Season two out now!

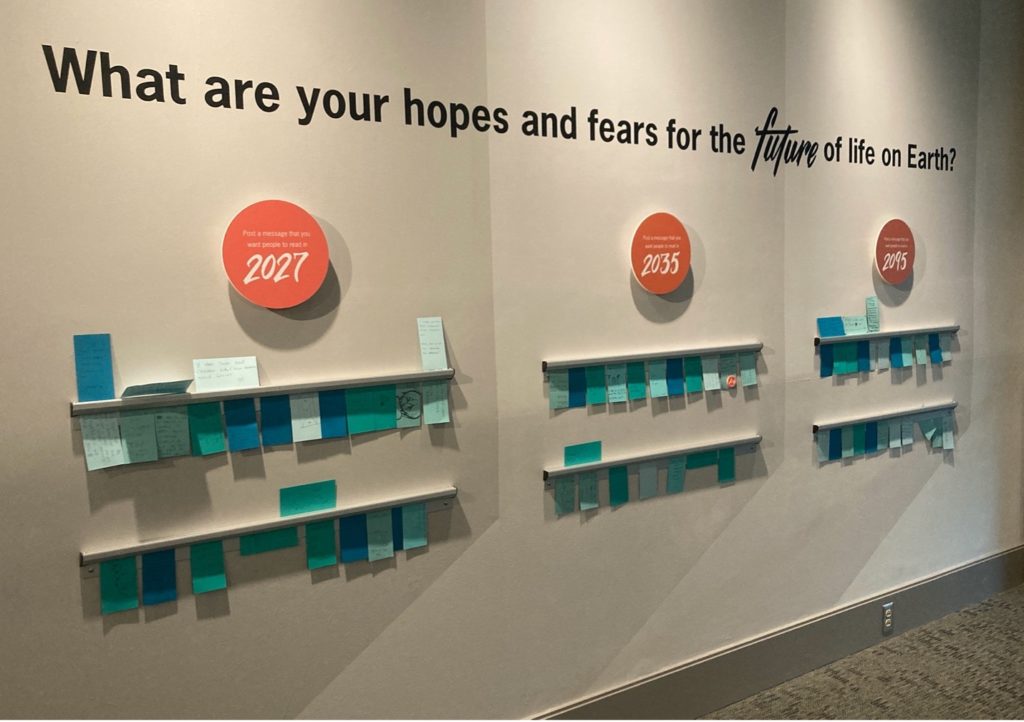

The We Are Nature podcast features stories about natural histories and livable futures presented by Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Host Michael Pisano, a Science Storyteller, and invited guests discuss how humans can create–and are already working towards–a livable, just, and joyous future.

Season one, which premiered in October 2022, centers on collective climate action through 30 interviews with museum researchers, organizers, policy makers, farmers, and science communicators about climate action in Southwestern Pennsylvania. Guests include Radiolab’s Jad Abumrad, US Representative Summer Lee, and Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History Gretchen Baker, among others.

