Why did a wealthy European baron seek out a Dakota Territories fossil dealer in the winter of 1889? This post is the first of a four-part series on renowned 19th century fossil collectors Baron de Bayet of Brussels and Lucien W. Stilwell, and their connection to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Bayet assembled one of the great private fossil collections in Europe. In 1903, Andrew Carnegie bought the 130,000-fossil collection and had it shipped from the Port of Antwerp in Belgium across the Atlantic to the United States. The purchase garnered headlines in newspapers across Europe and in the United States and launched Carnegie’s fledgling museum onto the world stage. Thanks to the archival materials purchased by Carnegie as part of the Bayet deal, the relationship between Baron de Bayet and Lucien W. Stilwell provides a glimpse into how the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and other institutions built their collections. In part one, we consider what forces may have prompted Bayet to assemble a large collection of fossils in the first place.

The Pathway to Fossil Collecting Travelled Through the Principles of Stratigraphy and Geology

From the late 17th century until the early 19th century, collecting fossils was a hobby of gentlemen farmers and naturalists. Some of these collectors developed fundamental principles of geology and stratigraphy through observations and deductive reasoning, as to how rock layers, or strata, are formed, fully earning credentials as scientists. For example, in the 17th century physician Nicolaus Steno’s (1638 – 1686) observed simple patterns in strata during his walks through the hills of northern Italy. The four Laws of Stratigraphy he proposed are the law of superposition, the law of original horizontality, the law of cross-cutting relationships, and the law of lateral continuity.

The principles of stratigraphy were later interpreted by James Hutton (1726-1797), a Scottish geologist, to formulate his Doctrine of Uniformitarianism in 1785. This line of thinking assumed that the same natural laws and processes that currently operate in the universe had always operated in the universe and applied everywhere in the universe. Hutton’s Uniformitarianism included the gradualistic concept that “the present is the key to the past”.

William ‘strata’ Smith (1769 – 1835), considered the Father of Stratigraphy was a geologist and engineer who uncovered fossils from strata as he worked to build a water canal from Oxfordshire, England to the Thames River at London. In 1815 he made the first color geologic map of England, Wales, and part of Scotland, a document that developed from his identification of strata based on fossil taxa within the rock layers. His careful tracking suggested that fossil organisms, both faunas and floras, recorded in each geologic formation succeed one another in a definite and recognizable order, a principle summarized as the law of faunal succession.

Smith’s map led, in 1822, to geologists William Conybeare and William Phillips naming the Carboniferous Period for the younger (coal beds) and older (limestones) boundaries respectively for this ancient unit of geologic time. Because a single time period could not rest alone in any record of Earth history, the pioneering work of Conybeare and Phillips, Smith, Hutton, and Steno led eventually to the establishment of the Geologic Time Scale, a framework of three unimaginably long Eras, the Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic, for studying the evolution of life as preserved in the fossil and rock record over Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history. Within the Geologic Time Scale the Carboniferous Period is one of seven periods of the 290 million years that represent the Paleozoic Era.

As these principles of geology grew in acceptances, Charles Lyell (1769 -1875) an English field geologist who traveled extensively throughout Europe and North America, wrote a three-volume Principles of Geology (1830 – 1833), a work that Charles Darwin read during his Voyage of the Beagle (1831 – 1836). Darwin’s Theory of Evolution as written in his The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection – or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life circa 1859, was influenced by the geology and stratigraphy ideas put forth in the Principles of Geology.

Museums Emerged

Amateur fossil collectors such as Stilwell and Bayet perhaps recognized opportunities to supply and acquire fossils to satisfy demand for fossils by museums and universities across Europe and the United States. The first museum to become established in Europe was the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle in Paris, France in 1793, followed by the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin in 1810. Museums in Belgium, London and Austria followed.

In the United States, the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804 – 1806), mandated by President Thomas Jefferson, was the first U.S. government expedition to explore the unknown territory of the Louisiana Purchase in search of minerals, fossils, and indigenous artifacts. Co-led by Merriweather Lewis (1774 – 1809) and William Clark (1770 – 1838), the expedition collections were deposited at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, now known as the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University. Soon, other university museums came into existence such as “The Louis Agassiz Museum of Comparative Zoology”, of Harvard University in 1859, and the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University in 1866. The United States government established the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in 1866. Before long, private institutions such as the American Natural History Museum in New York City, the Field Museum of Chicago, and Carnegie Museum appeared on the scene.

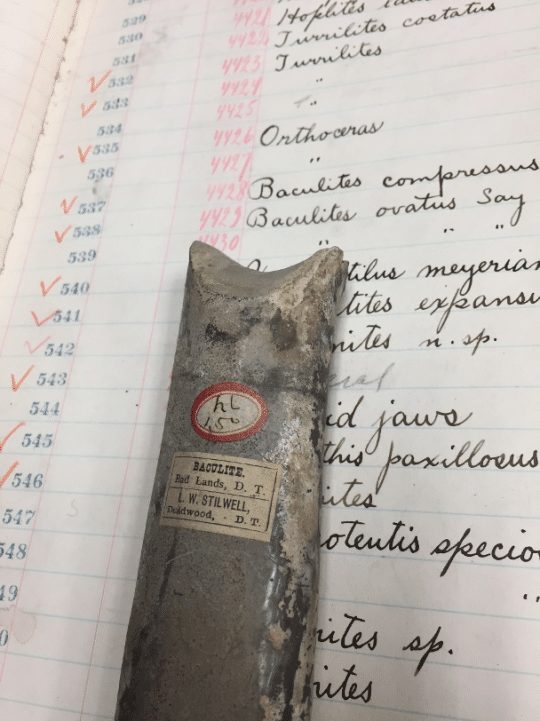

As museums hired scientific staff, rivalries between experts at different institutions developed. By the 1870’s, paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope, of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and O.C. March, of the Peabody Museum at Yale University, began a two-decade competition to outdo each other in a battle to collect and name as many vertebrate fossils as possible. Their exploits are often referred to as “the Bone Wars” (Rea 2001). In 1874, O. C. Marsh arrived in the Dakota Territories. Word of the exotic sea creatures from the Western Interior Seaway and mammals from the Oligocene Period reached Europe, leading the Baron de Bayet to contact Lucien W. Stilwell for his assistance in acquiring “one of every species and variety.”

Next: Lucien W. Stilwell arrives in Deadwood Dakota Territories, a town known for gold, gambling and lawlessness.

Joann Wilson is volunteer with the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology and Albert Kollar is Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.