Are you fascinated by plants? Fascination of Plants Day is upon us (don’t worry, we didn’t know it was a thing either, but agree celebration is in order!). As you might guess, we in the Section of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History are definitely into any and all things plants. Plants are inextricable from our daily lives and play critical roles in our environment. Plus, they are just pretty cool, too. Amid chirping birds or a lion chasing a gazelle, they might be easy to overlook, but they are well worth your attention. From the sidewalk cracks in front of the museum to a remote tropical rainforest, there is a lot to celebrate.

With over half a million plant specimens in the Carnegie Museum herbarium, we have a lot to be fascinated by. Botanists here at the museum and across the world are making new discoveries about plants through these collections. On this 5th annual Fascination of Plants Day, I’d like to share some exciting new work in our collection – extracting fungal DNA from herbarium specimen roots collected over a hundred years ago.

Unexpected inspiration often comes from looking at old specimens in new ways. Museum specimens were collected for many different reasons. The uses of specimens are many, and recently, being used in new ways. Museum specimens have a lot to tell us. If we look.

Recently, I became fascinated by something often ignored – roots on herbarium specimens. Why do herbarium specimens have roots?

It is standard practice for botanists to collect the entire plant when possible. Of course, that isn’t possible for a huge tree, but many plants can fit nicely on an herbarium sheet, roots and all. And not only do many specimens have roots, but they have soil too.

For some plants, roots can be very helpful for identification. But for the most part, roots on herbarium specimens have not been generally used. But what can 100-year-old roots tell us?

With this new fascination with herbarium specimen roots, I contacted Dr. David Burke, a microbial ecologist and expert in belowground forest ecology at the Holden Arboretum in Kirkland, Ohio. David studies belowground microbial soil communities and their interactions with plant roots. Nearly 75% of all flowering plant species form close relationships with mycorrhizal fungi. Many plant species in our forests across the eastern United States rely upon these mycorrhizal fungi to obtain water and nutrients necessary for growth. In return, the fungi get food (sugars) from the plant.

Can herbarium specimen roots tell us about relationships between mycorrhizal fungi and plants? And perhaps more importantly: Have human activities affected these plant-fungal relationships over the past century?

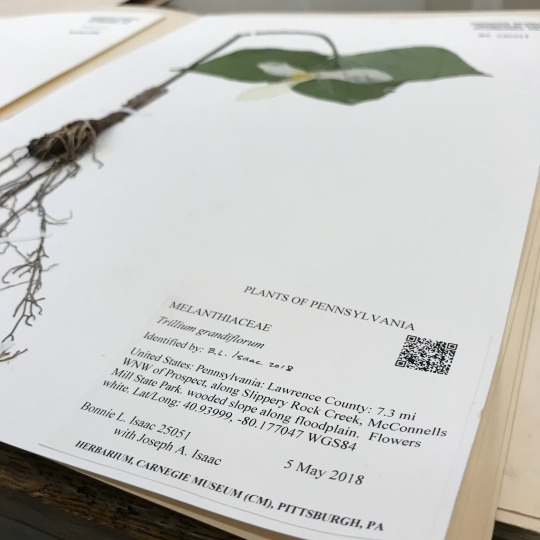

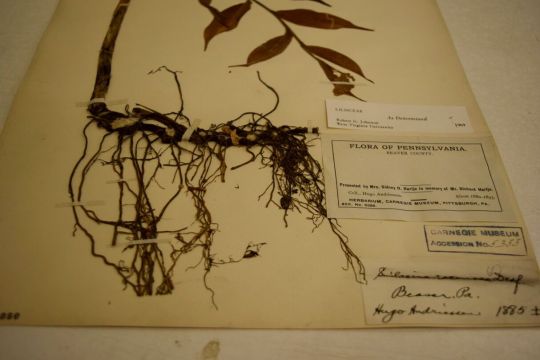

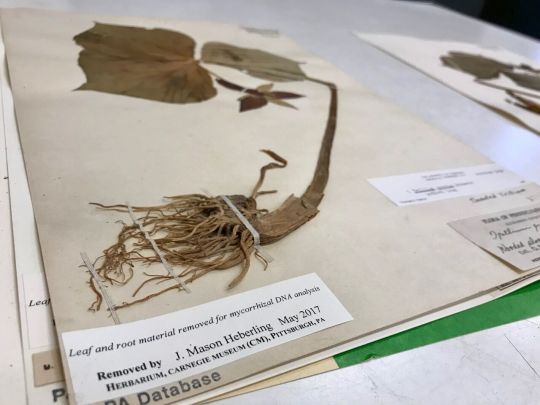

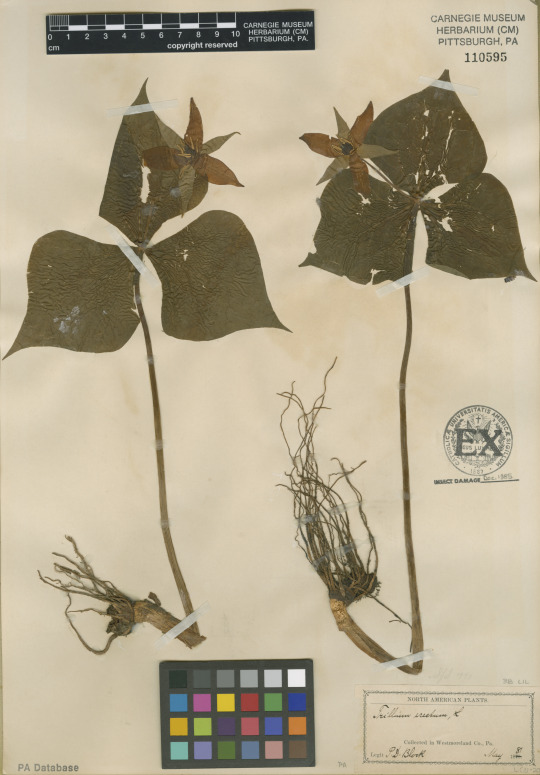

David Burke had not extracted fungal DNA from herbarium specimen roots, but he was eager to try. (In fact, to our knowledge, no one had done this with herbarium specimen roots before.) We sampled roots from herbarium specimens of four common forest wildflowers collected in western Pennsylvania between 1881 to 2008. These species included some favorites familiar in our area: red trillium, large-flowered trillium, false Solomon’s seal, and jack-in-the-pulpit.

David was able to extract and sequence fungal DNA from plant roots as old as 137 years old! We published our results in a special issue on belowground botany in Applications in Plant Sciences. You can read the full study here. While there is still much to be done, we showed that museum collections across the world hold enormous potential to provide new insights in the basic belowground biology of plants. They can also help us understand how human activities may affect the web of life in overlooked ways.

Herbarium specimen roots have a lot to tell us about the past, present, and future of our forests in the Anthropocene. And that is fascinating!

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.