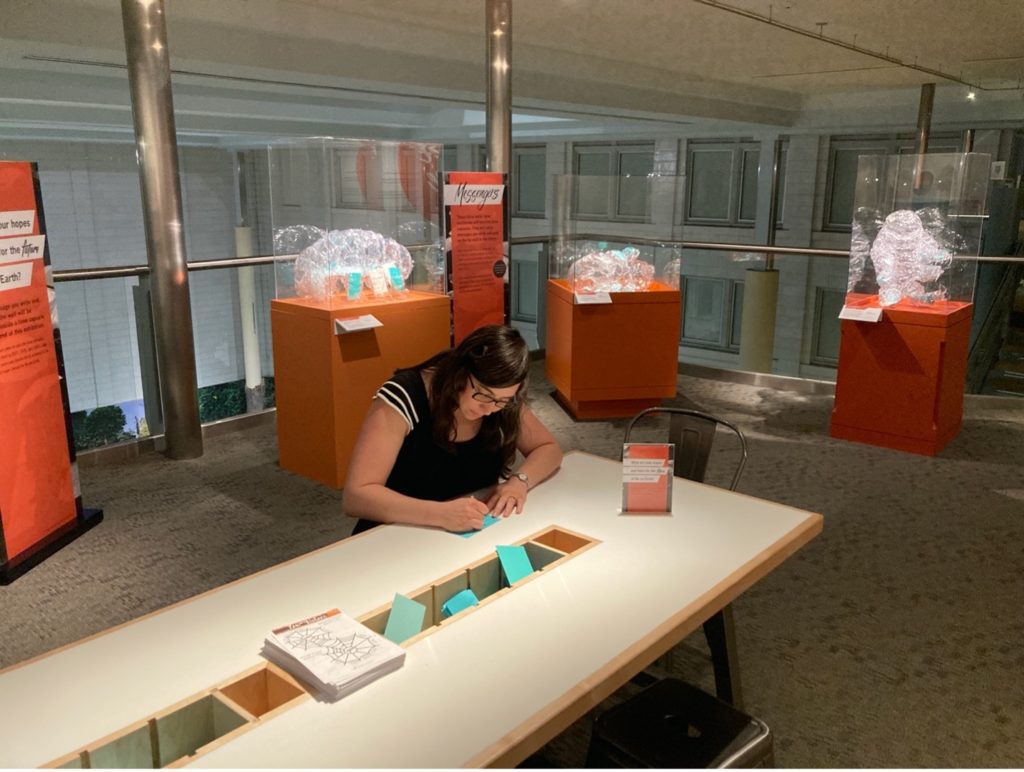

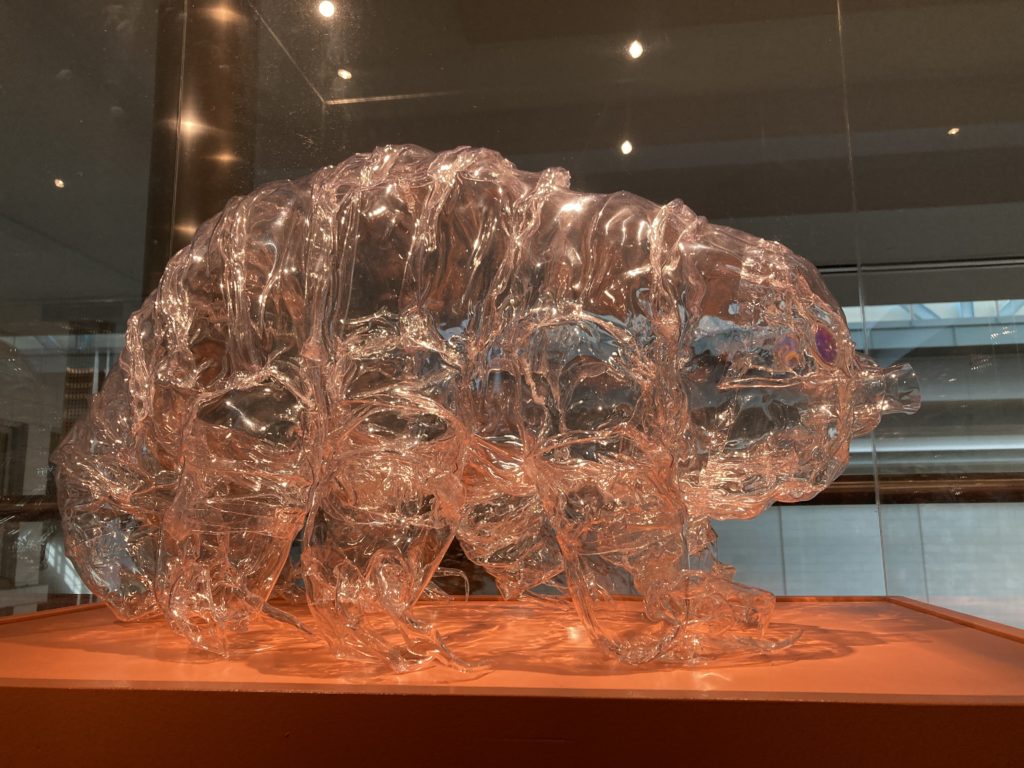

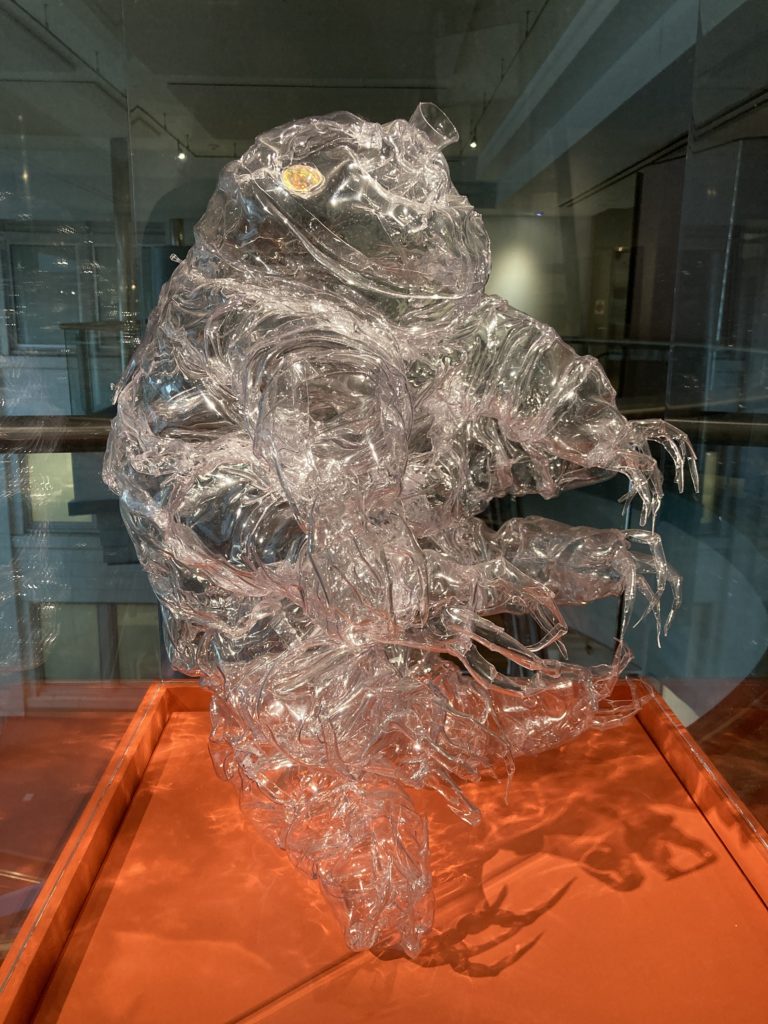

Season two delves deep into Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s collection of more than 22 million objects and specimens. Fourteen Carnegie Museum of Natural History experts as well as special guests from Three Rivers Waterkeeper and the Royal Ontario Museum discuss collection items as windows into the science and ethics of the Anthropocene, a term for our current age, defined by human activity that is reshaping Earth’s climate and environments. What’s more, museum visitors will have the chance to hear clips from and see some of the objects discussed in episodes from season two inside our newest exhibition, The Stories We Keep: Bringing the World to Pittsburgh.

Listen to Season 1 and Season 2 of the podcast below or on major podcast platforms including Apple and Spotify.

