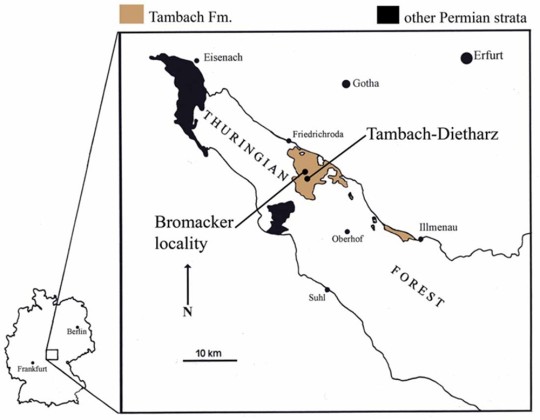

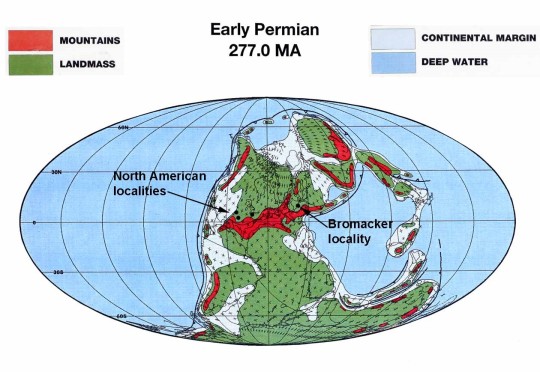

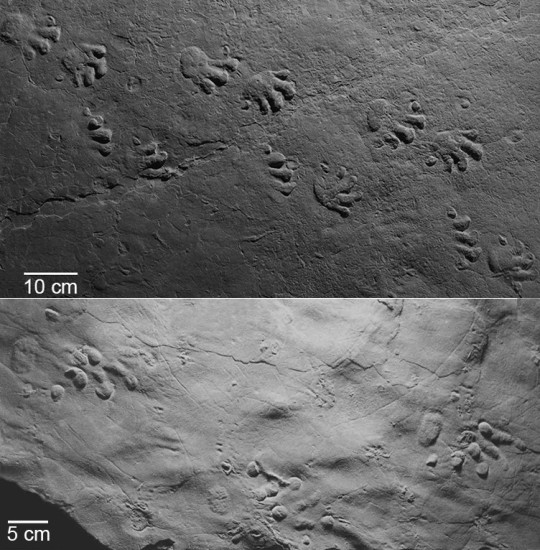

Specimens of two top predators have been discovered at the Bromacker quarry. Like Martensius, both are basal members of the group Synapsida, the later members of which gave rise to mammals. You might be familiar with one of them – Dimetrodon, a synapsid sometimes incorrectly portrayed with dinosaurs, which carried a tall sail on its back that was supported by bony spines. The other is a new genus and species that will be presented in my next post.

