by Patty Dineen

The beautiful wildlife dioramas on the second floor of Carnegie Museum of Natural History have been fascinating visitors for decades. Within the Hall of North American Wildlife, most of these realistic displays feature taxidermy mounts of one or more of the continent’s large charismatic mammals, posed in recreated three-dimensional scenes of appropriate habitat that also feature smaller mammals, birds, insects, and, of course, plants.

Typically, the dioramas don’t display a generic environment, such as say, the Arctic, the mountains, or the desert, but rather, they depict specific places in North America. The key to the “where” of each diorama is the painted background. Most of the wildlife dioramas feature gorgeous and detailed renderings of specific locations in North America such as Kodiak Island in Alaska, the Laurel Highlands of Western Pennsylvania, or the beautiful Hayden Valley in Yellowstone National Park.

Finding the Locations That Inspired the Dioramas

Is it still possible to travel to, and view, the locations featured in these wonderful dioramas? Would those places look the same today as when they inspired artistic rendering as wildlife diorama paintings many decades ago? And first things first, how would you even go about finding the exact locations depicted in any of the dioramas? Let me tell you a brief story of a recent travel adventure that included an attempt to find the specific vantage point in Yellowstone National Park where a view of the park’s namesake river valley was long ago recreated as a painting some 1,700 miles east in Pittsburgh. The diorama in question features four American elk: two males fighting as two females watch the action from the side. The scene is a snapshot of the fall elk rut, the mating season when males compete to gather “harems” of females.

Last fall, as some museum staff made plans for a guided visit to the park, an attempt to locate and stand in the elk diorama vantage point earned a spot on our agenda.

In early October 2021, our group of 21, consisting of museum staff and their travelling companions, flew from Pittsburgh to Bozeman, Montana, and then traveled south by bus through Paradise Valley to Mammoth Hot Springs in Yellowstone National Park. From this location we began three full days of guided exploration of different parts of the 3,472 square mile park, hoping that at some point we might be able to find the “Elk Diorama” location. We were armed with the Elk Diorama label copy – “…a ritualistic bout between bull elk on the edge of the Hayden Valley, overlooking the Yellowstone River, in Yellowstone National Park,” maps of the park, and photos of the museum’s Elk Diorama. When we shared our information and diorama photos with our two professional guides, one recognized the view and said she was pretty sure she knew the location.

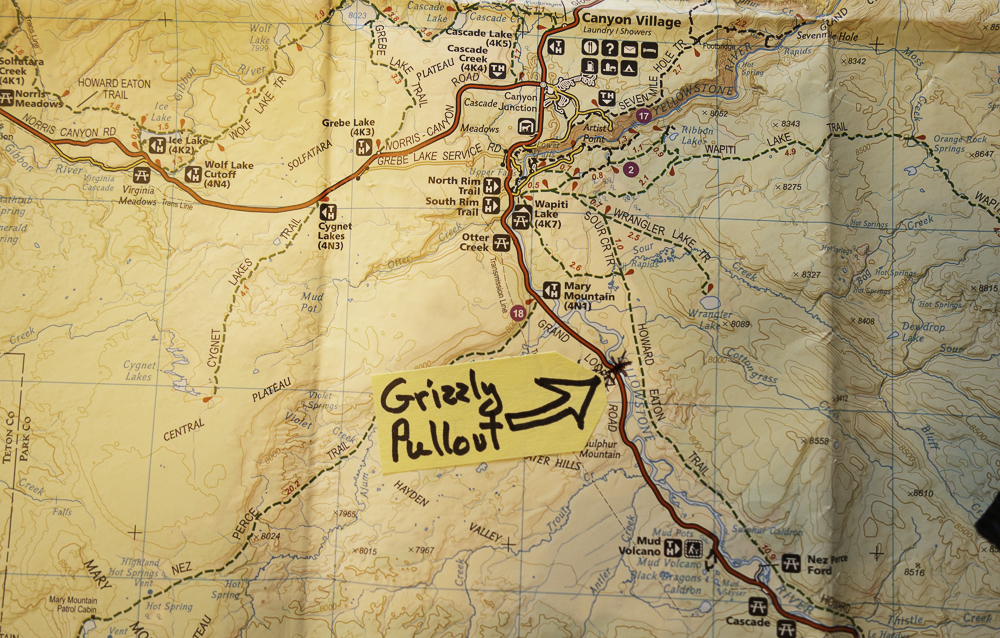

Over our three days of exploring the park we saw geysers and other geothermal features; learned about the Yellowstone National Park wolf project and watched wolves through spotting scopes; and enjoyed wildlife sightings of trumpeter swans, black and grizzly bears, elk, pronghorn, bison, ravens, and young cutthroat trout. On the third and final day, we traveled to The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and Yellowstone Lake, and then headed back north from Fishing Bridge and into the Hayden Valley. And there it was — not marked on my large map but referred to by our guides as “Grizzly Pullout” — a wide spot at the side of the road where a couple of cars or a small shuttle bus could pull over for a view of the Yellowstone River as it begins a graceful bend away from the Grand Loop Road. There was the distinctive (even on this heavily clouded day) profile of distant mountains to the left and middle, and a hillside sloping up and to the right in the middle distance. Group members took photos and enjoyed what seemed a familiar landscape (many thanks to Suzanne and Andy McLaren for the photos they took at Grizzly Pullout). We then headed back to Mammoth Hot Springs for one last night in the park before heading back to Pittsburgh, the museum, and our beautiful wildlife dioramas.

Patty Dineen is a Natural History Interpreter at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Chasing Snails in the Great Smoky Mountains

Doubly Dead: Taxidermy Challenges in Museum Dioramas

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Dineen, PattyPublication date: June 3, 2022