The order Coleoptera (beetles) is by far the most diverse of all living organisms. More than 350,000 species of beetles are grouped into more than 150 families.

In the above photo, you can see the many variations within one single family of beetles.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History

One of the Four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh

by wpengine

The order Coleoptera (beetles) is by far the most diverse of all living organisms. More than 350,000 species of beetles are grouped into more than 150 families.

In the above photo, you can see the many variations within one single family of beetles.

by wpengine

By Marc Wilson

Pictured above, the mineral hyalite is a type of non-precious opal that is usually formed in hot springs environments, like

Yellowstone National Park.

Hyalite often contains traces of uranium as impurities. When there is just the right amount of uranium in the hyalite, it causes it to fluoresce brilliant yellow-green under ultraviolet radiation, more commonly called “black light.”

Most fluorescent hyalite reacts best to the shorter wavelengths of ultraviolet but this specimen has an intense reaction to long wave ultraviolet. This is good for us because short wave ultraviolet is completely filtered out by glass or plastic, but long wave can penetrate through both allowing us to cause it to fluoresce with a UV laser pointer.

This remarkably fluorescent hyalite opal was discovered in Zacatecas, Mexico in 2013. It came from a very small deposit that is now completely worked out. We are very fortunate to have such stunning examples

from this unusual occurrence.

Marc Wilson is the head of the Minerals Section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

by wpengine

By Steve Rogers

The National Taxidermists Association met at Seven Springs in early June 2016 and Carnegie Museum of Natural History Collection Manager Stephen Rogers was invited to give a seminar on the early history of taxidermy in the United States.

On a whim he decided to create a piece for the competition held at this meeting. Since he is an historical taxidermy buff and collects old publications, tools, as well as antique furniture, he created a taxidermists’ work table as it may have been circa 1898.

The table held a skinned out flicker made to look fresh (coated with glycerin), a faux carcass and bits of flesh made of wax, a hand-wrapped artificial body which would have been put inside the skin, a book on the Birds of Pennsylvania opened to a hand-colored plate on flickers, and then eyes and tools that might be used in the process.

Behind the table was a re-created room with antique looking wallpaper with various decorations on the wall, deer antlers, an 1898 poster of a Winchester calendar, and a framed 1873 newspaper with a woodcut depicting a taxidermist and an ornithologist.

Assorted other birds, a tool chest with period tools, and supplies to mount birds (excelsior, tow, cotton, glass eyes of different sorts, etc.) were also present. A library of 15 taxidermist and naturalist books published between 1874 and 1898 were in a lawyer’s glass-front bookshelf alongside a Stereoviewer with a handful of stereophotographs depicting taxidermy.

Glass jars containing what appeared to various noxious chemicals were set on top of the bookshelf. A number of people asked about the green chemical in one jar. Was it arsenic? – No, just some powdered lime Jell-O.

The public as well as the taxidermists who attended the convention were able to vote for pieces in the competition. The exhibit won ‘People Choice – Original Art’. But more importantly, it gave people and appreciation for history and reference for those that came before.

Steve Rogers is a collections manager at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

by wpengine

The image on this coffin canopy in Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt represents the ba, which was the spirit-like quality Egyptians believed all people possessed.

The ba is most often depicted as a human-headed bird. A person’s ba was considered important in the afterlife, where it could visit the world of the living during the day and return to the world of the deceased at night.

by wpengine

by Patrick McShea

Museum visitors sometimes offer spontaneous testimony to the deceptive power of taxidermy.

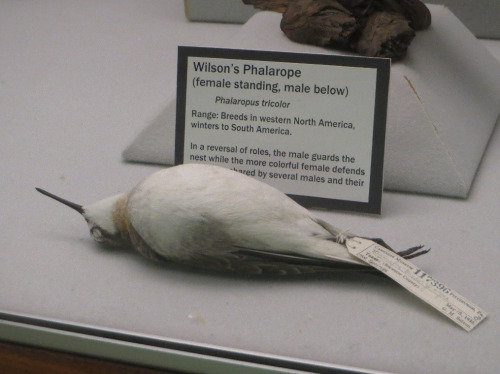

“There’s a dead bird!” is a comment frequently voiced by people encountering a bird specimen lying on its back in Bird Hall, such as the Wilson’s phalarope pictured below. These specimens, so often called “dead birds”, are actually called study skins.

Study skins are a traditional form of specimen preparation for birds in scientific collections. Unlike taxidermy mounts, which attain a pretense of life through concealed body forms, strategically positioned wires,

and glass eyes of the appropriate size and color, the cotton-stuffed study skins appear lifeless.

The more than 154,000 bird study skins in the museum’s research collection have all undergone similar preparation. For each specimen the full skin of the bird was carefully removed from the underlying muscle,

skeleton core, and internal organs, preserving every feather of the creature. Such Uniform preparation creates a standard for comparisons of features between both similar and strikingly different specimens. In addition, the low profile of study skins allows for their storage in shallow cabinet drawers in the manner of the passenger pigeon study skins pictured below.

Although taxidermy mounts far outnumber study skins in Bird Hall display cases, the “skins” play an important role by representing the most numerous form of preserved specimens in the museum’s vast bird collection. Whether or not adjacent taxidermy mounts seem more alive because they share display space with the skins is something you may judge for yourself during your next museum visit.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences of working at the museum.

by wpengine

This decorated ware jar in Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt is dated between 3650 and 3300 B.C. The pierced lugs on each side of the jar were used to suspend it, possibly from a tripod.