by Suzanne Nuss

I grew up in the silent Canadian Arctic, so sounds switch me to alertness. Once alert, I pause to hear spoken words. During a recent late afternoon in Dinosaurs in Their Time, I focused on a sound that moved me to alertness until it became the voice of the museum’s Gallery Experience Presenter Shannon McGuinn saying, “I found a footprint.”

Because the exhibition hall was mostly empty of visitors, I had been standing near and contemplating the visually striking display of the holotype Tyrannosaurus rex fighting in a field of replica Cretaceous poppies against a cast of another T. rex skeleton, the fossil that since its discovery in 1997 has been known informally as Peck’s Rex. As a Natural History Interpreter, I have been walking these halls for more than six years, yet I had never noticed a footprint. “Hmm,” I thought. “Really?”

I followed Shannon. She pointed. There it was: faint but unmistakable, on the recreated ground surface of the exhibit base, the impressions of three digits resembling a gigantic bird footprint.

We both entertained the same thought: if there’s one track, could there be more? We trotted over behind Peck’s Rex and yes. A second footprint was visible, two feet behind and under the tail, as if the animal had been ambling along.

At this point, Dr. Matt Lamanna, the person most responsible for the scientific content of the now-15-year-old hall, walked by. Gurgling with excitement, we showed him the footprints. He was delighted by our find. “Yes. Two ‘Easter Eggs.’ When Dinosaurs in Their Time was built, we included many simulated footprints, sculpted on the basis of actual fossilized dinosaur tracks. I only wish I’d been able to add a few fake coprolites (fossil poop) too.”

We continued to hunt, with Matt now with us. Three toes again, much smaller. Now that we recognized the tracks as intentional creations, we wondered what animal tracks we might find. Our third discovery, pictured below, was a faux footprint of the bird-like oviraptorosaur Anzu wyliei.

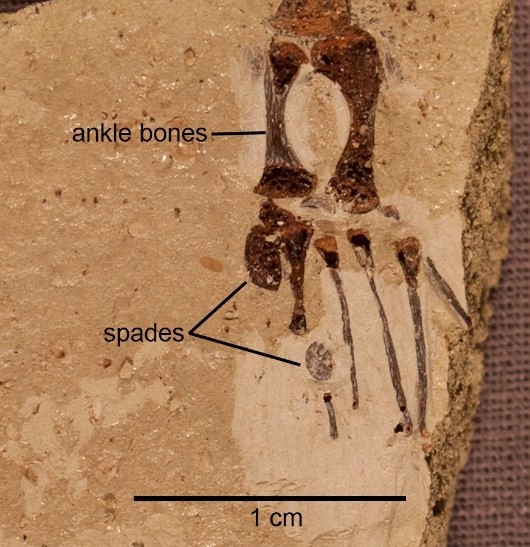

Moving into the Jurassic portion of the exhibition, we stepped back in time, figuratively speaking, by more than 80 million years, and were dwarfed by huge, long-necked, plant-eating dinosaurs (sauropods). We also found very different-looking tracks, some of which were overlapping. Our questions multiplied: could tracks like this indicate that these enormous beasts walked in herds? Is it possible to match up the toes of the foot with the footprint? Was the wide, flat heel of sauropods important for weight distribution?

