by Mason Heberling

Corn is a staple crop known well by many across the world. Corn is used in a variety of ways including human food (from corn on the cob to corn syrup), animal feed, ethanol production, and especially this time of year, fall decoration and corn mazes. Corn is an economically important crop worldwide, with over 81 acres expected to have been harvested in the US alone this year. But where did this plant come from?

Corn, better known to many as maize (Zea mays), is a domesticated plant. Yes, plants can be domesticated, just as your pets. Corn was domesticated from a wild grass species known as teosinte in Mexico approximately 8,700 years ago. Like many other food crops, corn was domesticated by humans through artificial selection – that is, through selective breeding for traits of interest over many generations, causing the evolution of a species. In the case of corn, teosinte evolved through human intervention by selecting seed from plants with desirable traits (such as large cobs), planting those seeds, again selecting the “best” plants, and repeating over decades. Eventually, teosinte evolved from a many branching grass with small seed cobs to what we recognize as corn today – tall, unbranched plants with large, tasty cobs.

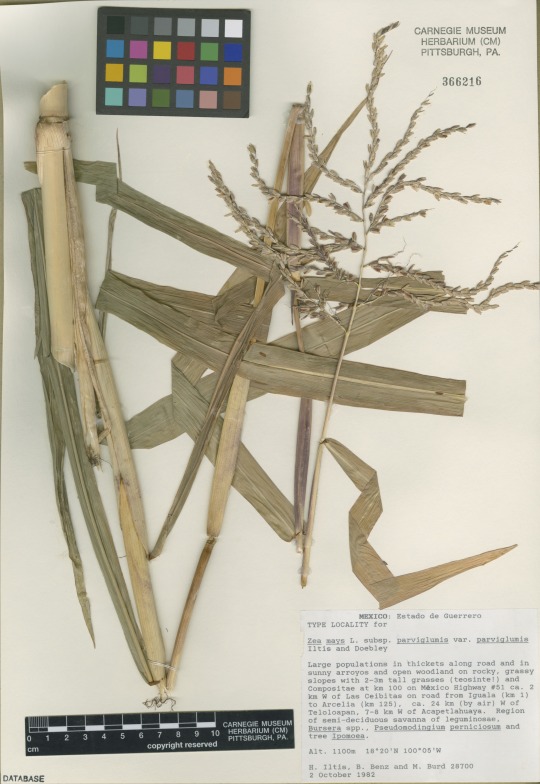

This specimen is of a species of teosinte (Zea mays subspecies parviglumis) that is thought to be the close relative of the domesticated crop we know today (Zea mays subspecies mays). This specimen was collected near the site of domestication in Mexico on October 2, 1982 by Hugh Iltis, a botanist and geneticist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studied teosinte species, and an influential conservationist. Note the species name on the label “Zea mays L. subsp. parviglumis var. parviglumis Iltis and Doebley” – his name at the end denotes Iltis was one of the scientists who named the taxonomic variety new to science in 1980. It was also collected in the “type locality,” meaning from the same spot where the specimen used to describe the species was collected.

