by Bob Androw

When visitors tour the insect collections in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology, the conversation often turns to numbers. How many rooms house the collection? Three, all quite full. How many total drawers are in those rooms? Well, roughly 30,000, at last count. How many specimens are in those drawers? We like to quote a figure of 13 million, give or take a few (but no one has counted recently). How many staff members are there to take care of all those bugs? Well – seven on a good day – that’s just 1,857,143 specimens per staff member…

And then the big questions always hit – why do you have so many specimens? Why do you have so many of the same species?

While there are many rarities represented by one to just a few specimens, the truth is that the majority of species are represented by several to many hundreds of individuals, referred to as a ‘series.’ So how do these series end up in the collection, and what is the purpose for multiple examples of individual species?

A simple answer, but not one that explains much, is that the age of the collection alone contributes to long series, especially of common species. Since its founding in 1896, if just a single red-spotted purple butterfly (Limenitis arthemis (Drury)), were deposited each year, 122 specimens would now be present. But the series of that common species probably numbers ten times that by now. So how, and why?

Over the years, museum staff have been active in traveling and collecting and were, and are, continually adding new materials to the collection. But an even greater number of specimens have come in the form of donations – entire collections, representing lifetimes of work, often come to us after their owner’s passing. These are sometimes from professional entomologists, but more often they are the legacy of non-professional, avocational collectors. These donated collections all vary drastically in their holdings, but common species are generally present, increasing the length of series of these taxa in the museum’s collection.

Back to all those red-spotted purples! Collected by a variety of people in a variety of places and times, they provide examples of the individual variation within the species, as well as critical locality and temporal documentation – or data – that help researchers understand the life history and distribution of the species. In these times of increasing global temperatures, the old data can be used as a baseline to compare against current information – does the butterfly still occur where it had in the past? Does it occur further north, now that the climes are more temperate in areas that used to be too cold? Or has it been pushed into higher elevations to evade hotter conditions in its historical habitat? By having large series, there is more data to help fill out the story of this butterfly species’ life history – past and present.

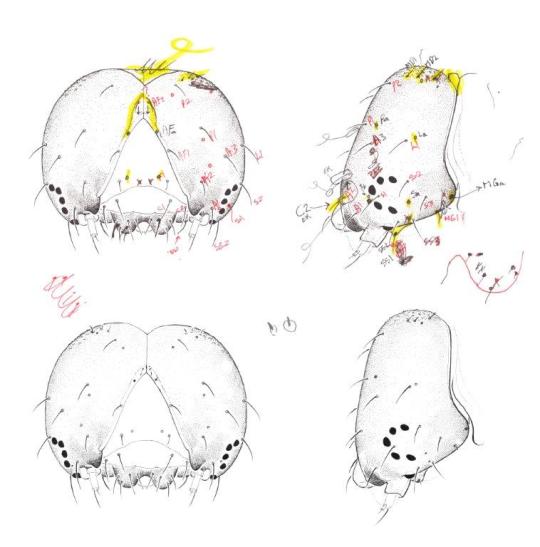

When those red-spotted purples were caught, the collectors were probably aware of what species they were – but what about species that cannot be easily identified in the field? The vast majority of insects are small to minute and cannot be identified until they are prepared and examined under a microscope. In the insect world, small size is coupled with enormous diversity. Entomologists regularly collect long series in the field to increase the odds of documenting more diversity – more specimens likely mean more species.

Not only is there a great diversity of species, but many insects exhibit variation within a species – in size, in color, and in differences between females and males. Populational differences are often evident within a species – sometimes to the extent that subspecies are described, discrete in their distribution and readily separated by physical characteristics. In the longhorned beetle Gaurotes cyanipennis (Say), individuals vary in color from blue to green to coppery to purple and all color forms can usually be found together in any given locality. But if you examine a long series of museum specimens you will notice the majority of specimens collected in the central third of Pennsylvania are all purple – rarely any other colors. The reason for this has not yet been determined, but by having long series of this common beetle, the trend can be seen, and questions can be asked.

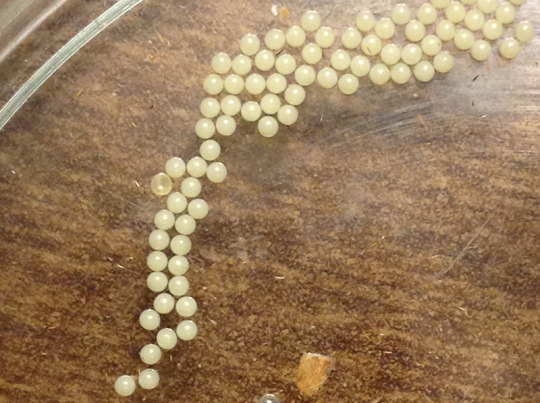

Insects can be collected by hand, one specimen at a time, but to more fully sample the biodiversity of a habitat, various types of traps can be deployed: pitfall traps; light traps; intercept and malaise traps; baited traps; with many specially designed to capture specific taxa. Traps allow for passive collecting over time, greatly increasing the volume, and diversity, of specimens compared to what a person could capture by hand. These trap samples can provide long series of specimens, insight into the biodiversity of a habitat and good data on population sizes. Select specimens are prepared, labeled and deposited in the collection and the remainder of the trap sample is archived to be available for future research. The specimens are not unlike the scores of books on a library’s shelves, their data labels all containing a little piece of the story about a living creature’s existence, documenting its occurrence in some place, at some time, on our planet.

So, when asked “why so many?”, the answer is multi-faceted: accumulation of specimens over time, from staff activity and donations of materials; the sheer biodiversity of insects composed of thousands of species; and long series documenting variation, distribution and seasonal occurrence. And chances are, as you read this, dozens more specimens are being added to the amazing insect collection at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Bob Androw is a Scientific Preparator in Invertebrate Zoology. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.