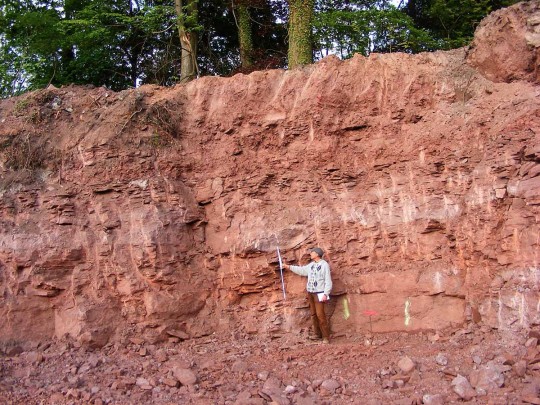

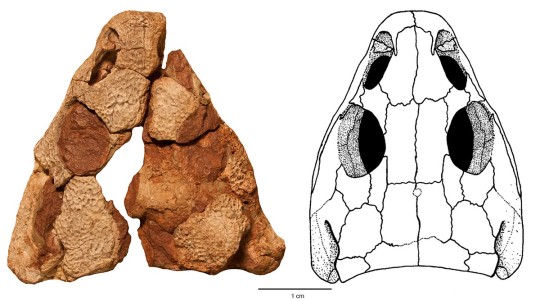

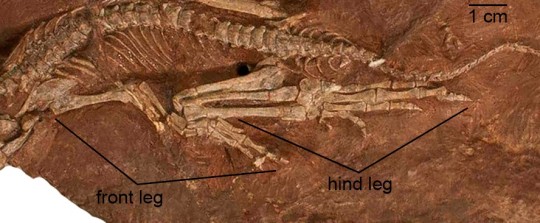

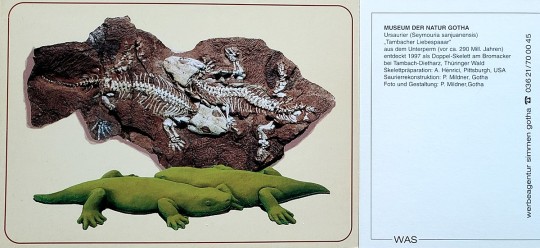

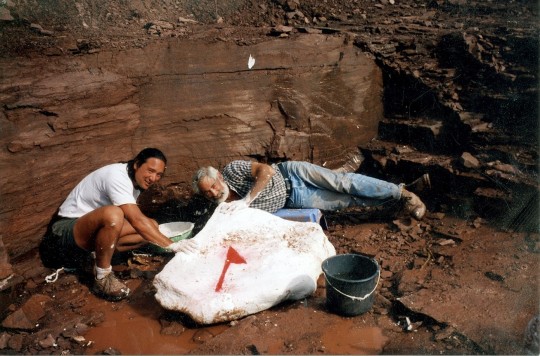

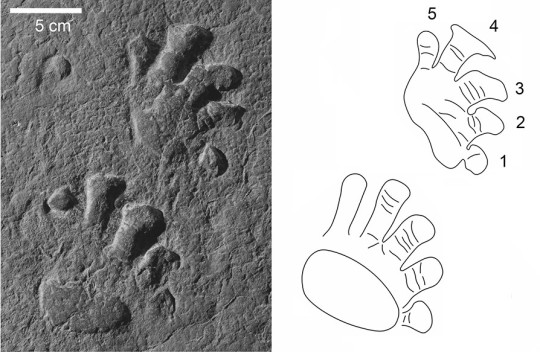

The fossil pictured above, the first-discovered specimen of Dimetrodon from the Bromacker quarry, may not look like much, but it was the first record of Dimetrodon outside of North America. The circumstances under which it was found were very different from the discovery of other fossils from the Bromacker quarry. Before Dave Berman and I arrived for the 1999 field season, Thomas Martens noticed that someone, possibly a fossil poacher, had been in the quarry overnight and knocked some rocks off the quarry lip. The rocks apparently broke upon hitting the ground, which exposed some bones. Thomas carefully picked them up and took them to his lab at the Museum der Natur, Gotha (MNG). When Dave and I met Thomas at the quarry on our first day of the field season, Thomas mentioned the find and told us that he thought the bones were ribs. We didn’t think much of it, other than horror at learning a fossil poacher might have visited the quarry overnight, one of our worst fears.

As planned, Dave and I spent the last day of the field season in the museum collections, and when Thomas let us in that morning, he reminded us to look at the potential ribs and told us where they were. Shortly after we began examining them, Dave and I simultaneously realized that the “ribs” were actually spines of Dimetrodon. We couldn’t believe our eyes, because of all the Early Permian fossils known from North America, Dimetrodon was Thomas’ favorite. Indeed, he’d used an image of it on signs at the Bromacker and included a model of Dimetrodon in a diorama, once on display in the MNG, that showed models of Bromacker animals in their environment. Thomas jumped for joy later that day when we gave him the news.

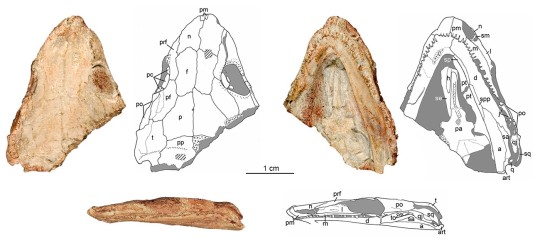

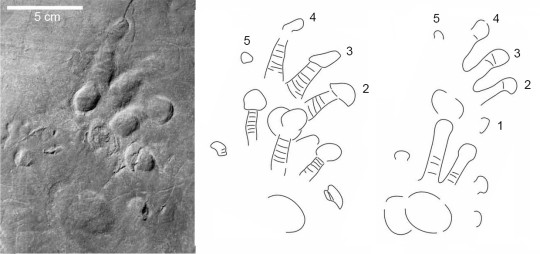

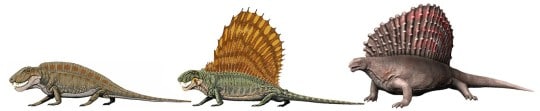

So how did Dave and I so quickly realize that the “ribs” were spines of Dimetrodon? Besides Dimetrodon, some other basal synapsids had sails, the function of which remains unknown, though scientists have speculated they could’ve been used for display or regulating body temperature. The spines (known as neural spines) supporting the sails vary in shape and length, with those of Dimetrodon and its herbivorous relative Edaphosaurus being tall and narrow, and those of another relative, the carnivorous Sphenacodon, being shorter and blade-like. Neural spines of Dimetrodon are easy to distinguish, because in addition to being long they bear fore and aft grooves, which create a dumbbell-shaped cross-sectional outline, and they lack the ‘crossbars’ that occur on the long neural spines of Edaphosaurus. When Dave and I saw the fore and aft grooves, the dumbbell-shaped cross-sectional outline of some broken spine ends, and an absence of crossbars, we knew that the “ribs” were indeed spines of Dimetrodon.