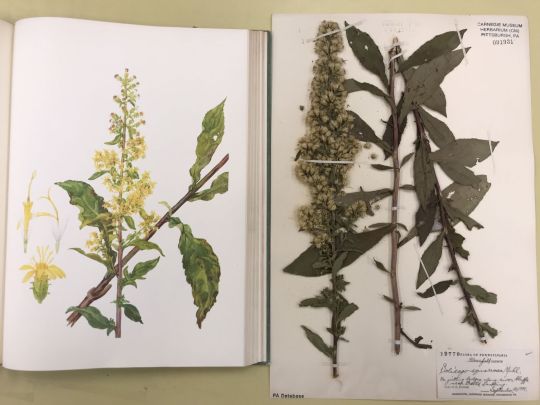

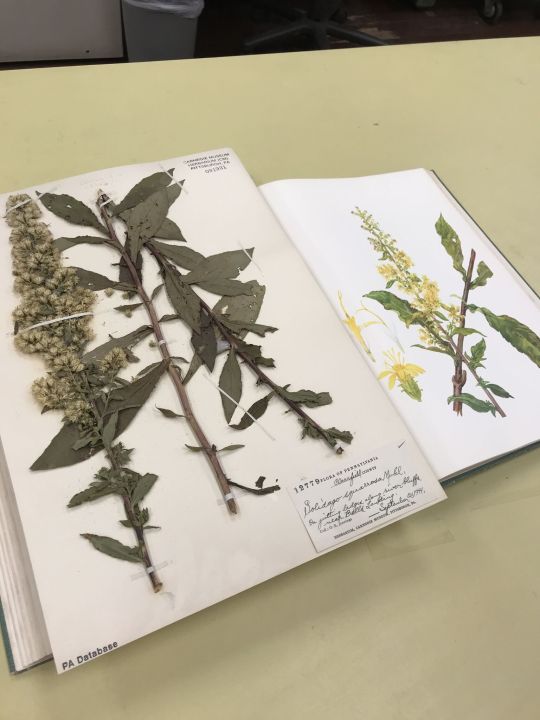

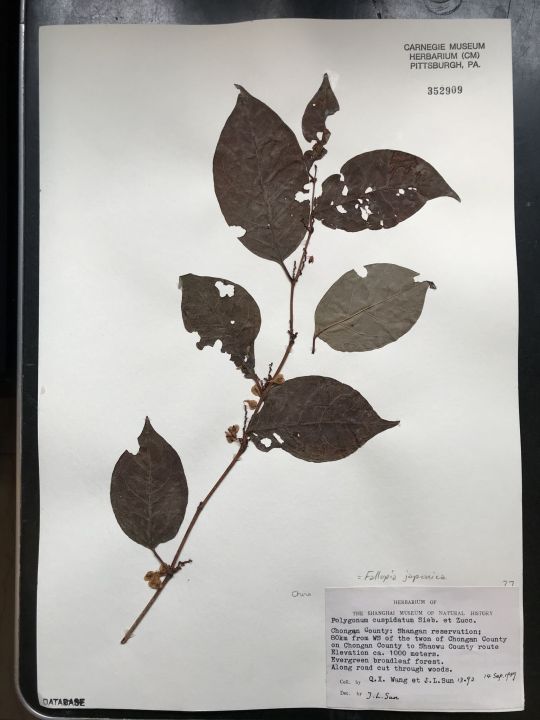

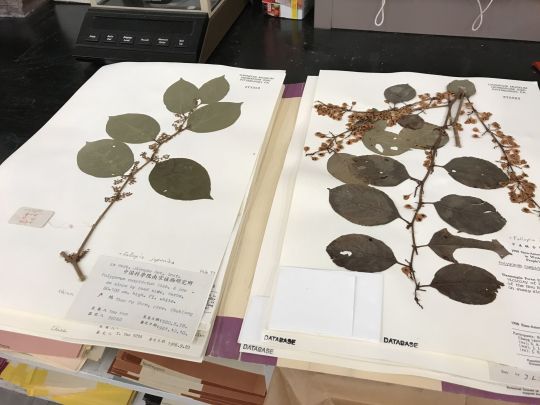

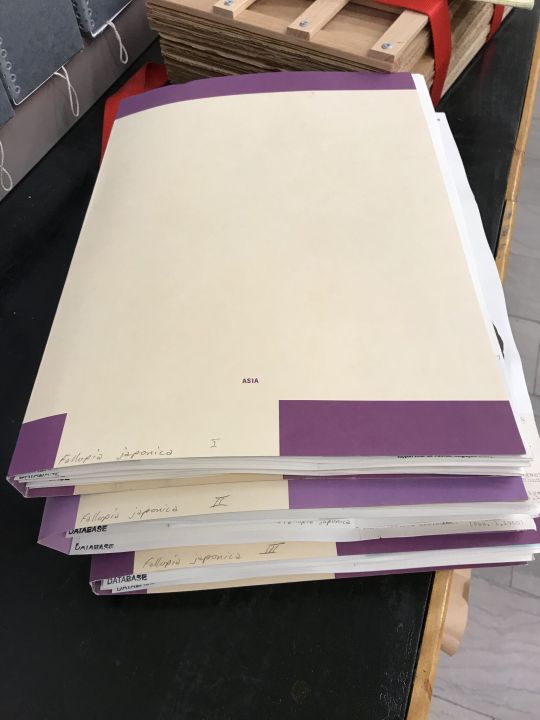

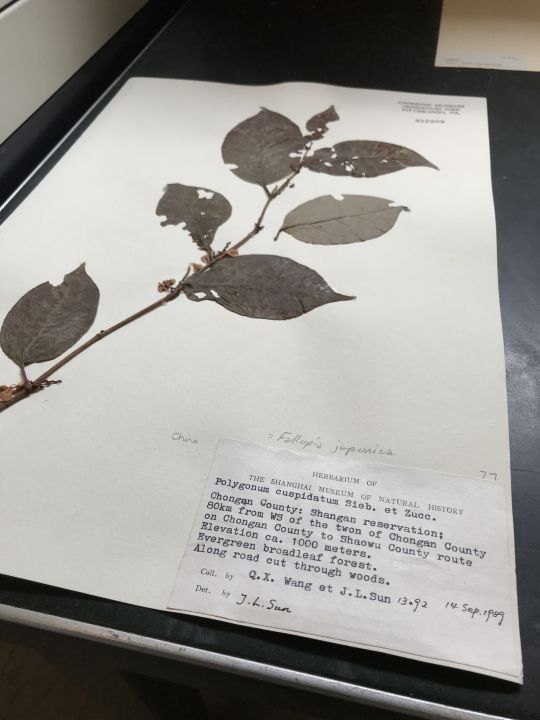

