by Lauren Raysich

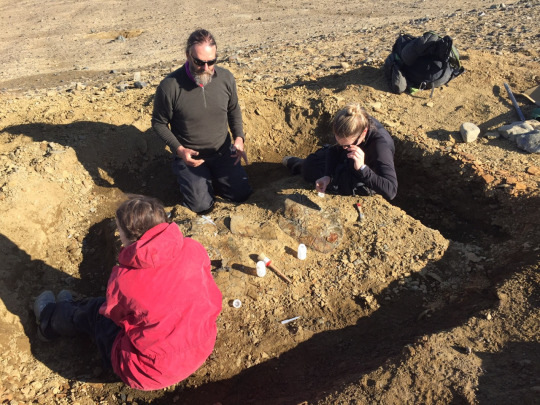

Although many people are familiar with fossilized bones of dinosaurs and other large extinct creatures, some fossils can be so small that a microscope is needed to see them. In Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s PaleoLab, volunteers like me use microscope stations to search for tiny fossils in different sediments collected from sites all over the world. Sediment from the Badwater 20 locality in Wyoming interests me more than any other. Sediment from this site dates to a time known as the Eocene Epoch. The middle of three epochs in the Paleogene Period, the Eocene lasted from 56 to 33.9 million years ago. Many fossils found from the Eocene belong to some of the oldest known members of modern mammal groups. Studying these fossils helps scientists trace the evolutionary histories of mammals we know today.

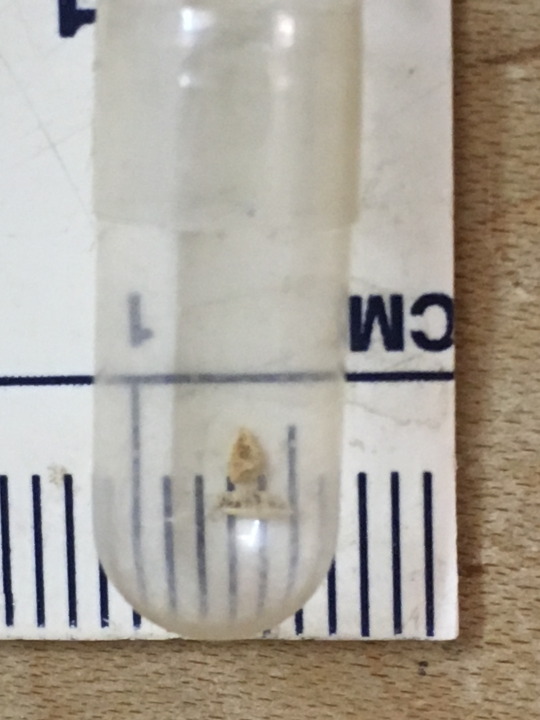

After searching through the Badwater 20 sediment for nearly two weeks, I had found only fragments of bones and teeth. Then, surprisingly, I came across a small, complete bone. It is not common to find complete fossil bones that are this tiny because they can be broken easily, whether by erosion or by being crushed by scavenging animals or water currents. Fossils are not immune to human-induced hazards either. After I found the bone, I was so excited that I accidentally dropped it on the floor of the lab and had to use a magnifying glass to relocate it! (Thankfully, it didn’t break.)

This bone interested me more than any other because it was the first bone I’d found from the Badwater 20 site that wasn’t fractured in some way. Since the bone is so small, I figured it had to have come from a tiny mammal. Through research and the help of other museum volunteers and staff, I have concluded that this bone is a phalanx (finger or toe bone) of an Eocene rodent. The mouse-like animal to which it belonged most likely lived in a tree, a burrow, or the undergrowth more than 37 million years ago! Although, to some people, this little bone may not be as exciting as those of, say, Tyrannosaurus rex, it thus has an important story to tell in the history of life on our planet.

Lauren Raysich is an undergraduate student at the University of Pittsburgh who volunteers in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.