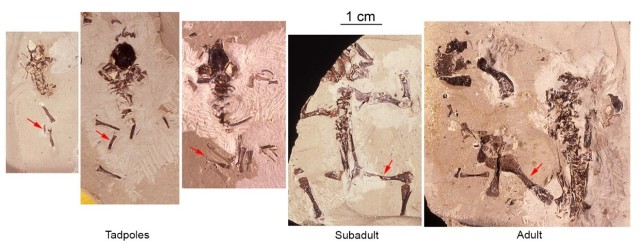

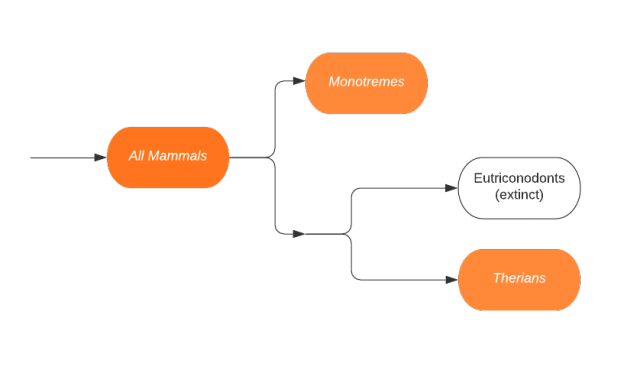

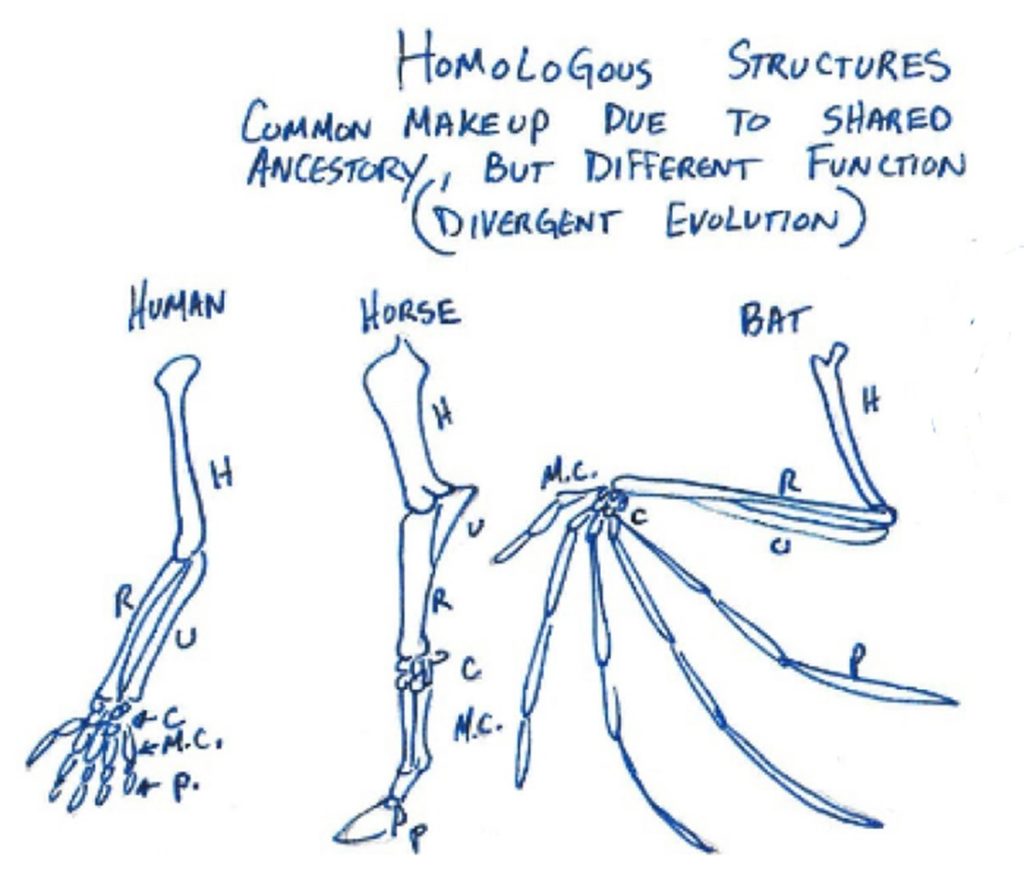

Those thoughts captivated me, mainly because I was introduced to D’Arcy Thompson’s book, On Growth and Form, when I studied biophysics at McGill University in Montreal. One section of the book was devoted entirely to demonstrating how the many kinds of tetrapods (four-limbed, backboned animals such as amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals) all had the same fundamental form: head, torso, and tail, with forelimbs attached at the shoulder girdle and hind limbs attached to the hip. I loved the accompanying images that stretched all the body parts to ‘morph’ one tetrapod into another. A more technical term for this concept is “homologous structures.” In the image below, a simple letter key is used to mark forelimb bones: (H) humerus, (R) radius, (U) ulna, (C) carpals, (MC) metacarpals, and (P) phalanges (the latter better known as finger and toe bones). The hind limbs match up in a similar way.

I thought about what a human footprint looks like, and then a horse footprint, and even a bat footprint. Bears and humans walk with their heels on the ground (a stance known as plantigrade). Horses and giraffes walk on the very tips of their toes (unguligrade), whereas cats, dogs, and predatory dinosaurs such as Allosaurus and T. rex walked on their toes (digitigrade).

Returning to my original spot within the dinosaur exhibition, I was determined to take a closer look. Could I tell from the fossil evidence how the species on display walked? Was it possible to identify the femur, tibia, and fibula of each skeleton?

The colorful murals lining the walls of the exhibition helped. The depictions of each creature are based upon well-studied fossils and biomechanical modelling. I could start musing about how they walked and make a guess. Each guess became a test, which produced a working hypothesis. I have since discovered that the museum’s Bird Hall and Hall of North American Wildlife are also great places to think about feet, footprints, and the biomechanics of animal movement, and why some dinosaur footprints look so much like bird footprints.

Footprints have stories to tell about movement, behavior, and speed. Properly interpreted, footprints can reveal how long their makers’ legs might have been, the width of these animals’ hips, and even whether adults and young traveled together in family groups. What, I have been steadily wondering, would the footprints recording a fight look like?

I don’t want to look anything up yet. I need to muddle through with my own thinking first. When I am ready, I might start with legged robot studies to clarify the physical constraints that must be considered in moving through space. I have since found simulated tracks of Allosaurus and Stegosaurus, and in my searching have also discovered how even an exhibition I know well still holds tremendous potential for inquiry and further learning.

Suzanne Nuss is a Natural History Interpreter at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

The Strange Saga of Spinosaurus, the Semiaquatic Dinosaurian Superpredator

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Nuss, SuzannePublication date: December 19, 2022