by Pat McShea

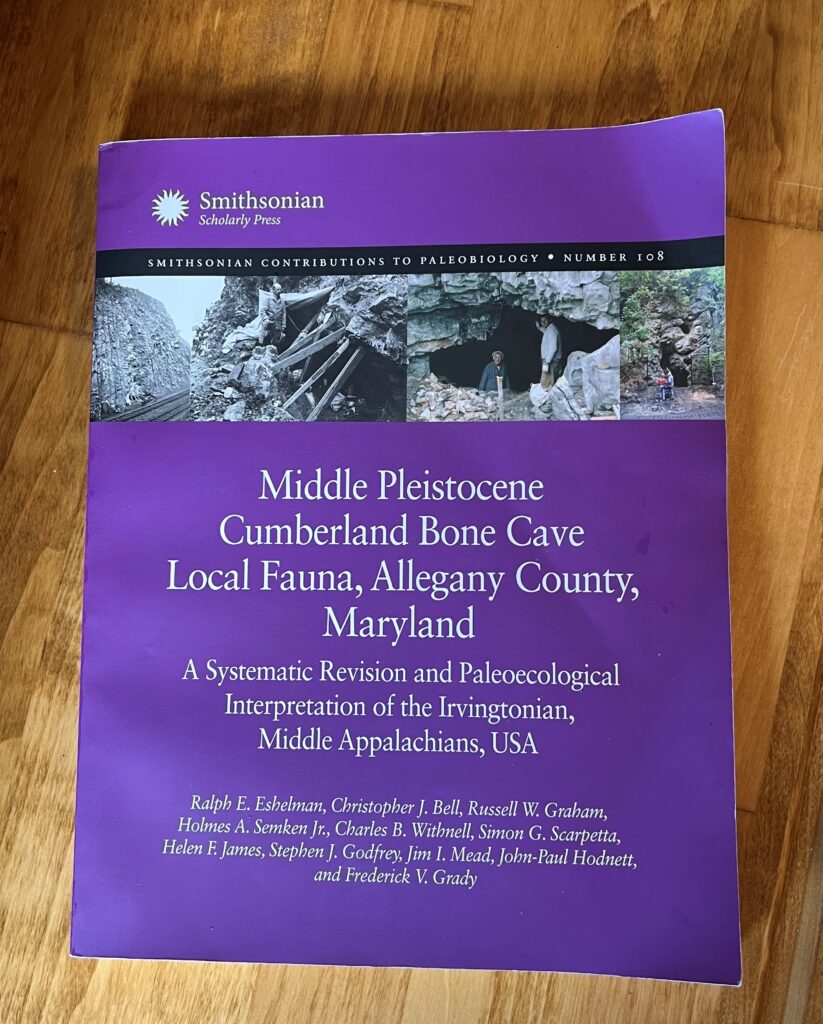

For paleontologists who specialize in interpreting fossil evidence from the Pleistocene, deposits in some Appalachian caves offer windows into the period of the past commonly referred to as the Ice Age. A recent Smithsonian Scholarly Press publication summarizing the discovery, collection, preparation, and interpretation of fossils from a cave in western Maryland strongly supports the window-into-the-past metaphor. The 305-page volume, a product of eleven co-authors, bears the long descriptive title, Middle Pleistocene Cumberland Bone Cave Local Fauna, Allegeny County, Maryland: A Systematic Revision and Paleoecological Interpretation of the Irvingtonian, Middle Appalachians, USA. Remarkably, this chronicle of fossil collecting expeditions mounted by five different organizations over more than a century is dedicated to John Edward Guilday, a Curator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History from 1951 until 1982, and the field crew of museum staff and volunteers who for decades assisted his research efforts.

The collective nature of knowledge presented in the publication makes the dedication particularly appropriate. The fauna list for the site’s vertebrate fossils alone includes 109 creatures ranging in size from mole to mastodon, and the deposition of these remains, over a period of several thousand years, happened more than 700,000 years ago. Deciphering information from such a rich fossil assemblage requires a detailed understanding of other fossil-rich caves, and Guilday’s deep knowledge of findings from sinkholes in Pennsylvania and caves in Tennessee, Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia, enabled him to recognize and interpret evidence for such past regional events as range extensions and contractions for various species and repeated changes in climate.

