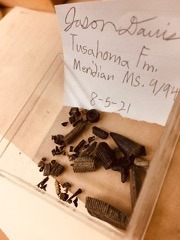

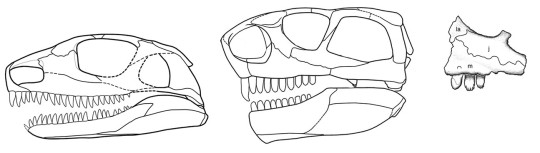

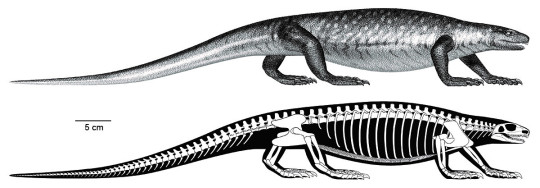

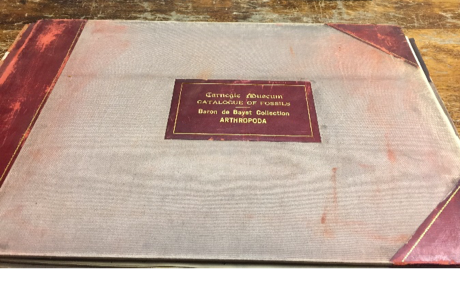

Teens (ages 13-18) are invited to Carnegie Museum of Natural History for a fun event celebrating the new exhibition, The Stories We Keep. Take the exhibit design challenge and learn what it takes to build engaging, exciting exhibitions. Check out the tools museum conservators use to preserve ancient objects, like a 4,000 year old wooden boat from Ancient Egypt. Discover the “Agents of Deterioration” that conservators dodge and deflect to keep artifacts safe, and see if you can guess the use of old-time objects. Stop by the lounge for a snack while you enjoy a night just for teens.

Whether you’ve already signed up for a free Teen Membership from Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, or just want to see what it’s all about – we hope you’ll stop by! Please register early to secure your free ticket; capacity is limited. Open to everyone ages 13-18.

Make your reservation today before this exciting event sells out. Free to everyone ages 13-18.

Teen Night: The Stories We Keep

Thursday, April 18, 2024, 5 p.m. to 8 p.m.

Community Access Membership is presented by

Teen Membership is generously supported by

The Grable Foundation and the Robert and Mary Weisbrod Foundation