Season 1

Episode 1: This is an Emergency, Not an Apocalypse (with Jad Abumrad)

Release date: October 26, 2022

Why is it so hard to talk about climate change without plunging into an anxious doomscroll? How can we change the ways that we talk about the story of life on earth to emphasize hope over despair, and collaboration over competition? Featuring Radiolab’s Jad Abumrad and Nicole Heller, Associate Curator of Anthropocene Studies for Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Bonus Episode: We Can Fix This

Release date: October 31, 2022

A behind-the-scenes chat between Taiji Nelson, Senior Program Manager for the museum’s Climate and Rural Systems Partnership (CRSP) and podcast producer, and Michael about effective climate change communication, plus our goals, hopes, dreams, and terrors for this first season.

Episode 2: Steel City (with Summer Lee)

Release date: November 4, 2022

Why should Pittsburghers care about climate change? What’s happening in our backyard, and how does it connect to the big picture? U.S. Representative Summer Lee joins us to talk about environmental racism, intersectional climate justice, and much more. Host Michael pops in and out with the natural history (and livable future?) of steel.

Episode 3: Carbon and Cattle

Release date: November 11, 2022

Monoculture is messing up the climate. Befriending biodiversity–especially in the soil– can help! Featuring interviews with Michael Kovach (Regenerative Farmer & President of the PA Farmers Union) and Dr. Bonnie McGill (an Ecosystem Ecologist).

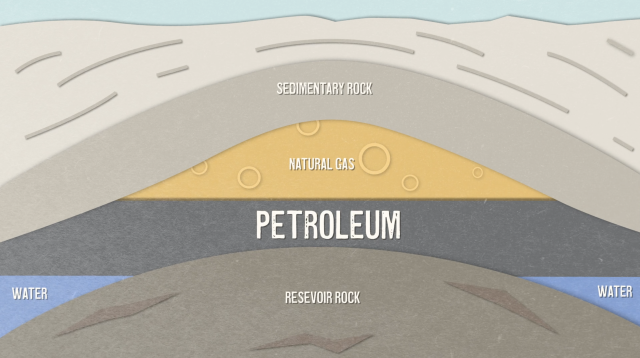

Episode 4: Coal Country

Release date: November 18, 2022

There are less than 5,000 coal jobs left in the state of Pennsylvania, and that number is shrinking. That’s good news for the climate, but what’s next for the commonwealth’s coal communities? Join organizers from the Mountain Watershed Association for insight on building community, protecting public health, and creating new opportunities. Plus, the natural history of coal, water quality watchdogging, and much, much more! Featuring Ashley Funk, Executive Director of Mountain Watershed Association; Stacey Magda, Community Organizer with Mountain Watershed Association; and Eric Harder, Youghiogheny Riverkeeper with Mountain Watershed Association.

Episode 5: Mining and Microbes

Release date: November 25, 2022

Carla Rosenfeld, Assistant Curator of Earth Sciences at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, studies how pollutants and nutrients behave in environments like abandoned minelands, of which Pennsylvania has many. We chat about interspecies collaboration, soil science, the importance of diversity, and much more.

Episode 6: Bridges and Bivalves

Release date: December 2, 2022

Some freshwater mussels can live for over 100 years! During that time, they filter water and improve aquatic ecosystems. Today’s episode is about how aquatic life intersects with the human world. We’ll learn about everything from mussel charisma to climate-proofing infrastructure. Featuring Eric Chapman, Director of Aquatic Science at the Western PA Conservancy.

Episode 7: Food is Nature

Release date: December 9, 2022

Our globalized food system is already feeling the impacts of climate change. Today’s episode shows how decentralizing that food system can help us both be more resilient to extreme weather, and lessen industrial agriculture’s harmful effects. Featuring interviews with urban farmers at Braddock Farms.

Episode 8: Teens in the Wild

Release date: December 16, 2022

By taking care of greenspace, we care for ourselves. Hear about best practices for getting young people involved in land stewardship, and about how fostering a relationship with the outdoors is essential climate action. Featuring Naturalist Educator Nyjah Cephas and two of her students from the Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy’s Young Naturalists program.

