by John Wible

World Pangolin Day 2024 is on February 17, a day to raise awareness of pangolins or scaly anteaters, one of the most unique and endangered mammals on Earth. Their scales are harvested for traditional medicines that see them as cure-alls, but their scales are made of keratin like your fingernails and hair. Their scales are as medicinally effective as biting your nails.

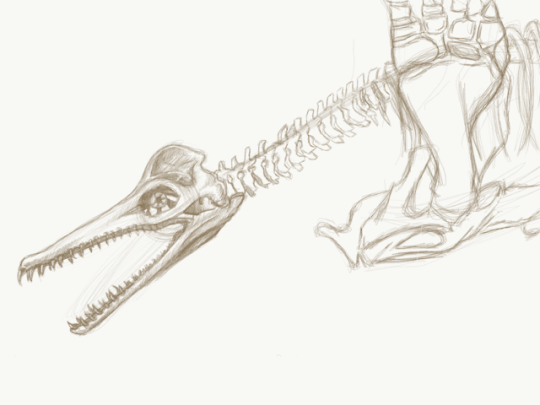

Although I will get to pangolins, I am starting with our feathered avian friends. Birds have a Y-shaped bone in their chest called a furcula (Latin for little fork). It is part of the flight apparatus and is thought to be formed by the fusion of the right and left clavicles (our collarbones). However, some researchers think it might be a different bone called the interclavicle, which in mammals is only found in monotremes, the egg-laying mammals. Some non-avian dinosaurs have a furcula, which is part of the evidence placing them on the bird family tree. The furcula is commonly called the wishbone because of the practice of making a wish on the bone! You grab one arm and someone else grabs the other; both make wishes and then pull; whoever gets the larger piece will have their wish come true.

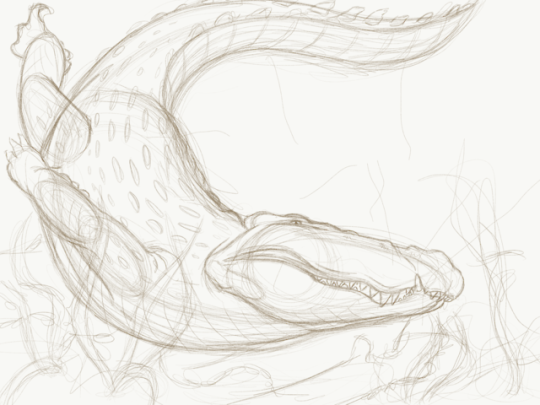

In celebration of World Pangolin Day, I want to introduce you to a mammal “wishbone.” If you search through the mammalian literature, you will not encounter a bone identified as a wishbone. Nevertheless, a small, select group of mammals have a pair of bones that looks, to me anyway, like a furcula. Here is an example.

The lower jaw, the mandible, is made up of right and left bones called dentaries. They meet on the midline at the chin. In humans, the right and left bones are filled with teeth, fused on the midline, and don’t look like a furcula! The northern tamandua from Central America differs in that there are no teeth, the right and left bones are held together only by soft tissues, and it looks like a furcula! How does the tamandua survive without teeth? Tamanduas are social insect feeders (ants and termites) that swallow their prey whole; tamandua parents don’t have to worry about their kids chewing with their mouths open. Now, although the tamandua lower jaw looks kind of like a wishbone, when pulled apart there won’t be a winner as the split will be down the middle with the two halves the same size.

The vast majority of the 6,500 species of living mammals have teeth; some have dentaries fused like humans and some have them unfused like the tamandua. Of the 6,500 species, there are 31 that are toothless as their normal condition. These 31 fall into two camps: 15 are baleen whales, including the Earth’s largest animal, the blue whale, which are filter feeders; and 16 are social insect feeders like the tamandua. However, all 31 have a mandible that is reminiscent of an avian wishbone. The 16 social insect feeders are from three unrelated lineages that have convergently adapted to eating ants and termites. The three lineages are:

- Spiny anteaters or echidnas (monotremes) found in Australia and New Guinea (four species).

- True anteaters (myrmecophagids) found in South and Central America (four species including two kinds of tamandua).

