by Patrick McShea

As innately land-bound creatures, our comprehension of what goes on in the sky above us is limited. These short-comings are compounded when the sky grows dark. Our disconnection with what amounts to be an adjacent, but largely inaccessible ecosystem, presents a challenge to the organizers of a seasonal project to protect migrating songbirds.

Enormous numbers of birds pass over the Pittsburgh region each year during migration, northbound in the spring, and southbound in the fall. These passages occur during the night, and bright lighting can disorient the migrants’ finely-tuned sense of navigation, sometimes resulting in disabling or fatal window collisions. Lights Out Pittsburgh, is a voluntary program that encourages building owners and tenants to minimize this problem by turning off as much internal and external lighting as possible, nightly from midnight to 6:00 a.m. between September 1 and November 15.

This fall, a group of organizations that includes the Building Owners and Managers Association of Pittsburgh, BNY Mellon, BirdSafe Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership, and the National Aviary announced their participation in the project. Long term, the sustainability of light reduction efforts will require greater appreciation of sky as ecosystem. To that end an essay in Vesper Flights, Helen Macdonald’s 2020 collection of nature writing and personal memoir, provides essential background information.

In “High-Rise” the English naturalist, with Cornell Lab of Ornithology researcher Andrew Farnsworth as her guide, presents the 86th floor observation deck of Empire State Building as a portal for viewing a tiny slice of the northbound spring bird migration high above Manhattan. As Macdonald explains, by referencing the work of another researcher, the lofty vantage point is “a realm where the distinction between city and countryside has little or no meaning at all.”

From Vesper Flights by Helen Macdonald, Grove Press, 2020:

For every larger bird I see, thirty or more songbirds pass over. They are very small. Watching their passage is almost too moving to bear. They resemble stars, embers, slow tracer fire. Even through binoculars those at higher altitudes are tiny, ghostly points of light. I know that they have loose-clenched toes tucked to their chests, bright eyes, thin bones and a will to fly north that pulls them onward night after night. Most of them spent yesterday in central or southern New Jersey before ascending into darkness.

There are, of course, opportunities to make firsthand observations of the passage of migrating songbirds without a skyscraper as viewing platform. As night-flying migrants descend to lower altitudes just before dawn, their presence, numbers, and rough directional movement can be detected from quiet ground-level positions by listening for an irregular cadence of one and two syllable tweets and chips.

In a mid-Twentieth Century essay designed to guide parents in presenting the wonder of nature to their children, the renowned environmentalist Rachel Carson reflected upon this audio evidence of bird migration.

From The Sense of Wonder by Rachel Carson, Harper & Row, 1984 (a renewed copyright from 1956):

I never hear these calls without a wave of feeling that is compounded of many emotions – a sense of lonely distances, a compassionate awareness of small lives controlled and directed by forces beyond volition or denial, a surging wonder at the sure instinct for route and direction that so far has baffled human efforts to explain it.

Some dark early morning this fall, if you’re able to listen to the calls of descending migrants over the background buzz of crickets and the hum of traffic, you’re likely to become a stronger supporter of Lights Out Pittsburgh.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Bird Architecture on Human Infrastructure

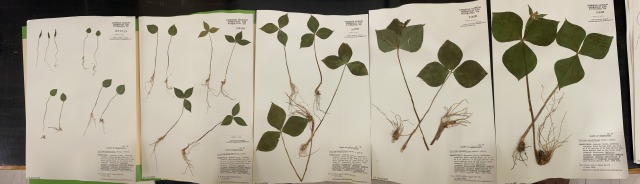

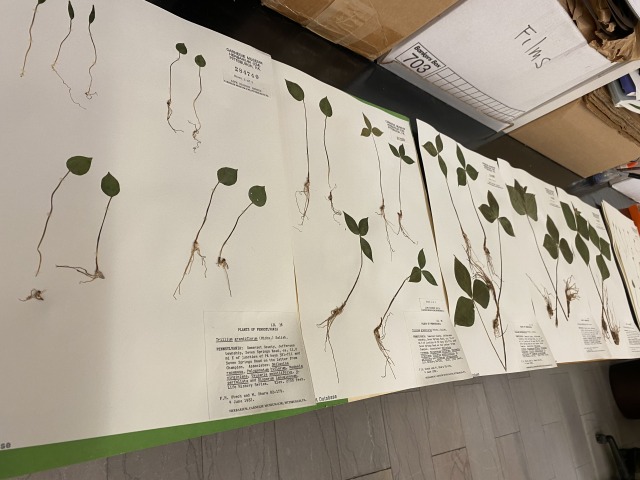

Milestones at Powdermill’s Banding Lab

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: September 21, 2021