Episode 9: Empowerment, Employment, Environment

Release date: January 6, 2023

How are labor and climate related? Today’s episode is all about supporting workers as the climate changes, and about work that supports climate action. Learn about labor history, a just transition, doughnuts and degrowth. Featuring Landforce’s Executive Director Ilyssa Manspeizer and Site Supervisor Shawn Taylor.

Episode 10: Greenways

Release date: January 13, 2023

Tiffany Taulton is a climate policy expert, community organizer, professor of environmental justice, and one of the authors of Pittsburgh’s Climate Action Plan. She joins the show to talk about how our region is preparing for climate change, how that resilience benefits public health, and how climate action can embrace justice and equity.

Episode 11: A Conservation Conversation

Release date: January 20, 2023

Biodiversity is key to our resilience as the climate changes. Our guest today is Conservation Biologist Charles Bier, Senior Director of Conservation Science at the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. Charles has nurtured a deep relationship with Pennsylvanian nature since he was a six-year-old walking around with snakes in his pockets, and has spent his career trying to preserve our wonderful woods, wetlands and waterways.

Episode 12: Bee Kind

Release date: January 27, 2023

Bugs make the world go around. Well, bugs and fungi. And bacteria. And algae. And…ok, it’s all important. We humans rely on many tiny neighbors, and now more than ever, their future relies on us. Come along on a visit to Pittsburgh’s Garfield Community Farm, and travel back to the Cretaceous to learn about the origins of flowers. Featuring the farm’s Community Engagement Coordinator AJ Monsma, youth farmer Israel, and Israel’s friend Tommy the Bee.