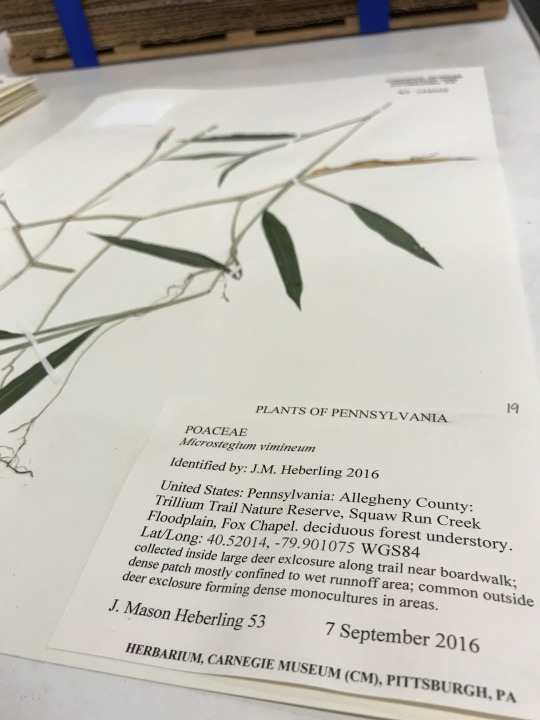

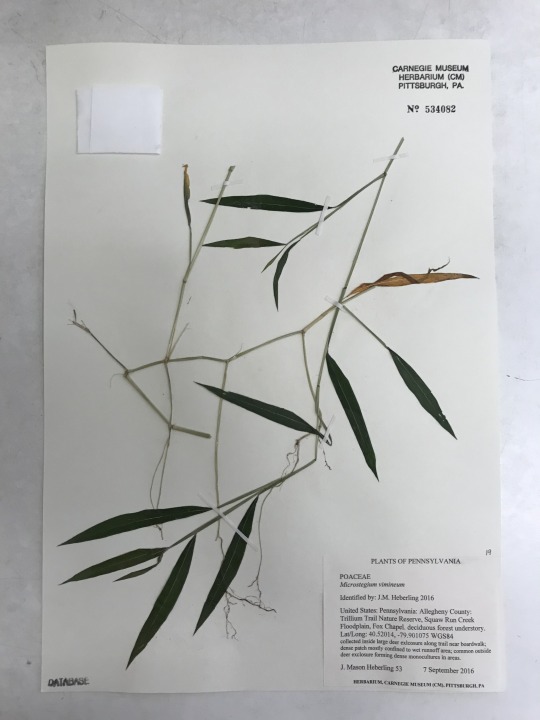

Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They have embarked on a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.