At the Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh (JCC), the youngest students direct much of their own learning. “We focus on the philosophy of the of the Reggio Emilia Approach,” explains Emmanuelle Wambach, referencing the innovative childhood learning model named for the northern Italian town where it was developed more than 60 years ago. Emmanuelle, who has worked at the JCC since 2018, currently teaches a dozen pre-school students at the Squirrel Hill facility. Back in November, when this group of three- and four-year-olds became interested in birds and bird eggs, she was determined to assist their exploration of the topic.

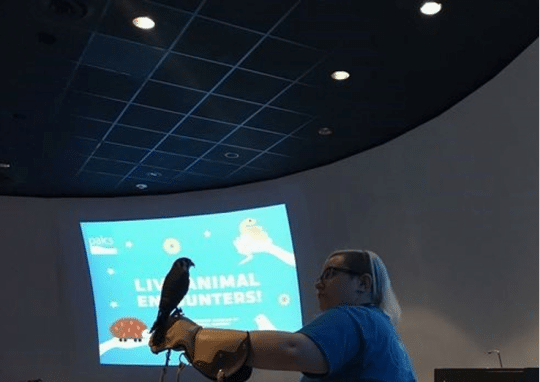

Through the museum’s Educator Loan Collection, she was able to borrow an encased taxidermy mount of an American Robin posed next to its nest and eggs, along with sturdy replicas of Bald Eagle, Golden Eagle, and Peregrine Falcon eggs. “There were some early discussions about the robin not being alive,” Emmanuelle recalls, “but we were able to make wonderful comparisons between the Peregrine Falcon and eagle eggs, and of course to the chicken eggs they were already familiar with.” The museum objects and the resulting discussions eventually led to group explorations of other resources such as the Audubon Society of Western Pennsylvania’s live camera feed documenting activity in and around the Bald Eagle nest in the Hays neighborhood of Pittsburgh.

This example of an educator connecting with a helpful resource was far from a direct link, however, and actually hinged on artistic accomplishment. Emmanuelle holds a Master of Fine Arts from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, and in sharing her talents with ceramics she has taught classes at several Pittsburgh area locations. She learned about the museum loan program when she was teaching ceramics at an afterschool program and met a fellow artist who had borrowed taxidermy mounts for students to use as drawing models.

When asked about the impacts of the ongoing pandemic on her teaching, Emmanuelle notes a reduced class size of 12 instead of 16, and praises her students’ ability to “wear their masks well.“ Then after some refection she describes a system of mutual support that naturally developed between the young learners and those leading them. “I’m certain they’re helping me get through this difficult time. You have no idea how good it is to have a four-year-old greet you by saying, ‘Miss Emmanuelle, I’m so glad you’re here today!’”

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.