Episode 13: We Are the Future

Release date: February 10, 2023

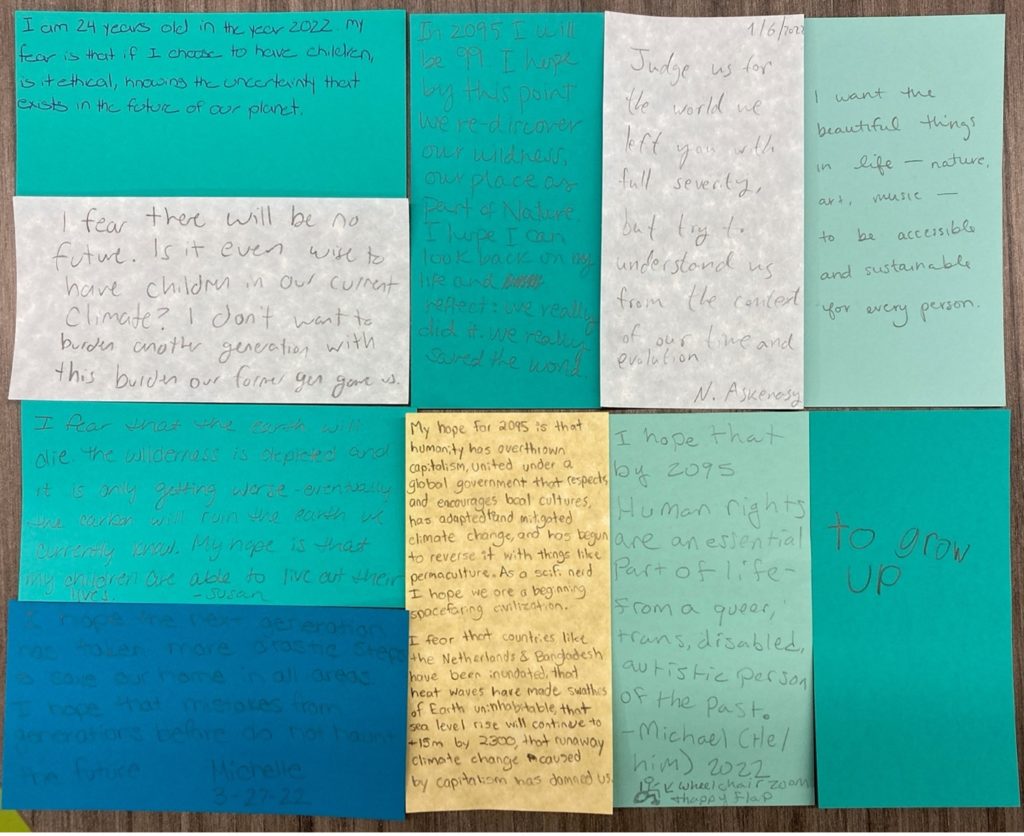

On today’s show, the last episode of Season 1, we look ahead at possible futures. Join us in imagining a planet with space and dignity for all earthlings. Featuring Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Director of Carnegie Museum of Natural History Gretchen Baker, Curator of Anthropocene Studies Nicole Heller, and Educator Taiji Nelson from Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Season 2

Episode 1: A Thin Dusting of Plutonium

Release date: November 7, 2025

What is the Anthropocene, and when might it have started? What is the great acceleration? Can we expect, or engineer, a great deceleration? What can we learn from nuclear history about nuclear futures? Featuring Travis Olds, Assistant Curator of Minerals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Nicole Heller, Associate Curator of Anthropocene Studies at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Encounter Trinitite glass, mentioned in this episode, in the exhibition The Stories We Keep: Bringing the World to Pittsburgh.

Episode 2: Experimental Archaeology

Release date: November 14, 2025

What do we know about the early peopling of our continent and our region? What was the landscape and the climate like then? What can we learn from this natural history about interacting with the land and water today, and moving forward as good stewards? Featuring Amy Covell-Murthy, Archaeology Collection Manager and Head of the Section of Anthropology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Kristina Gaugler, Anthropology Collection Manager at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

