by Amy Henrici

The Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History acquires fossils in a variety of ways, most commonly through field work by Section staff, exchanges with other museums, donations, or (very rarely) purchases. The most recent addition to the collection came by way of a donation.

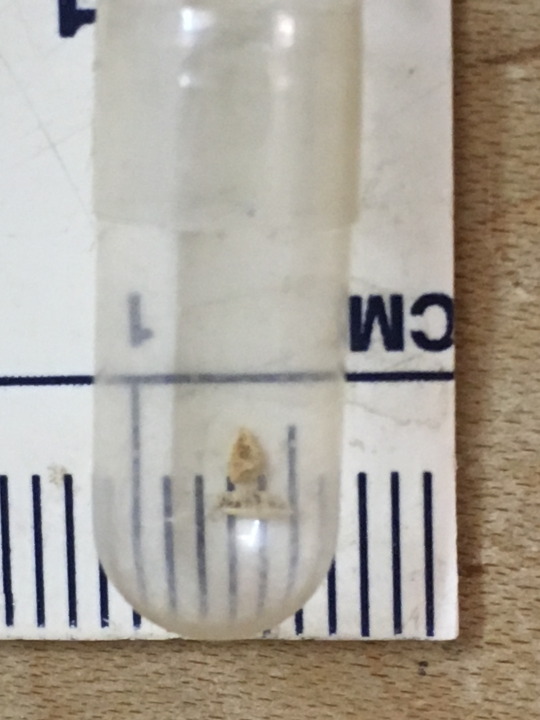

Gary Kirsch discovered the tooth shown above in a sand-gravel bar of a central Ohio stream in 1988 while collecting sediment samples. He had set his sampling equipment on the sand-gravel bar and was moving between the bar and the stream collecting samples. During one of his many forays, Gary noticed an edge of the tooth sticking out of the bar and pulled it out. It was covered in mud, which he quickly cleaned off in the stream to reveal the beautifully preserved tooth, which he identified as that of a mammoth.

Gary recently emailed photographs of the tooth to Assistant Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology Matt Lamanna because he wanted to donate it to the museum. Acceptance of his generous offer required some research: mammoth and Asian elephant teeth are very similar, and because none of the Section staff are experts in fossils of Pleistocene (Ice Age) mammals, we reached out to Pleistocene expert Blaine Schubert at East Tennessee State University, who often uses our collection, to verify Gary’s identification. Blaine was certain that it was a mammoth tooth because an Asian elephant tooth could only have come from a zoo or circus animal, which was highly unlikely. Blaine was curious about how teeth of the two species are distinguished, so he forwarded the photographs to an elephant expert at his university, Chris Widga.

Chris determined that the tooth is the first (forward-most) molar from the left upper jaw, and because it has fairly crenulated enamel, that it is from a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius). Through comparison with tooth eruption and wear schedules (sequences) of modern elephants, Chris concluded that the animal was in its late teens to early 20s when it died. In the wild, modern elephants generally live to about their mid-50s, so this single specimen offers a window into mammoth mid-life.

The Section is grateful to Gary for his thoughtful donation. The specimen will be put on temporary display soon in the PaleoLab window on the first floor of the museum for public viewing.

Amy Henrici is the collection manager for the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.