by pollution. Biologist Bruce S. Grant has suggested that more recent data from the post-industrial era be put to greater educational use—not to supplant Kettlewell’s famous experiment, but to supplement it with more up-to-date scientific findings.

Regrettably, even in the “Post-Industrial” era following the birth of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970) and the Clean Air Act (1972), peppered moths are subject to human-exacerbated environmental threats. In the 1980s, when scientists sought an explanation for the continued presence of melanistic moths in rural eastern Pennsylvania, they instead discovered two major dangers to peppered moths and their habitat. First, so-called gypsy moths (Lymantria dispar dispar)—an invasive species introduced to the U.S. by humans in the 19th century—were rapidly defoliating the woodlands that the peppered moths called home. Secondly, the Pennsylvania Department of Forestry was spraying the area with the pesticides Dylox and Dimilin to combat Lymantria dispar and may have adversely affected the peppered moths in the process.

This example of the twin dangers of invasive species and pesticide use, in addition to the earlier instances of industrial pollution, demonstrate human beings’ profound effect on the natural world during the Anthropocene. The travails of the peppered moth are key to understanding the influence humans have on the ecosystems around them, so far as becoming even a variable in the way natural selection operates. The Pittsburgh area and the scientific collections at CMNH have played an important part in the study of industrial melanism in peppered moths and will continue to do so as the natural world responds in its way to human influence. The decline in melanistic moth numbers that correlates with cleaner air and more conscientious environmental regulations provides hope that that human influence is not uniformly negative.

Nicholas Sauer is a Gallery Experience Presenter in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Works Cited

Blakemore, Erin. “New Evidence Shows Peppered Moths Changed Color in Sync with Industrial Revolution.” Smithsonian Magazine, 1 June 2016. <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/new-evidence-peppered-moths-changed-color-sync-industrial-revolution-180959282/>.

Cook, M.L., et al. “Post Industrial Melanism in the Peppered Moth.” Science, no. 3 (Feb 7, 1986): 611. Gale In Context: College, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A4128493/CSIC?u=pitt92539&sid=CSIC&xid=56d31b9d. Accessed 17 Apr. 2021.

Grant, Bruce S. “Fine Tuning the Peppered Moth Paradigm.” Evolution 53, no. 3 (1999): 980-984.

Grant, B.S. and L.L. Wiseman. “Recent History of Melanism in American Peppered Moths.” Journal of Heredity 93, 2 (March 2002): 86-90. <https://academic.oup.com/jhered/article/93/2/86/2187377>.

Manley, Thomas R. “Temporal Trends in Frequency of Melanistic Morphs in Cryptic Moths of Rural Pennsylvania.” Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 42, no. 3 (1988): 213-217.

Maynard, M. and Geoffrey T. Hellman. “Comment.” The New Yorker Magazine, 13 August, 1955: 15. <https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1955/08/13/comment-4365>.

Owen, D.F. “Industrial Melanism in North American Moths.” The American Naturalist 95, no. 883 (Jul.-Aug., 1961): 227-233. <https://www.jstor.org/stable/2458933?seq=1>. Accessed 18 April 2021.

Rudge, David Wyss. “The Role of Photographs and Films in Kettlewell’s Popularizations of the Phenomenon of Industrial Melanism.” Science and Education 12 (2003): 261-287.

Smith, David A.S. “Obituary: Denis Owen.” The Independent, 23 Oct. 1996. <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/obituary-denis-owen-1359897.html>.

Related Content

Incredible Junk Food Diets: Creatures That Clean Up Our World

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Sauer, NicholasPublication date: May 21, 2021