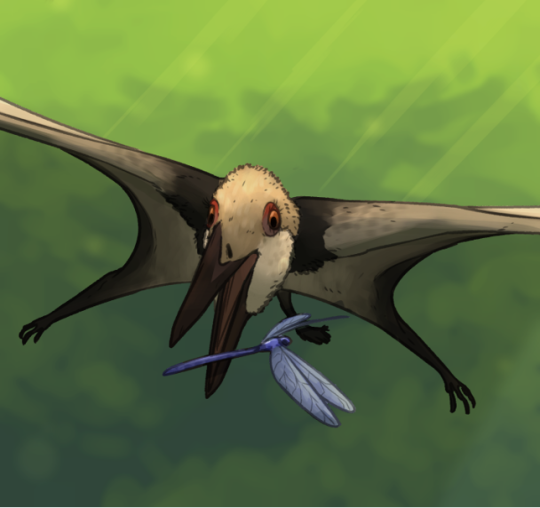

During a mid-March search for a great horned owl nest in an Allegheny County park, a loose jumble of rabbit bones and fur served as a consolation prize. On a mile-long hike that lacked a definitive owl sighting, the rabbit remains were at least evidence of the big winged predator’s recent presence.

Owls swallow their prey whole or in large chunks. After chemical processing within an owl’s stomach separates digestible tissue from bones, teeth, fur, and feathers, these indigestible elements are compressed into a pellet and coughed-up.

The rain-dissected pellet rested on an oak-leaf cushion directly below a 12-foot high trail-crossing branch that might well have been the owl’s cough-up perch. As I imagined a well-fed owl occupying the perch, I recalled a challenge distilled through the wide-ranging conversations of the museum’s recent 21st Century Naturalist Project: How can all who utilize natural history collections routinely summon the imagination necessary to link individual specimens with the environments that once sustained them?

The energy flow represented just by the tiny bundle of white bone and blue-gray fur, for example, ran back in time to the rabbit and all the plant growth that nourished it, and infinitely forward to an owl then incubating eggs of another generation on a hidden nest.

For more information about owl pellets please visit:

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/news/what-are-owl-pellets

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.