by Mason Heberling

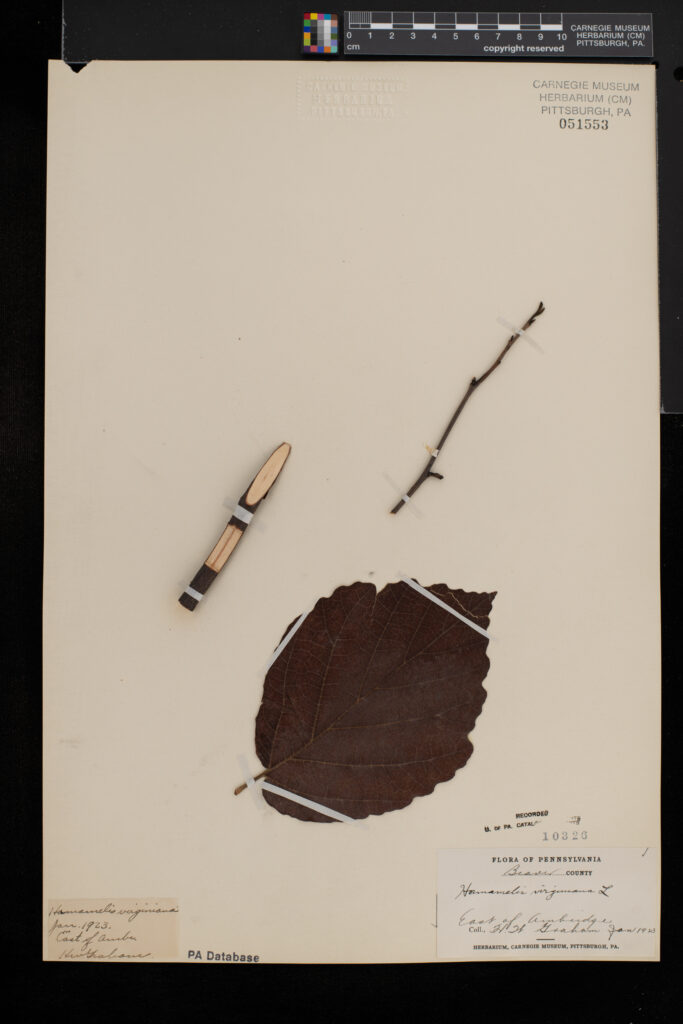

This specimen of common witch hazel (Hamamelis virginiana) was collected in January 1923 in Beaver County, Pennsylvania “East of Ambridge” by H.W. Graham. Herbert W. Graham (1905-2009) was an “Assistant” in Botany at the Carnegie Museum from 1925-1929 while he was a student at the University of Pittsburgh who later became an oceanographer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. During his time at the museum, he collected many specimens, often with his brother, Edward H. Graham, who was also an Assistant in Botany, later curator (1931-1937) and later, a well-known conservationist with the US Department of Agriculture. The Graham brothers went on expeditions to the Sonoran Desert in the late 1920s, collecting specimens and information that was used to create the desert diorama that remains in the museum’s Hall of Botany today.

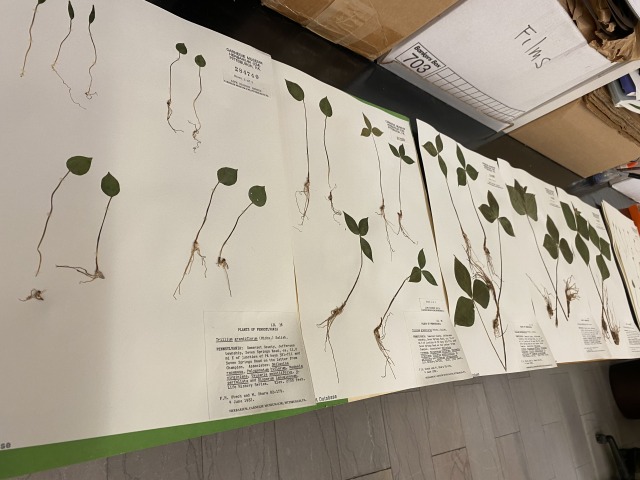

This specimen has a “bits and pieces” feel to it, but shows what the plant looks like in winter, with branches, buds, a leaf, and even including a nice cross section cut out of the stem. The leaf is in great shape, which makes me question whether the leaf was truly was collected in January, when the leaves are usually dry and crumbled from the wrath of winter.

The specimen was simply collected in “January 1923” with no note on the day of year. I feel that coming off a holiday break (what day is it?). But more seriously, it reminds us that many specimens of the past were collected for different purposes with many of their uses today unanticipated. For instance, collectors today would certainly record the calendar date of collection, valued just as much as information on the location it was collected, as scientists routinely use specimens to date information to understand the seasonal timing of leafing, flowering, and fruiting with changing environmental conditions over time.

The leaf is a nice touch, too. It indicates that at least some leaves were still around in the winter of 1923, and it is quite possible they were even still connected to the stem. Though this species is deciduous (drops its leaves seasonally), common witch hazel has been known to sometimes hang onto some dead leaves on branches through winter. This phenomenon is known as “marcescence.” Why this happens isn’t fully known. Read more here.

You can find this specimen and 588 others of the species in the Carnegie Museum herbarium here.

Above: Witch hazel exhibiting marcescence, with last year’s leaves still attached in early spring (photo taken March 23 2021 at Powdermill Nature Reserve)

Below: Witch hazel’s magnificent autumn blooms. Unlike many woody plants in our region that bloom in spring as leaves are emerging, this species blooms in fall, as its leaves are dropping! (Photo taken October 29 2022 in New Kensington, PA.)

Mason Heberling is Associate Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Witch Hazel Collected on Halloween in 1931

Collected On This Day in 1951: Bittersweet

What’s in a Name? Japanese Knotweed or Itadori

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Heberling, MasonPublication date: January 16, 2024