Vampires, creatures of folklore that feed on the lifeforce of the living, have long fascinated us. Many cultures have their own version of how vampires behave and are repelled by many different things. Modern vampires in movies, TV shows, and books have some similar main characteristics—let’s explore some interesting or common beliefs about vampires and where they may have come from.

Garlic

It’s a common belief that garlic repels vampires, but did you know that some of that belief is grounded in fact? Garlic, specifically the chemical compound allicin inside garlic, is a powerful antibiotic. Some European beliefs around vampires stated they were created by a disease of the blood, so a powerful antibiotic would “kill” a vampire.

An actual disorder of the blood, porphyria, may also be an origin for this belief: porphyria can cause those who suffer from it to look pale and even make their teeth look bigger because their gums shrink. Garlic makes these symptoms worse, so people with porphyria would often avoid it—making others around them believe they were vampires.

Mirrors

Vampires avoiding mirrors is a more recent belief— the first known reference to this is from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which was published in 1897. But why wouldn’t a vampire show a reflection?

There are a few reasons that this belief may exist. Mirrors were traditionally backed with silver (and some still are today). Silver was commonly believed to repel evil spirits, possibly because it has antimicrobial properties; so, much like garlic, the healing properties may be what was supposed to scare off a vampire.

Another reason that suspected vampires may have avoided mirrors is because of the changes to their appearance from diseases commonly confused with vampirism, porphyria and rabies. People afflicted with these diseases may have avoided looking in a mirror for that reason, causing others to assume that “vampires” avoid mirrors.

Counting

Why does Count von Count, a vampire, teach us how to count on Sesame Street? It comes from a European belief that vampires are compelled to count spilled seeds or grains. Some Slavic coastal towns also believed that vampires would count the holes in a fishing net. It was common practice to scatter seeds outside the entrances to a home (or drape fishing nets over them). Some Chinese myths say that a vampire must count every grain if they come across a bag of rice. A vampire would stop to count, delaying them until sun-up, and we all know that vampires don’t do well in sunlight.

A common seed used was mustard seed, which was also known as eye of newt!

Now that we’ve learned a little about fictional vampires, let’s explore some real-world vampires!

Vampire Ground Finch

The Galapagos Islands are home to many unique and unusual species, so the vampire ground finch fits in well. This species of sharp-beaked finch lives on Darwin and Wolf Islands, and like most other finches it feeds primarily on seeds. However, seeds can sometimes be a limited resource, so vampire ground finches supplement their diet by eating small amounts of nutrient-rich blood from Nazca or blue-footed boobies.

It is believed that this behavior developed because the finches were first eating ticks from the bodies of other birds, which steadily transitioned into them eating small amounts of blood. Believe it or not, the other birds don’t seem to mind the vampire ground finches doing this, and don’t try to stop them!

Vampire Bats

There are three species of bats that survive by exclusively feeding on the blood of other animals- the common vampire bat, the hairy-legged vampire bat, and the white-winged vampire bat. All three species are found in Central and South America.

Like other bats, they hunt at night and rely on echolocation to find their prey, which is typically sleeping livestock, like cows. Vampire bats use their sharp teeth to make a little cut and then lap up the blood. It doesn’t hurt the animal they’re feeding from, in fact most animals don’t even notice it happening and stay asleep! These bats occasionally try to feed off humans, but it is very rare.

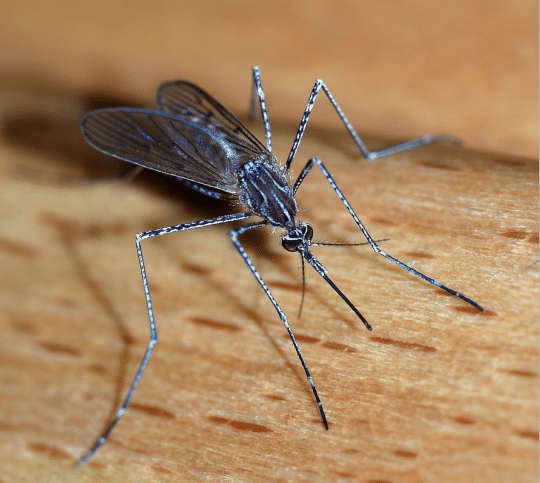

Mosquitos & Ticks

We’ve all felt the aftermath of an itchy mosquito bite! Mosquitos feed on blood from humans and other animals, but it’s only female mosquitos that eat blood. Female mosquitos need the protein from blood to produce eggs, and male mosquitos don’t so they feed on plant nectar.

Ticks drink the blood of both warm and cold-blooded animals, latching on and feeding slowly over several days. They can fast for a long time between meals, but do need to feed on blood as they progress through the stages of their life cycle.

Neither mosquitos nor ticks (or any other blood eating insects) eat enough blood to be dangerous to humans. The biggest danger is that these insects can carry diseases, so make sure to properly care for and clean any insect bites, and see a doctor if necessary!

Jo Tauber is the Gallery Experience Coordinator for CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department, as well as the official Registrar for the Living Collection. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Booseum: Spooky Coloring Pages