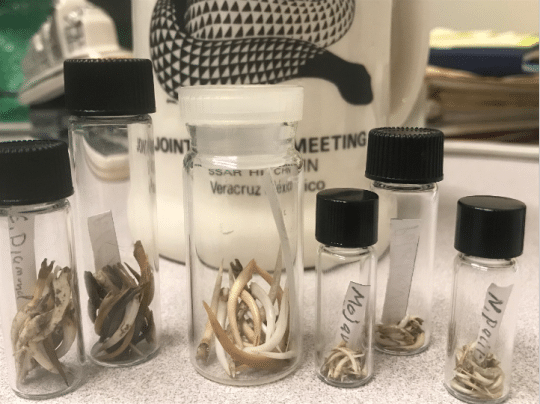

Did you know that bats have been around for at least 55 million years? In 1992, several fossils in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History collection, including the lower jaw bone shown above, were described as representing a new genus and species of ancient bat, Honrovits tsuwape—Shoshone for “bat” and “ghost,” respectively—by a team that included two former curators in the museum’s Section of Vertebrate Paleontology, Christopher Beard and Leonard Krishtalka, both now of the University of Kansas. Honrovits dates to the early part of the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era (the ‘Age of Mammals’), about 50 million years ago, and is a member of a now-extinct bat group called the Onychonycteridae.

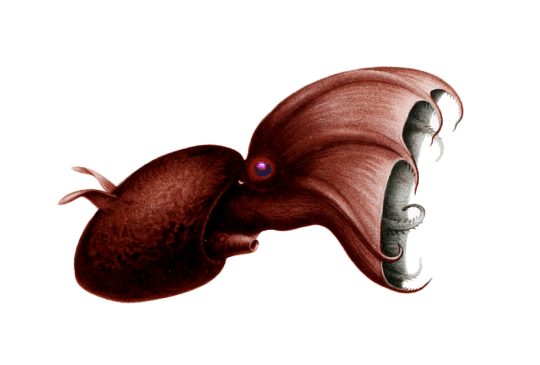

Interestingly, Honrovits shares dental characteristics with a mammal group known as insectivores, which includes today’s hedgehogs, shrews, and moles, and in that sense, it differs from the condition in most other bats. However, bat teeth possess distinctive diagnostic features, so although Honrovits is known only from a few tooth-bearing jaw bones and a skull fragment, there’s no doubt that the diminutive beast was indeed an early bat. The fragmentary nature of its fossils means that we don’t know for sure what Honrovits looked like in life, though it’s a good bet that it bore a close resemblance to other onychonycterid bats, such as Onychonycteris finneyi, which is known from exquisitely preserved skeletons (such as the one shown above).

The incompleteness of the Honrovits fossils is, unfortunately, the norm rather than the exception when it comes to prehistoric bats. Fossils of these creatures are exceedingly rare because most bats have very small, light skeletons and achieve their greatest diversity and abundance in areas that have low potential for fossil preservation, such as tropical forests. Occasionally, complete skeletons such as those of Onychonycteris are found, but not nearly as often as fragments.

So, this autumn, if you happen to catch a glimpse of a bat silhouetted against the evening sky, acrobatically wheeling and plunging in pursuit of flying insects, pause and reflect on the history of these extraordinary flying mammals whose ancestry dates nearly to the time of the dinosaurs.

Linsly Church is a Curatorial Assistant in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

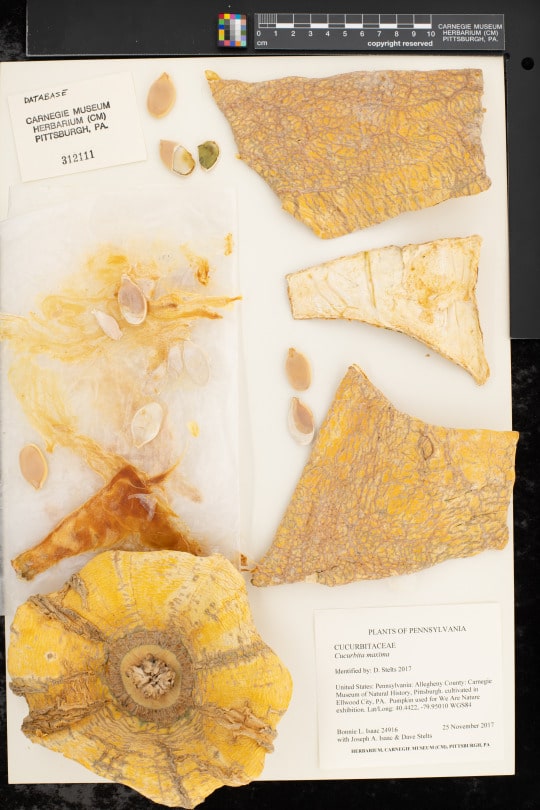

How Do You Preserve a Giant Pumpkin?

Ask a Scientist: What is the newly discovered “Crazy Beast?”