Researchers from Carnegie Museum of Natural History have described impacts of climate change and land use on the size of organisms. Dr. Jennifer Sheridan, Assistant Curator of Amphibians and Reptiles, and Dr. Amanda Martin, post-doctoral researcher, review the causes that lead to changes in size as well as ecological interactions, while making the case for more research studying the combined effects of climate change and urbanization. The paper, entitled “Body size responses to the combined effects of climate and land use changes within an urban framework,” was published in in the journal Global Change Biology on June 27.

Body size is considered one of the most important traits of an organism, affecting thermal regulation, mobility, reproductive output, and capacity to acquire resources. Over many generations, body sizes usually increase within lineages. Recent observations, however, show a decrease in size over relatively short time periods. This could have profound ramifications for individual organisms and ecosystems alike. For example, size-related reproductive success means that interacting populations in the same location will be dominated by smaller species, leading to long-term changes in predator-prey dynamics. Most research suggests climate change as the primary driver of changes in size, but emerging research indicates that land use—especially urbanization—may also contribute.

Human-induced climate change has significantly altered temperatures since the 1950s, and temperature affects the size of organisms. At roughly the same time, the Earth has experienced rapid urbanization and a tripling of the human population. Unlike climate change, urbanization has been shown to cause an increase in size of some organisms due to the advantage size has on mobility, and the greater availability of food and other resources. Urbanization does not affect all organisms equally; however, and some species—including some birds—are unable to take advantage of food abundance in urban settings and have become smaller.

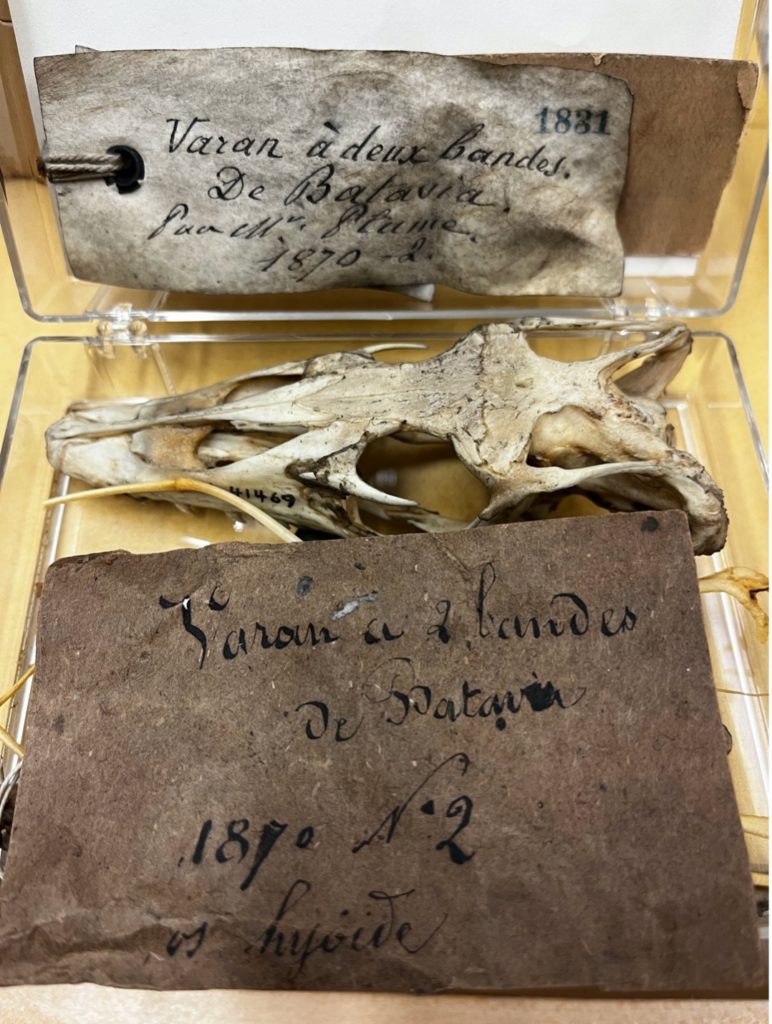

“There is a gap in the literature,” says Dr. Sheridan. “Given that climate change and urbanization are projected to continue their rapid growth, there is an urgency to understanding how their respective effects may be working in concert. Specimens from museum collections are a unique data source that can shed light on changes in size with respect to climate and land use changes over time.”

Sheridan and Martin recommend several steps researchers can take to better understand biodiversity loss and ultimately work toward species conservation. These include expanding the taxonomic and geographic scope of research–including the use of museum collections; increasing the use of quantitative data—such as impervious surface area–over categorical data such as urban versus rural zones; and increasing the testing of climate change and land use interactions. Better understanding of the combined effects of climate change and urbanization is imperative for responding to rapid environmental change.