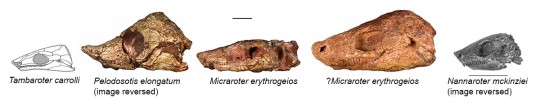

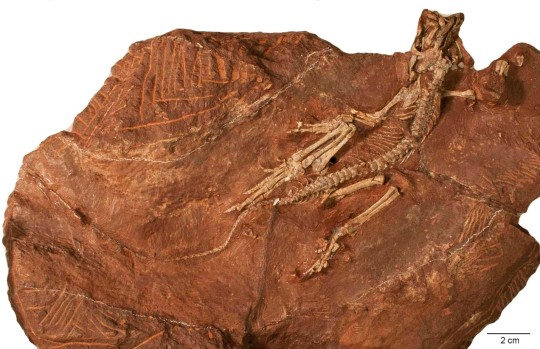

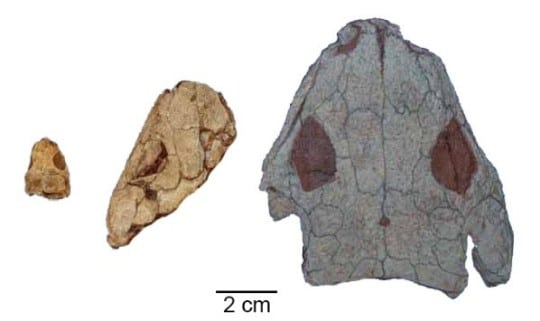

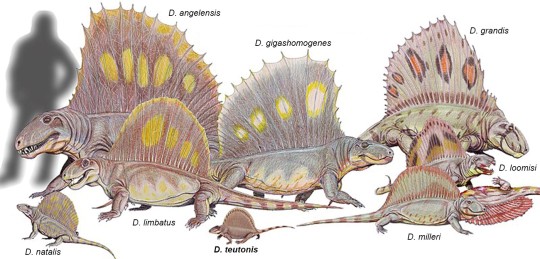

The Bromacker Dimetrodon is considerably smaller than other known species of the genus, and this is one character among other more detailed anatomical features that distinguishes it. For the new species name, Dave selected the Latin “teutonis,” which means an individual of a German tribe, in reference to the geographic origin of the holotype specimen.

Dave was able to use a mathematical equation involving measurements of the vertebrae to estimate the holotype’s weight as a living animal at 31 pounds. In contrast, other known Dimetrodon species have estimated weights of about 81–550 pounds. We later discovered additional partial specimens of Dimetrodon at the Bromacker quarry, and Dave estimated the weight of the largest specimen with vertebrae at 53 pounds, still considerably less than that of what had previously been the smallest species, D. natalis from Texas. Dimetrodon is otherwise known from numerous species from the American mid-continent and southwest that generally got larger through time.

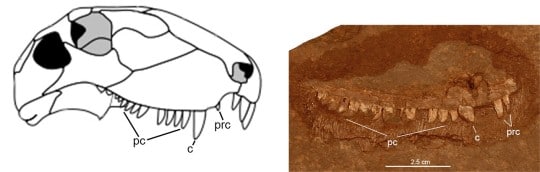

All Dimetrodon species have teeth adapted for meat-eating in being teardrop-shaped with sharp edges for slashing flesh. By size and jaw position these sharp teeth are divided into precanines, canines, and postcanines of varying numbers. Unlike D. teutonis, some species even had fine serrations on their tooth edges. The only known upper jaw bone of Dimetrodon teutonis clearly has two canines, but one is missing and represented by a large gap in the tooth row that would have accommodated this tooth. The second canine is represented only by its broad base, but it too must have been large. Although it was a small animal, the teeth of D. teutonis indicate that it was a meat-eater and as such would have preyed on other vertebrates from the Bromacker, many of which were even smaller.

Stay tuned for my next post, which will be about the second-known apex carnivore from the Bromacker. In the meantime, here are links to scientific papers on Dimetrodon teutonis:

Amy Henrici is Collection Manager in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Keep Reading

The Bromacker Fossil Project Part XII: Tambacarnifex unguifalcatus, the Tambach Executioner