by Jonathan Rice

Spotted lanternflies are a “true bug,” cousins of the cicada and stink bug. Unlike our native bug species, these invasive bugs feed on a very wide variety of plants and don’t have enough native predators or parasites to keep their population in check. Their favorite food is tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), which is already widespread in our area. This means their population is exploding, and Pittsburghers are looking for ways to get rid of them.

There’s no special pesticide that targets the lanternflies. However, we can outsmart them.

Spotted lanternflies display a unique behavior of climbing up tree trunks (or any other vertical surface), falling to the ground, and climbing up again. This is repeated many times throughout each stage of their life cycle. By using this behavior to our advantage, we can trap spotted lanternflies. The best currently used traps include circle traps and oviposition traps, which corral the lanternflies so they can be contained and destroyed. You can make circle traps as a DIY project, or you can order them premade.

Sticky traps: to stick or not to stick?

Although sticky traps (tape, sticky sheets, and glue traps) have been suggested in the past for spotted lanternfly control and are currently used by some landowners, these are extremely dangerous for birds. Sticky traps can kill many species of local birds that forage on tree trunks, including woodpeckers, nuthatches, and wrens. After the birds are stuck to the trap it becomes impossible for them to free themselves and they will die a slow and miserable death.

If you find a live bird or mammal stuck to a lanternfly sticky trap, do not try to remove the bird yourself. Cover any remaining sticky areas on the trap with plastic wrap to reduce double sticking the bird (or yourself), remove the entire trap from the tree, and take it to the nearest wildlife rehabilitation center. If you must use a sticky trap, ensure it is covered with a wire mesh (hardware cloth or similar) to prevent anything larger than a lanternfly from touching it. Check sticky traps at least once a day to ensure no birds or mammals have been caught.

Jonathan Rice is Urban Bird Conservation Coordinator at Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s environmental research center.

Related Stories

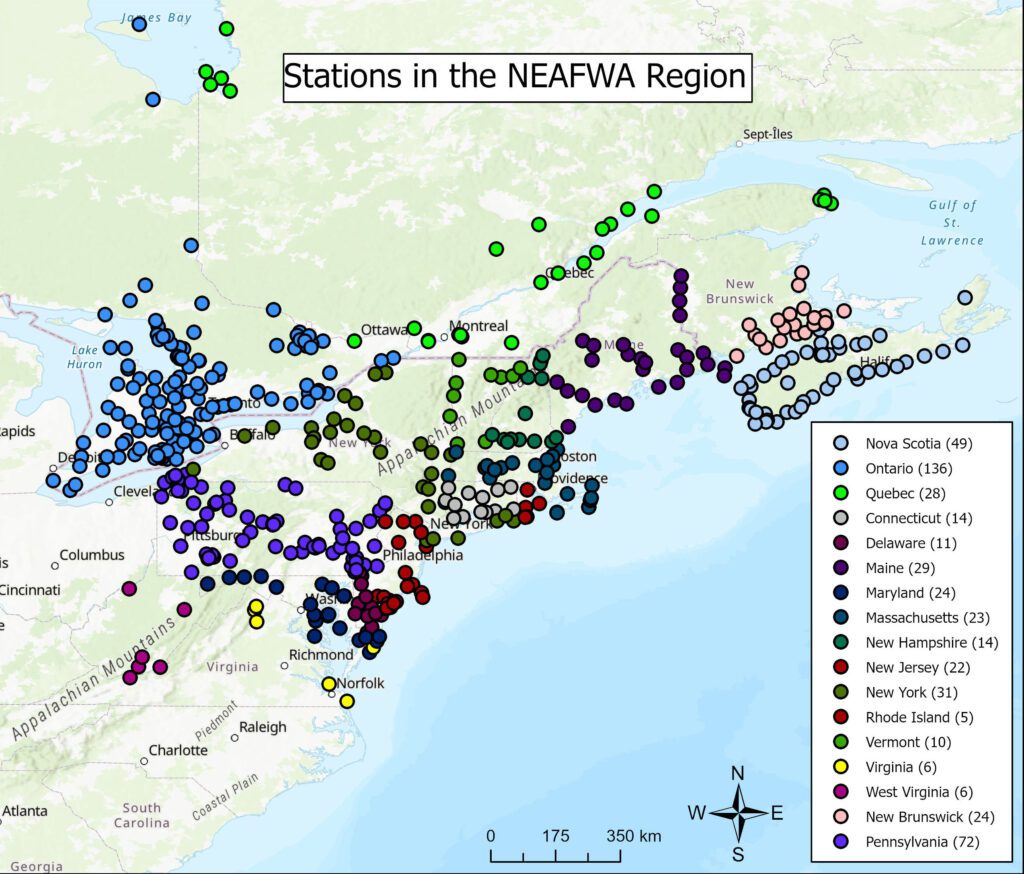

Tracking Migratory Flight in the Northeast

A Summer Internship at Powdermill

Can’t Choose Just One: Asking an Entomologist to Name Their Favorite Native Species

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Rice, JonathanPublication date: September 6, 2023