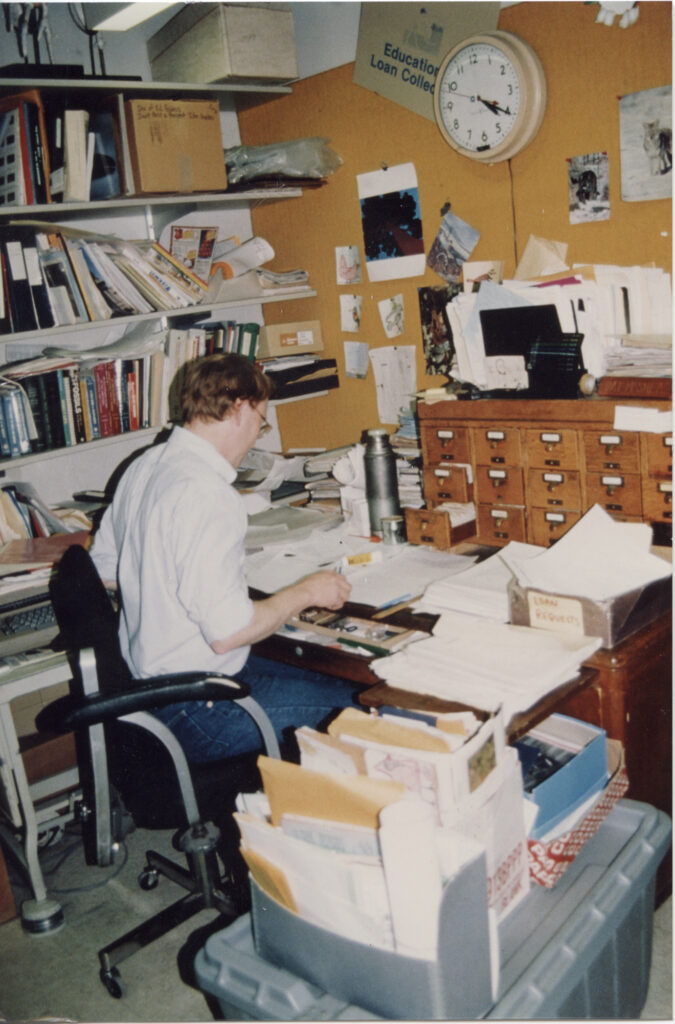

The inclusion of the Carnegie Museum field crew in the dedication is particularly apt because Guilday never visited Cumberland Bone Cave or many other sites he studied. His life and career, which included serving in a battle-tested US Army infantry unit during World War II, were immeasurably altered in 1952 when at the age of twenty-seven he contracted polio. The virus tremendously reduced his strength, necessitating the periodic use of an iron lung in his home for the rest of his life. Guilday’s visits to the halls and offices of his established workplace were rare during the next three decades, but with the ceaseless assistance of his wife Alice, the creation of a functional paleo lab in the basement of the couple’s home, and the physical and intellectual contributions of a tireless field crew, he earned a reputation as one of the research strengths of Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

In making a thorough case for the importance of Cumberland Bone Cave to our understanding of past mid-Appalachian environments, the new publication also realistically presents much of the paleontological work at the site as a salvage operation. Little is known with certainty about how the cave, a multi-chambered cavity within a limestone ridge a few miles northwest of Cumberland, was discovered or explored. The story of its recognition as a fossil site is, however, well documented. Beginning in 1910, the Western Maryland Railroad cut a passage for a new line of tracks through the cave-bearing limestone ridge, destroying a significant portion of the subterranean feature. In 1912, when fossilized bone found among excavated rubble was presented to a paleontologist in Washington, D.C. at what is now the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, professional fossil collecting efforts were quickly organized.

A well-illustrated 15-page chapter chronologically profiles the subsequent paleontological investigations of still intact cave chambers, including the intermittent work by a Carnegie Museum of Natural History team between 1964 and 2006. The summary hints at the physical challenges of work in the cave’s tight quarters, notes the cooperation of the railroad company on several occasions when heavy equipment was required for excavation, and emphasizes the current importance of determining exactly where, within this railroad bisected site, particular crews collected fossils. This tally of organized human efforts, along with later chapters listings the fossils collected from the site, raises the very same question that puzzled dozens of investigating paleontologists: How did the remains of such a varied set of ancient creatures come to be deposited in Cumberland Bone Cave?

The author team presents three scenarios. 1) For creatures such as bats, bears, wolves, and peccaries, who used portions of the cave for dens or hibernation chambers, a natural death within their shelter could have eventually led to fossilization. 2) Vertical fissures connecting cave chambers to the ground surface above them functioned as pit traps, occasionally capturing creatures unlikely to otherwise visit the cave. 3) In actions ranging from roosting owls coughing-up pellets of vole bones to wolves bringing larger prey to waiting pups, predators who relied upon the cave for shelter repeatedly brought prey remains into the system. A fourth scenario, involving bones washed into the cave, was rejected because recovered fossils lack evidence of water wear and sand and gravel are absent in cave matrix.

