by Lindsay Kastroll

Once again, spring has sprung. Prepare to see the gorgeous forests of Pennsylvania launch back into action. I, for one, can’t wait to get outside and explore as the weather continues to improve. I was recently reminded of the fact that Pennsylvania is home to two species of flying squirrels, and I am definitely adding them to my list of things to see. But of course, this is Mesozoic Monthly, so flying squirrels can’t be the stars of this article. Instead, the superficially flying squirrel-like “ancient gliding beast” Volaticotherium antiquum is stealing the spotlight!

Although Volaticotherium was about the size of a modern flying squirrel at 5–6 inches (13–15 cm) long, it belonged to a group of early mammals called eutriconodonts that includes some of the largest mammals that lived alongside non-avian dinosaurs. “Eutriconodont” means “true three-coned tooth,” in reference to the three longitudinally aligned cusps on their molars. Although not all mammals today have three-cusped molars, the ancestors of modern mammals did. Does this mean that modern mammals evolved from a eutriconodont? The answer is no, though they did evolve from a mammal with eutriconodont-like teeth.

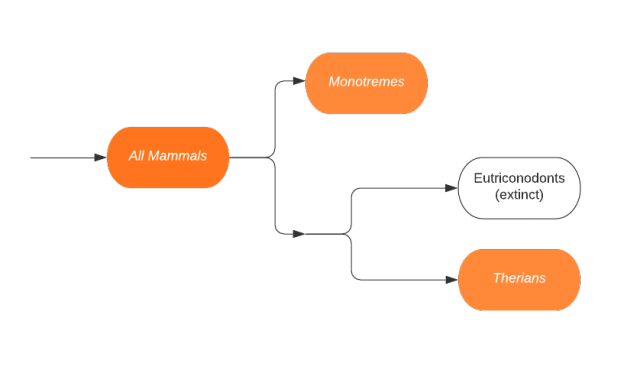

We can split modern mammals into two main groups: the monotremes, which are egg-laying mammals like the platypus, and the therians, which include both marsupial and placental mammals (like kangaroos or humans, respectively). The ancestors of monotremes diverged (meaning, formed their own ‘branch’ of the evolutionary tree) before eutriconodonts and therians evolved. Eutriconodonts and therians share a different, more recent, and as-yet unknown common ancestor. Monotremes, therians, and eutriconodonts actually lived alongside one another for over one hundred million years before eutriconodonts became extinct near the end of the Cretaceous Period (the third and final division in the Mesozoic Era, or ‘Age of Dinosaurs’).

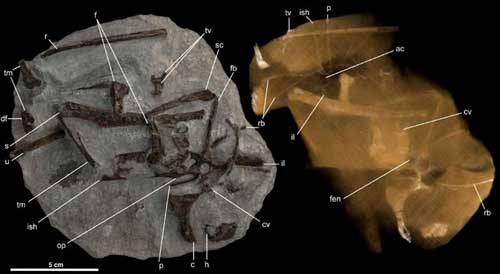

The canines and molars of eutriconodonts were pointy, suggesting that these mammals were carnivores or insectivores. Volaticotherium is no exception, which makes it particularly unique, as most other gliding mammals are herbivores! Because it was so small, Volaticotherium was probably an insectivore, but a larger cousin, Jugulator, could probably eat small vertebrates. As an arboreal glider, Volaticotherium could soar from tree to tree to catch insects in midair. Instead of wings, it had a patagium, a broad flap of skin that stretched between the fore- and hind limbs, creating enough surface area to achieve gliding descents. The various limb adaptations necessary to make Volaticotherium an efficient glider also made it poor at maneuvering on the ground. It can be hard to understand why an animal would evolve features that would hinder its terrestrial movement, and multiple hypotheses have been put forth to try to explain this. Most of these focus on the benefits of leaping out of trees to escape predators or to quickly traverse territory between arboreal food sources, scenarios based on herbivorous mammals. Because Volaticotherium was a gliding predator, perhaps gliding conferred other advantages to this eutriconodont.

The fossilized remains of Volaticotherium were found in a layer of rock called the Daohugou Bed in China. This deposit consists of lakebed sediment and volcanic ash compacted into solid rock over millions of years as more heavy sediment was deposited on top of it. There is a debate about how old the Daohugou Bed is, but most estimates place it near the middle or end of the Jurassic Period (the middle period of the Mesozoic). Getting the timing right is important. Because Volaticotherium is among the oldest known gliding mammals, its discovery pushes the origin of mammalian gliding back as much as 70 million years earlier than previously thought!

A variety of factors have led geologists to struggle in determining the age of the Daohugou Bed. In an ideal geologic record, rock layers would be perfectly horizontal, creating a continuous stack with the oldest layers on the bottom and the newest layers on top. However, this is rarely the case. Sediment may be eroded before new layers are deposited, creating a gap of time without record in that sequence of rocks. This phenomenon, where two rock layers do not represent a continuous progression of time and have a gap of data missing between them, is called an unconformity. Other issues with dating rock layers involve the squeezing, stretching, folding, melting, and chemical alteration of rock layers when they’re subjected to geologic processes. These forces can result in old rock layers being placed on top of younger ones, making it hard to determine the actual sequential order of the rocks. Changes can also occur within the minerals that compose the rocks, making radiometric dating much more difficult.

The Daohugou Bed has an unconformity above and below it, and it has been folded, which makes attributing an exact age to it that much harder. When you go out hiking in the beautiful spring weather on the horizon, take a moment to look at the rock outcrops you pass and think about what those layers might have experienced on their journey to where they are today. And if you continue your hike after sunset, be sure to keep your eyes peeled. If you’re lucky, you might just catch a glimpse of a flying squirrel gliding through the forest!

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Mesozoic Monthly: Nasutoceratops

Researchers Announce Surprising Clue in the Evolution of the Mammalian Middle Ear

Ah, Snap! Dino Named for Marvel’s Thanos

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Kastroll, LindsayPublication date: March 31, 2021