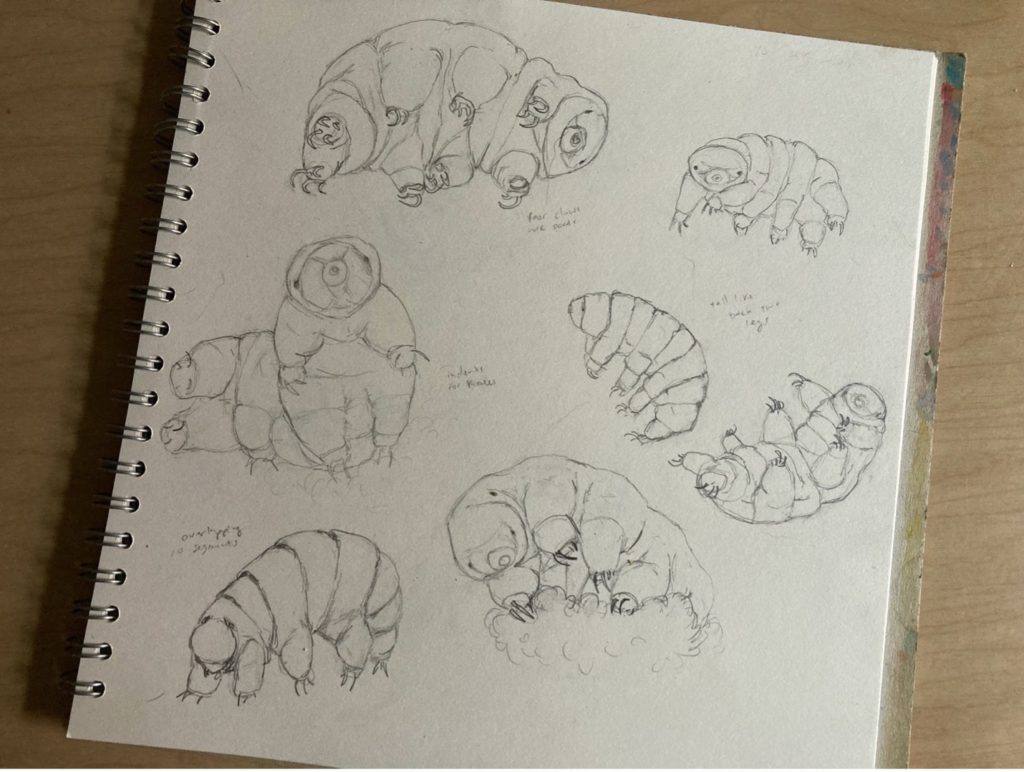

Episode 3: The Institute of Insect Technology

Release date: November 21, 2025

What surprising biodiversity lives alongside us here in Pittsburgh? How can we befriend bugs? What could be awesome about having humans as neighbors? Featuring Ainsley Seago, Associate Curator of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Kevin Keegan, Collection Manager of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Episode 4: Hell Chicken Extinction

Release date: December 5, 2025

What dinosaurs and mammals survived the end of the Cretaceous, and why? What can we learn about resilience from survivors of past extinctions? What can we learn about adapting our culture and cities from the story of evolution? Featuring Matt Lamanna, Mary R. Dawson Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and John Wible, Curator of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Episode 5: Loss in Lutruwita

Release date: December 12, 2025

A second serving of bone banter with two of the museum’s veteran vertebrate virtuosos. How are charisma, colonialism, and extinction linked? What is de-extinction, and will cloning mammoths save the tundra? Featuring Matt Lamanna, Mary R. Dawson Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and John Wible, Curator of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Episode 6: Herbaria for Humanity

Release date: December 19, 2025

How do humans support some plants and endanger others? What do herbaria teach about climate change? How can people and plants collaborate towards livable futures? Featuring Mason Heberling, Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Bonnie Isaac, Collection Manager of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Episode 7: A Real Good Slime

Release date: December 26, 2025

What would a snail scientist do with a blank check? What can we learn from snails and their kin? Why is the ocean getting more acidic, how do we know, and why does that matter? Featuring Tim Pearce, Curator of Mollusks at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Episode 8: Dirty Birds

Release date: January 2, 2026

How does urbanization impact nonhumans? What can we learn from Pittsburgh’s past and present air quality challenges? How do we make space for biodiversity in cities? Featuring Serina Brady, Collection Manager of Birds at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Jon Rice, Urban Bird Conservation Coordinator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Episode 9: Jar of Frogs

Release date: January 9, 2026

Why is the museum hoarding alcoholic pickle jars? What kinds of research are made possible by the museum’s herpetology collection? How are organisms changing because of climate change, urbanization, and other anthropogenic pressures? Featuring Jennifer Sheridan, Associate Curator of Amphibians and Reptiles at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Encounter frog specimens from Borneo mentioned in this episode in the exhibition The Stories We Keep: Bringing the World to Pittsburgh.

Episode 10: A Very Important Popsicle

Release date: January 16, 2026

What can we learn from lakes about livable futures? How can people in the Anthropocene find optimism and be moved to climate action? Featuring Soren Brothers, the Allan and Helaine Shiff Curator of Climate Change at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Episode 11: Pellets, Pellets Everywhere

Release date: January 23, 2026

What are plastics and how are they made? How do they get into our waterways? How do novel materials like plastics define the age we live in? What materials might replace them? Featuring Nicole Heller, Curator of Anthropocene Studies at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and Heather Hulton VanTassel, Executive Director of Three Rivers Waterkeeper. Encounter nurdles, small plastic pellets, mentioned in this episode in the exhibition The Stories We Keep: Bringing the World to Pittsburgh.

Credits

Host, Writer, and Editor: Michael Pisano

Assistant Editor: Garrick Schmitt

Audio Recording: Matthew Unger and Garrick Schmitt

Voice Talent: Mackenzie Kimmel

Music: DJ Thermos

Producer: Nicole Heller

Producer: Sloan MacRae

Producer and Co-host (season one): Taiji Nelson

Field Reporters (season one): Di-ay Battad, David Kelley, and Jamen Thurmond