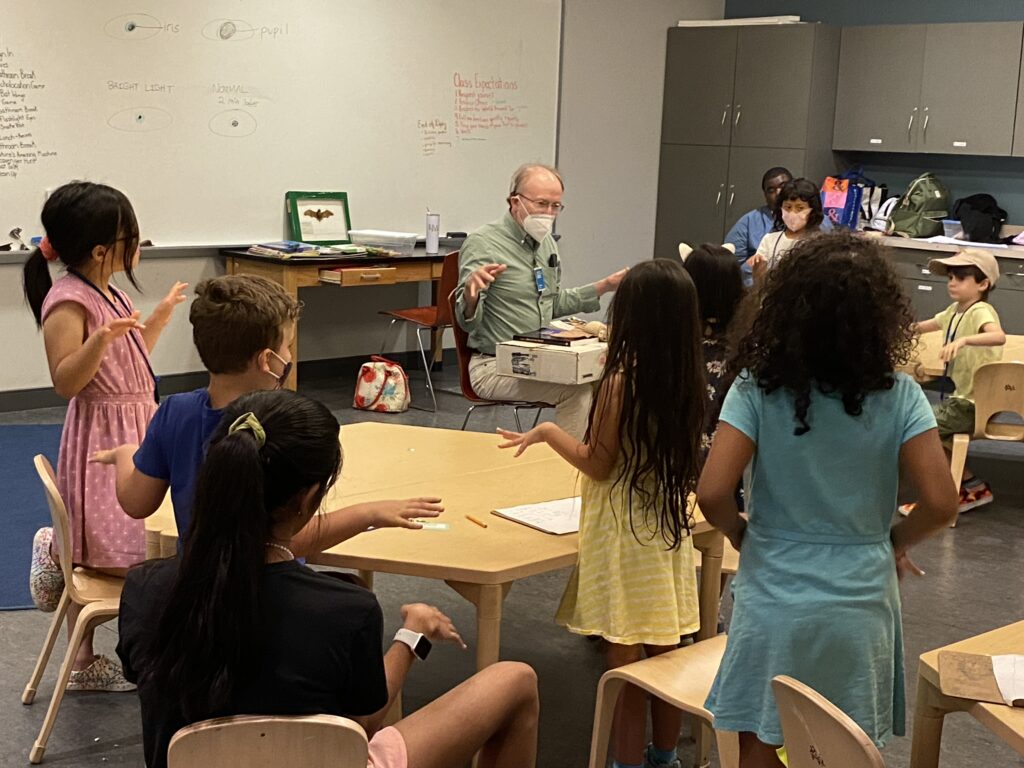

The publication’s clarity in explaining ancient deposition and other complex puzzles related to Cumberland Bone Cave will hopefully serve an audience outside Pleistocene Paleontology. The physical labor, disciplined thought, and wide sharing of information outlined in the narrative and referenced in a 23-page biography, make the work a landmark example for any teacher or student interested in the methods of science. Fortunately, the publication is widely available. Copies can be electronically downloaded for free from Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press.

Cumberland Bone Cave is no longer an active research site, but the fenced entrance of its main entrance draws the attention of bicyclists passing near the four-mile mark of the 150-mile Great Allegheny Passage trail.

Pat McShea is Educator Emeritus at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

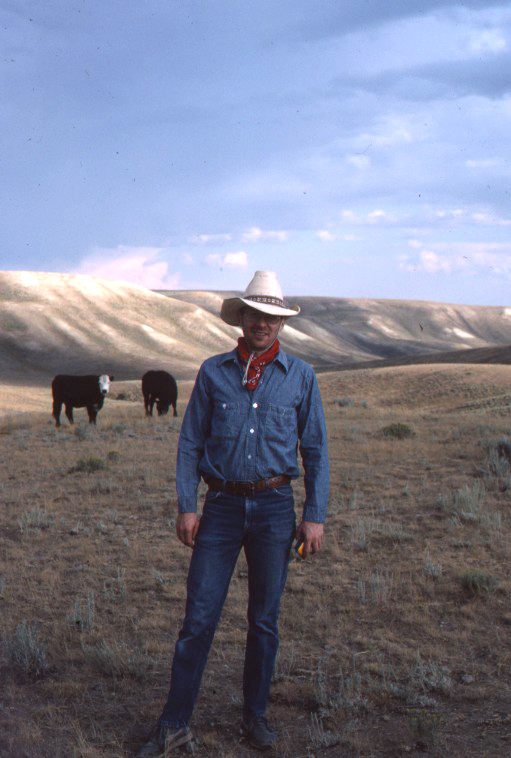

Hunting for Fossil Frogs in Wyoming

Type Specimens: What are they and why are they important?

Uprooted: Inside the Museum’s New Exhibition on Invasive Plants

![IMG_6141[7853566] museum label comparing grains of rice to seeds](https://carnegiemnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/IMG_61417853566-932x1024.jpg)

![PXL_20250413_183012905[10352] Uprooted label on diorama glass](https://carnegiemnh.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/PXL_20250413_18301290510352-1024x769.jpg)