- Pangolins (pholidotans) found in Africa and Asia (eight species).

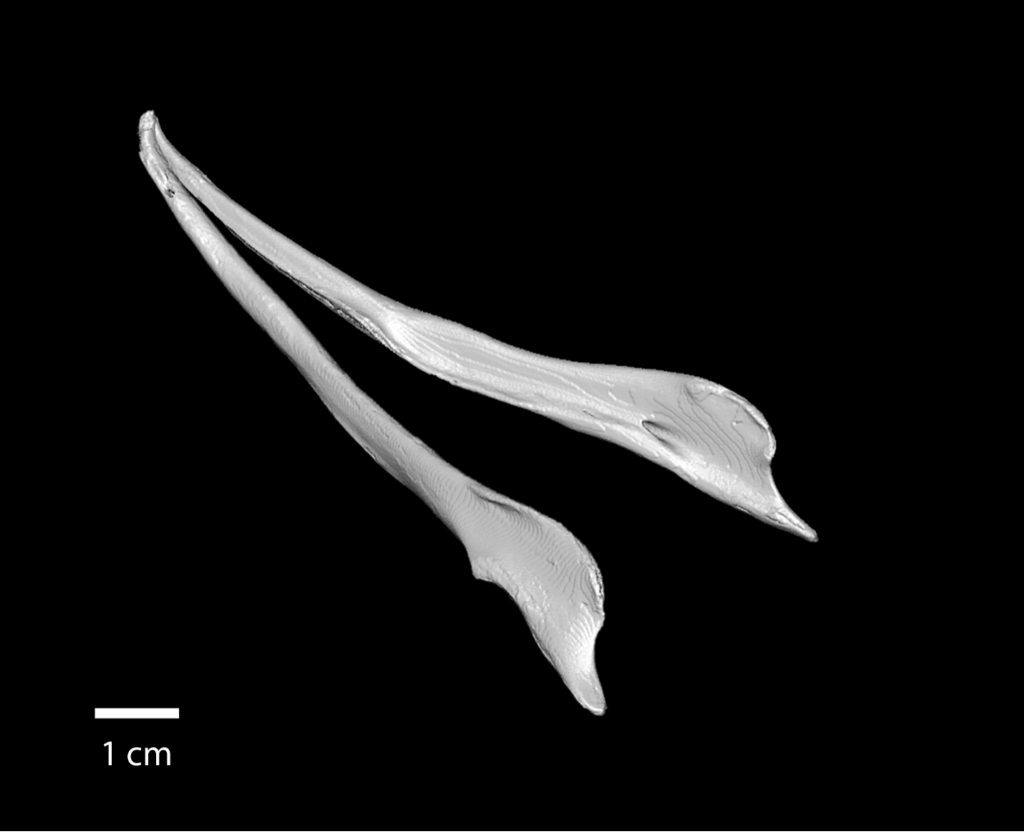

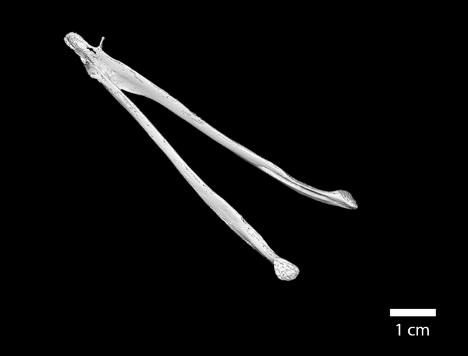

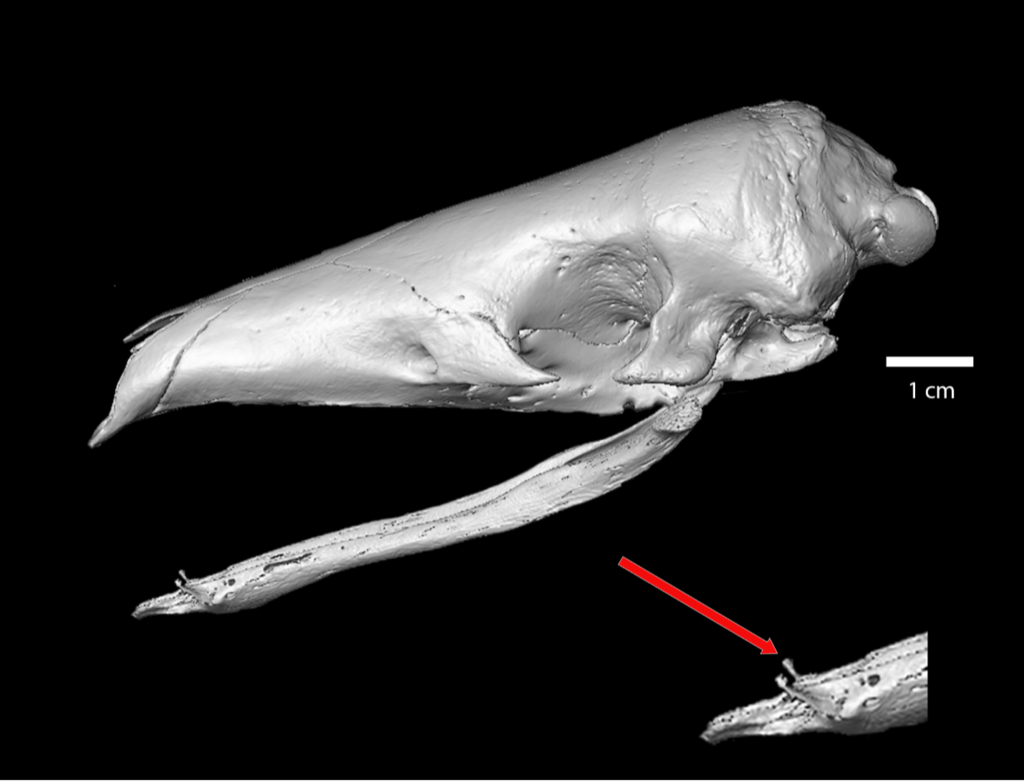

The mandibles of the #1 and #2 look like that of the northern tamandua. The left and right sides are not fused and the mandible is skinny in the front and larger in the back where it articulates with the skull. #3, the pangolins, are really different. The left and right sides are fused at the midline and the mandible is larger at the front.

The other very odd thing about the pangolin mandible is that it has a pair of bony prongs at the front that look somewhat like teeth (red arrow). Doran and Allbrook (1973: Journal of Mammalogy) dissected the pangolin tongue and reported that the lower lip was attached to these prongs, but they did not illustrate this or explain it further. Pangolins are clearly doing something different with their mandible than the tamanduas and echindas are, but what, I don’t know. Whatever it is, it has been around in pangolins for at least 35 million years! There was a pangolin that lived in the American West during the late Eocene named Patriomanis americana and it has a set of mandibular prongs just like those in the Sunda pangolin shown here. The other difference with the pangolin mandible is that when subjected to a wishbone pull, it might not break down the middle and be more like a furcula.

I have left the baleen whales until the end. Are their mandibles more like the tamandua, the pangolin, or neither?

Baleen whales are more like the tamandua with the right and left sides unfused and the mandible larger in the back than the front. If you were able to do the wishbone pull on the blue whale, there would be no winner and someone would likely lose by throwing their back out!

