In the fall of 2018, Albert D. Kollar and John A. Harper (volunteer and research associate) of the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology in collaboration with the Pittsburgh Geological Society conducted a geology field trip titled: Geology of the Early Iron Industry in Fayette County, Pennsylvania. Back then, we had no idea this field guide would be recognized by the Geoscience Information Society with their GSIS Award 2019 for Best Guidebook (professional) at the Annual Meeting of the Geological Society of America (GSA). On September 23, 2019, Albert attended the Awards Luncheon in Phoenix, Arizona, to receive the GSIS Award.

As stated by the GSIS committee chair, “The Geology of the Early Iron Industry in Fayette County, Pennsylvania is well-written and well-illustrated, with both professional and popular sections. I can see local geology teachers taking students on these trips to show a chapter in the development of an important early ore industry in the United States. With the aid of detailed road logs guidebook users can see and learn about the geology, industrial development, history, and fossils in Fayette County. Field Trip leaders can use the guidebook to expand on several topics, depending on the interests of their trip attendees. An additional benefit of the guidebook is its free availability online, so any traveler with an interest in the area can explore on their own. The Pittsburgh Geological Society has performed a great model for other local societies that are interested in spreading the benefits of their field trips to wider audiences.”

In receiving the award, Kollar opined that the guidebook has been recognized for the diverse geology of the region and the many historical sites that can be seen and visited respectively throughout southwestern Pennsylvania. These include, the geology of Chestnut Ridge, a Mississippian-age limestone quarry with abundant fossils and Laurel Caverns, the history of oil and gas exploration, the historic Wharton Charcoal Blast Furnace, the geology of natural gas storage, the country’s First Puddling Iron Furnace, and the birth place of both coke magnate Henry Clay Frick and Old Overholt Straight Rye Whiskey, West Overton, Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

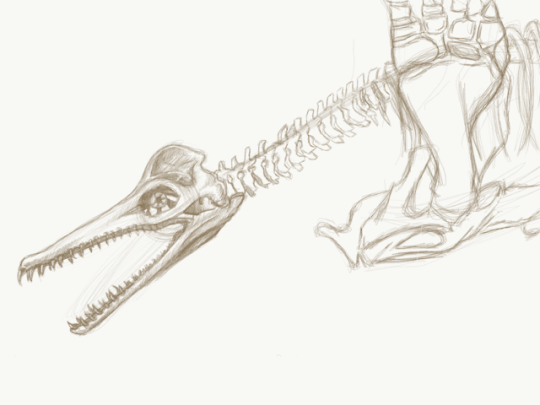

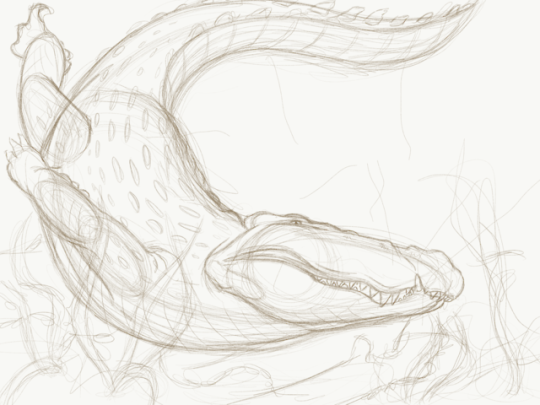

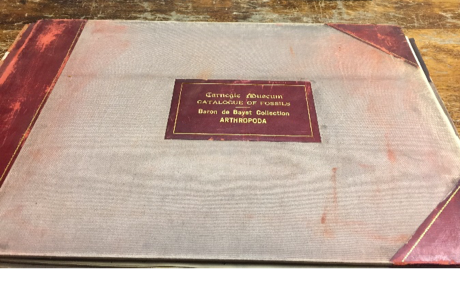

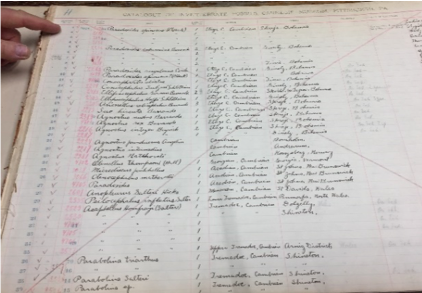

Another feature of the guidebook is its dedication to Dr. Norman L. Samways, retired metallurgist, geology enthusiast, and good friend who spent many years as a volunteer with the Invertebrate Paleontology Section of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Sam, as we called him, passed away in February 2018. His contribution came about when he was instrumental in the research and writing of the Geology and History of Ironmaking in Western Pennsylvania, with his co-authors John A. Harper, Albert D. Kollar, and David J. Vater, published as PAlS Publication 16, 2014. Moreover, Sam was solely responsible for a new historical marker, AMERICA’S FIRST PUDDLING FURANCE along PA 51, dedicated on September 10, 2017 by the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission and the Fayette County Historical Society. David Vater contributed to the guidebook’s content by drawing a schematic diagram of a typical puddling iron furnace, which is greatly appreciated. Key fossils and iron ores of the section’s collection are referenced as well. The cataloged fossils cited in peer review journals authored by section staff and research associates includes those on the trilobites by Brezinski (1984, 2008, and 2009), Bensen (1934) and Carter, Kollar and Brezinski (2008) for brachiopods, and Rollins and Brezinski (1988) for crinoid-platyceratid (snail) co-evolution.

In recent years, the section has run highly successful regional field trips about various geology and paleontology topics based on the museum collections, collaborations with the Pittsburgh Geology Society, the Geological Society of America, Osher Institute of the University of Pittsburgh, Nine-Mile Run Watershed, Allegheny County Parks, Pittsburgh Parks Conservancy, Montour Trail, Carnegie Discovers, and the section’s own PAlS geology and fossil program. A future field trip is being planned to assess the dimension stones that built the Carnegie Museum and noted architectural building stones of Oakland.

Albert D. Kollar is the Collection Manager in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.