John Wible is Curator of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

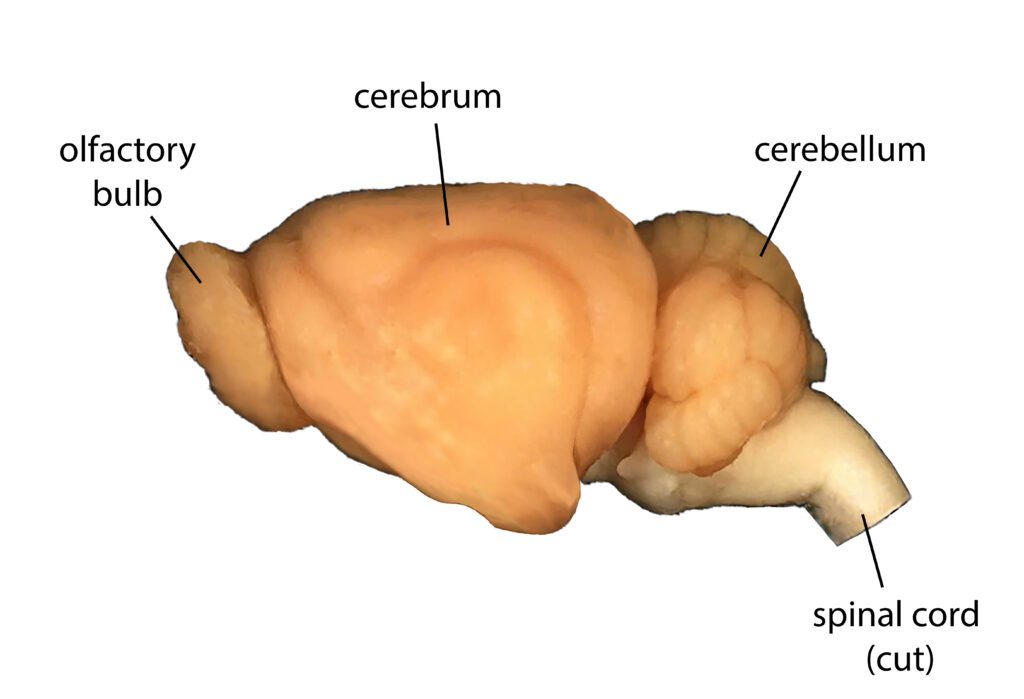

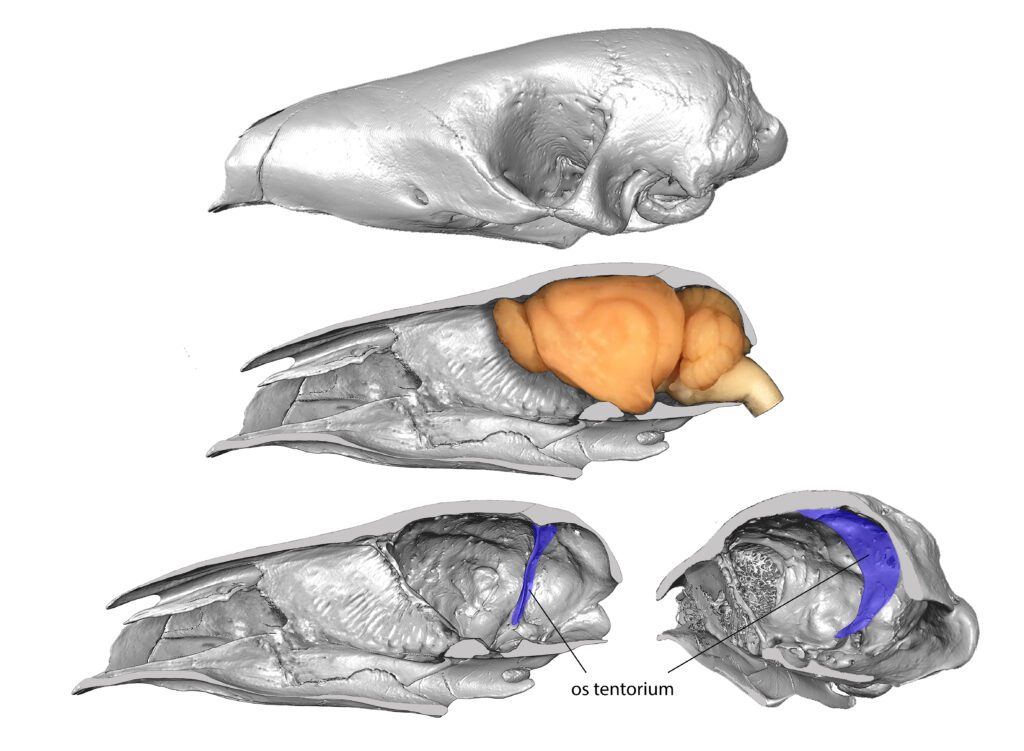

World Pangolin Day 2023 – The Mysterious Brain Bone

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wible, JohnPublication date: February 16, 2024